It's about 75 million years younger than the age other scientists have estimated the oldest millipede to be using a technique known as molecular clock dating, which is based on DNA's mutation rate. Other research using fossil dating found that the oldest fossil of a land-dwelling, stemmed plant (also from Scotland) is 425 million years old and 75 million years younger than molecular clock estimates.

Although it's certainly possible there are older fossils of both bugs and plants, they haven't been found -- even in deposits known for preserving delicate fossils from this era -- which could indicate that the ancient millipede and plant fossils that have already been discovered are the oldest specimens. Fossilization is bordering on the miraculous anyway and this could easily be the oldest that will ever be found.

If that's the case, it also means both bugs and plants evolved much more rapidly than the timeline indicated by the molecular clock. Bountiful bug deposits have been dated to just 20 million years later than the fossils. And by 40 million years later, there's evidence of thriving forest communities filled with spiders, insects and tall trees. If this holds up, bugs and plants evolved much more rapidly than some scientists believe, going from lake-hugging communities to complex forest ecosystems in just 40 million years.

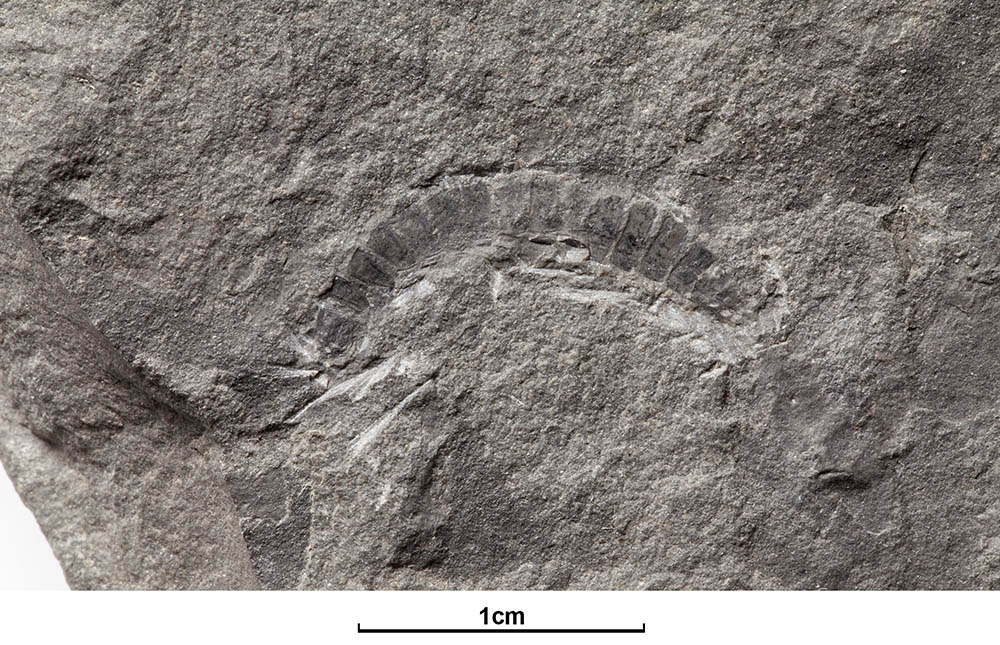

One reason for the delay in addressing the age of the ancient millipedes could be the difficulty of extracting zircons -- a microscopic mineral needed to precisely date the fossils -- from the ashy rock sediment in which the fossil was preserved. As an undergraduate researcher, Stephanie Suarez, a doctoral student at the University of Houston, developed a technique for separating the zircon grain from this type of sediment. It's a process that takes practice to master. The zircons are easily flushed away when trying to loosen their grip on the sediment. And once they are successfully released from the surrounding rock, retrieving the zircons involves an eagle-eyed hunt with a pin glued to the tip of a pencil.

As an undergraduate, Suarez used the technique to find that a different millipede specimen, thought to be the oldest bug specimen at the time, was about 14 million years younger than estimated -- a discovery that stripped it of the title of oldest bug. Using the same technique, this study passes the distinction along to a new specimen.

Comments