Laboratory-grown replacement organs are the future; since they will be grown from a patient's own cells, there will be no need for immuno-suppressive drugs, and it will eliminate the need for organ donors and waiting lists.

Toward that goal, scientists have grown a fully functional organ from transplanted laboratory-created cells in a living animal for the first time; a thymus, the organ next to the heart that produces immune cells known as T cells that are vital for guarding against disease.

The team from the MRC Centre for Regenerative Medicine at the University of Edinburgh took cells called fibroblasts from a mouse embryo. They turned the fibroblasts into a completely different type of cell called thymus cells, using a technique called reprogramming. The reprogrammed cells changed shape to look like thymus cells and were also capable of supporting development of T cells in the lab – a specialised function that only thymus cells can perform.

Scientists have grown a fully functional organ from transplanted laboratory-created cells in a living animal for the first time. They grew a working thymus -- an important organ that supplies the body with immune cells.

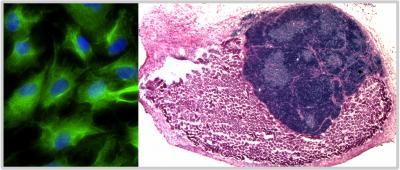

Left: Specialized thymus cells were created in the lab from a completely different cell type using a technique called reprogramming.

Right: The laboratory-created cells were transplanted onto a mouse kidney to form an organized and functional mini-thymus in a living animal. Credit: MRC Centre for Regenerative Medicine, University of Edinburgh

When the researchers mixed reprogrammed cells with other key thymus cell types and transplanted them into a mouse, the cells formed a replacement organ. The new organ had the same structure, complexity and function as a healthy adult thymus.

It is the first time that scientists have made an entire living organ from cells that were created outside of the body by reprogramming.

Doctors have already shown that patients with thymus disorders can be treated with infusions of extra immune cells or transplantation of a thymus organ soon after birth. The problem is that both are limited by a lack of donors and problems matching tissue to the recipient.

With further refinement, the researchers hope that their lab-grown cells could form the basis of a thymus transplant treatment for people with a weakened immune system.

The technique may also offer a way of making patient-matched T cells in the laboratory that could be used in cell therapies.

Such treatments could benefit bone marrow transplant patients, by helping speed up the rate at which they rebuild their immune system after transplant.

The discovery offers hope to babies born with genetic conditions that prevent the thymus from developing properly. Older people could also be helped as the thymus is the first organ to deteriorate with age.

The study is published today in the journal Nature Cell Biology.

Professor Clare Blackburn from the MRC Centre for Regenerative Medicine at the University of Edinburgh, who led the research, said: "Our research represents an important step towards the goal of generating a clinically useful artificial thymus in the lab."

Dr Rob Buckle, Head of Regenerative Medicine at the MRC, said: "This is an exciting study but much more work will be needed before this process can be reproduced in a safe and tightly controlled way suitable for use in humans."

Comments