Some exoplanets with masses two to four times the size of Earth can be explained by large amounts of water - and they may be more common than previously thought, say researchers.

The 1992 discovery of exoplanets orbiting other stars has sparked interest in understanding the composition of these planets to determine, among other goals, whether they are suitable for the development of life. Now a new evaluation of data from the exoplanet-hunting Kepler Space Telescope and the Gaia mission indicates that many of the known planets may contain as much as 50% water. This is much more than the Earth's 0.02% (by weight) water content.

Water has been implied previously on individual exoplanets, but this work concludes that water-rich planets are common. This bodes well for planet formation of Earth-like planets with water and the search for life beyond our Solar System.

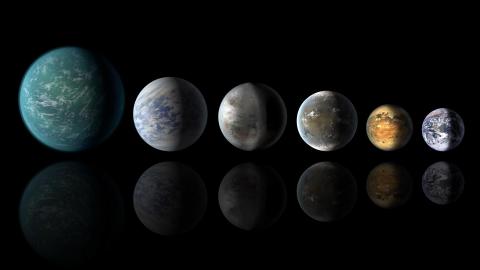

Credit: NASA

Scientists have found that many of the 4,000 confirmed or candidate exoplanets discovered so far fall into two size categories: those with the planetary radius averaging around 1.5 that of the Earth, and those averaging around 2.5 times the radius of the Earth. Now the group analyzing the exoplanets with mass measurements and recent radius measurements from the Gaia satellite have developed a model of their internal structure.

The model indicates that those exoplanets which have a radius of around 1.5X Earth radius tend to be rocky planets (of typically x5 the mass of the Earth), while those with a radius of 2.5X Earth radius (with a mass around x10 that of the Earth) are probably water worlds.

"This is water, but not as commonly found here on Earth", said Dr. Li Zeng of Harvard University. "Their surface temperature is expected to be in the 200 to 500 degree Celsius range. Their surface may be shrouded in a water-vapor-dominated atmosphere, with a liquid water layer underneath. Moving deeper, one would expect to find this water transforms into high-pressure ices before we reaching the solid rocky core. The beauty of the model is that it explains just how composition relates to the known facts about these planets.

"Our data indicate that about 35% of all known exoplanets which are bigger than Earth should be water-rich. These water worlds likely formed in similar ways to the giant planet cores (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune) which we find in our own solar system. The newly-launched TESS mission will find many more of them, with the help of ground-based spectroscopic follow-up. The next generation space telescope, the James Webb Space Telescope*, will hopefully characterize the atmosphere of some of them. This is an exciting time for those interested in these remote worlds."

Comments