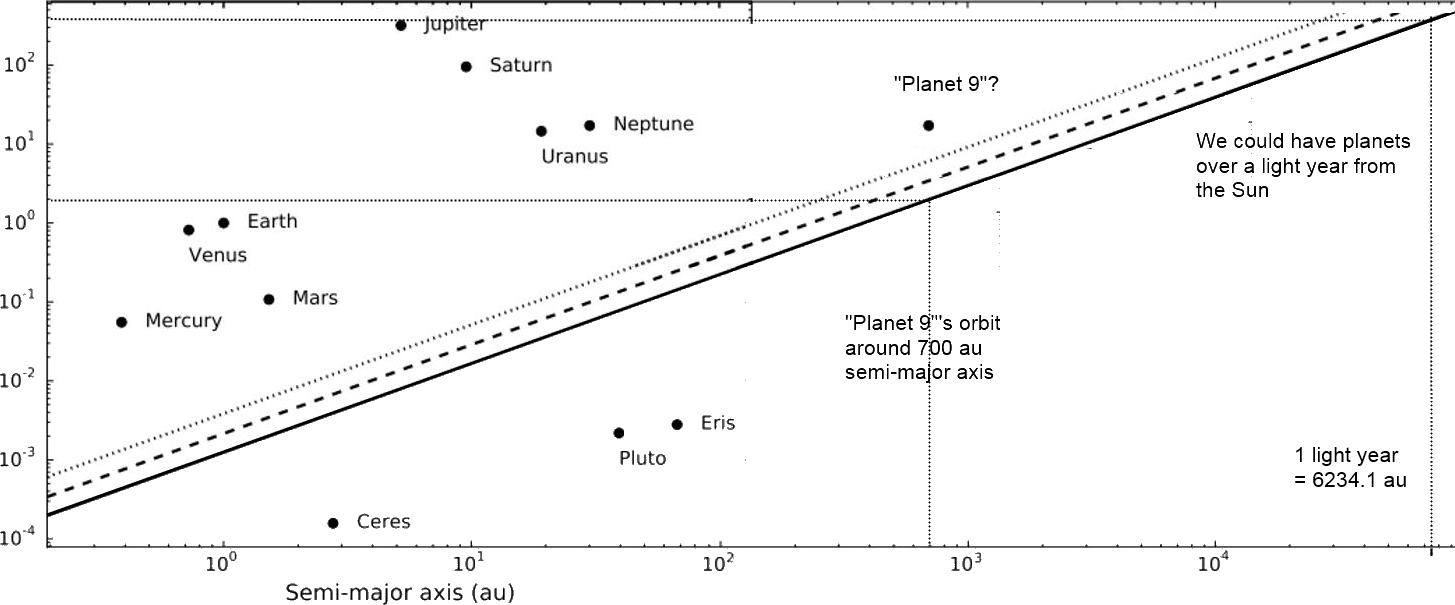

Ethan Siegel has just written an article, "The Science Has Spoken: Pluto Will Never Be A Planet Again", so this is a response to it. I'll argue that far from "story over", actually we could make a discovery tomorrow that would turn the whole thing on its head and make their definition untenable. This will become particularly acute if we ever find a gas giant in the outer reaches of our solar system, too far away to clear its orbit. And we could find such a planet. The WISE survey only ruled out Saturn sized planets out to 10,000 AU and Jupiter sized ones out to 26,000 au. We could have gas giants that orbit our sun over 1.5 light years away, or over 100,000 au. For consistency, we would have to call it a "Gas Giant Dwarf Planet Non Planet". To explain why, first, here is the graph from his article which he uses to show the neat division between large planets that clear their neighbourhood and small ones that don't. But I've extended it to a light year, and let's use Alan Stern's terminology - let's call an orbit clearing planet an "uber planet" and one that doesn't, an "unter planet":

The vertical axis shows its mass in Earth masses. Full size image here.

The three lines here show three possible definitions for the IAU planet, or uber planet. As he points out, there's a clear division between the IAU planets, or "uber planets" as I will call them in this article and the unter planets. The unter planets are all much smaller, and what's more, there are no objects that are anywhere close to the line between the two.

That’s kind of neat for as long as this pattern holds, that all unter planets are much smaller than uber planets. I think it’s already a bit strange to say they are not planets, when they are “dwarf planets”. But there’s more than that.

The diagram already shows that an Earth sized object could be a dwarf planet and not a planet if it was far away as 700 au, the predicted semi-major axis for "Planet Nine" if it exists. Now, it's true that they predict it to be Neptune sized, and at that mass, 17 times the mass of Earth, it would sneak in as a planet. But one hypothesis is that "Planet 9" is not one planet but several planets in resonance, which according to some Spanish astronomers may explain the observations better.

Worlds Beyond Pluto --"There's Not Just Planet 9, But Several Planets Beyond"

In that case they could be of different sizes, and what's to stop some of them from being too small to be IAU planets, yet larger than Earth?

This would hardly be unprecedented. After all when Pluto was discovered, the astronomers were looking for a much larger planet, large enough to perturb the orbit of Neptune, but they just found the tiny Pluto.

I think once we have Earth sized "dwarf planets" that are not planets, if that happens, the definition will already seem a bit awkward. How can an Earth sized object out in the outer solar system be a dwarf planet, and not a planet, when Mercury, Mars and Earth are planets and not dwarf planets?

But it gets worse than that. We could have planets orbiting as far as the proposal for Nemesis, 1.5 light years away, or around 100,000 au. If you continue Ethan Siegel's graph that far then Uranus, Neptune, Saturn, and even Jupiter would be too small to count as planets at that distance

There is plenty of space in the outer solar system to find a planet the size of Saturn which is so far from the Sun that it has no chance of "clearing its orbit". According to the IAU definition it would be a "Gas Giant Dwarf Planet". If we find such a planet, then surely at that point, the definition would have to change. So it is not "Future proof".

We could easily end up with a Saturn sized “dwarf planet gas giant”. Also according to the IAU definition, though a gas giant, it wouldn't be a planet. At that point I think our language about planets is going to seem really messed up. That could happen. It could happen tomorrow that someone discovers a Saturn or Jupiter sized object that orbits our sun too far away to count as a planet.

If it is as massive as Jupiter, it's likely to have a thick hydrogen atmosphere also, like Jupiter, and what else can we call it but a "gas giant"? So then the rest of the name would follow if we use the IAU definition. It would be a “dwarf planet gas giant” and because it doesn't clear its orbit, then also, not a planet.

And what’s the problem with having hundreds of planets? It’s not a problem with asteroids, or stars, that we have too many of them. You can have sub categories of especially interesting ones. The gas giants. The terrestrial planets that orbit close to the sun. Then – dwarf planets – Earth sized and smaller. Sub dwarf planets.

Why not use the word “dwarf” to refer to the size of the planet. The English word has nothing to do with “clearing orbits”. Then have another word for a planet that clears its orbit, and Alan Stern's "uber planet" is as good a name for it as any.

I think language matters, that if we have clear language then we can communicate more easily and think more clearly.

So, the IAU definition is not future proof. I'm pretty sure that if we find a Saturn sized “dwarf planet gas giant non planet” it won’t be long before the IAU definition gets changed and Pluto along with Ceres, and all the other dwarf planets are reinstated as planets. But better to do it now.

If we don't find such planets in our own solar system, we are just about bound to find them in other solar systems once our planet detection techniques are good enough. Gas giant sized planets that are still attached to their parent star, but are so far away from them that they can't "clear their orbits".

COULD WE FIND A GAS GIANT DWARF EXOPLANET IF WE APPLIED THE IAU DEFINITION TO OTHER SOLAR SYSTEMS

Let's use Margot's ? - the various measures are all are in pretty good agreement in the discrimination between planets and non planets - and that's the only one that's easy to calculate. Very easy.

We want a heavy star with the planet far from it, so to find it I sorted the Wikipedia list of exoplanets with the most massive star first.

Here is the formula:

With the planet m measured in Earth masses, M is measured in solar masses, and a in au.. And k for those units is 833. S

The planet masses are often given in Jupiter masses. Jupiter is 317.83 Earth masses, and 833*317.83 =264752. So then the formula is

264752*m / ((M(5/2)*( D (9/8))

m= planet mass in Jupiters, M= star mass in sun masses, D= distance in AU.

One of the best candidates is Fomalhaut b. This one has actually been imaged :). Or at least a cloud or dust around it.

Fomahaut b is in a 2,000 year highly elliptical orbit from these observations by Hubble.

It orbits at a distance of 115 au around a star that has mass at least 1.9 times the mass of the sun. It is probably a planet of mass at most twice that of Jupiter though probably much less. So putting this into the equation:

M =1.9

m = 2

a = 177 ± 68

gives a Margot PI of 543.

It is "shrouded in dust but very plausibly a planet identified from direct imaging"

Artist's impression of Fomalhaut b (courtesy NASA). If it is a gas giant as shown, it will have Margot's PI > 1.

However surely it is just a matter of time before we find a gas giant orbiting far enough from its host star to not be orbit clearing?

Now it could be a much smaller planet as they don't know its size. What could its mass be to give a Margot PI less than 1? Let's use Earth masses:

833*m / ((M(5/2)*( D (9/8)) <1

so m < ((M(5/2)*( D (9/8)) /833 = ((1.95/2*(109 9/8) / 833 = 1.17.

So if the mass of Fomalhaut b is one Earth mass, it could have Margot PI = 833 / ((1.95/2*(109 9/8) = 0.854

According to one theory for Fomalhaut b it may consist of two planets, with the scattered optical light measurements detecting one of them. Both probably both less in mass than three Earth masses, or else one is much more massive than the other. One possibility they discuss is the case where one is a super Earth and the other is a Mars mass planet. If so the smaller Mars mass planet would have Margot's PI < 1. If so it may be a dwarf exoplanet according to the IAU definition.

GEOPHYSICAL DEFINITION

The IAU definition did get one thing right, when they required a planet to be in hydrostatic equilibrium. Here are the two competing definitions:

The IAU's original, 2006 definition:

- It needs to be in hydrostatic equilibrium, or have enough gravity to pull it into an ellipsoidal shape.

- It needs to orbit the Sun and not any other body.

- And it needs to clear its orbit of any planetesimals or planetary competitors.

A planet is a sub-stellar mass body that has never undergone nuclear fusion and that has sufficient self-gravitation to assume a spheroidal shape adequately described by a triaxial ellipsoid regardless of its orbital parameter.

I have just one issue with this proposal the requirement of a triaxial spheroidal shape. All the dwarf planets and planets we know of so far are approximately spheres, oblates spheres, or triaxial ellipsoids (all of which can be described as triaxial spheroids with one or more axis the same length). But that's not necessarily going to continue to be true.

Artist's impression of Haumea spinning. It has this rugby ball shape, not because of tidal effects of its moons, but because it spins so fast. The mathematician Jacobi predicted back in 1834 that sufficiently rapidly spinning planets would e"break symmetry" and become triaxial spheriods instead of oblate spheriods.

As it spins faster, other shapes become the preferred shape:

A rapidly spinning planet eventually becomes a dual lobed "Roche world" then finally three, and then four lobes become favoured, and a sufficiently rapidly spinning planet, just on the verge of breaking apart, is stable as a torus, with a hole in the middle, like a doughnut.

For more on this see my So You Thought You Knew What Spinning Planets Look Like? ... Surprising Shapes Of Rapidly Spinning Planets

I think it’s not impossible that we find contact binary planets out there. After all we know of many contact binary asteroids, such as the striking "peanut shaped" Asteroid 1999 JD6 observed by radar during a flyby of Earth on July 15, 2015

It may be no more than a matter of time before we find the first contact binary planet.

Also, though approximately an oblate sphere, Earth is really rather uneven in shape. It's a geoid. "The geoid is the shape of an imaginary global ocean dictated by gravity in the absence of tides and currents."

Also Earth is distorted just slightly by the tides from the Moon as well, so its shape is continually changing. A double planet, even a non contact binary, with the two planets close together, will no longer be a triaxial spheriod, but more egg shaped, due to the tidal effects.

If you say that the planet has to be self gravitating and in hydrostatic equilibrium, then the details of the shape don't matter.

ISSUES WITH THE NAME "PLANET 9"

Incidentally, I also think “Planet 9" is a bad name because – even if you go by the clearing orbits definition, it might not turn out to be a planet at all if it consists of several dwarf planet non planets. Also, if it is a planet, how do you know it is the ninth?

It’s so far away that there could be another IAU planet closer to the sun than it. We need a better name for it, though I don’t know how this can be accomplished with everyone used to calling it “Planet 9". I call it that too otherwise I’d not be understood.

"Planet X" is not exact enough as it would also apply to Nemesis, Tyche, the idea of an extra planet to explain the Kuiper cliff, and indeed, even to Pluto itself, which was the original Planet X - in the context of a discussion of Lovell's writings if you talked about Planet X you'd mean Pluto, or at least, the object that he hypothesized to exist that lead to Pluto being found.

So, there's no choice, we are stuck with this for now, unless someone comes up with another name that "sticks". But the name is a clumsy one that's also likely to be inaccurate - and since when did we refer to planets by numbers anyway? Earth is not "planet 3" and Mars is not "planet 4".

See also my “Pluto – When Is A Dwarf Planet Not A Planet?”

MIKE BROWN PREDICTION OF A FUTURE DISCOVERY OF A MARS SIZED DWARF PLANET NON PLANET BEYOND NEPTUNE

I've just found a quote from Mike Brown himself giving the same argument I did. He predicts here using a statistical argument from the orbit of Sedna, that we are likely to find planets beyond Neptune that are Mercury, Mars or even Earth sized. He then goes on to say.and goes on to speculate about the future IAU meeting after astronomers find a Mars sized Dwarf Planet Non Planet according to the IAU definition.."I am willing to go out on a limb there and predict, we will find something like that, the size of Mars, in this region of space. And scientifically, this will be fantastic because we will get to learn about an entirely new class of objects, and try to understand how they got there. But just as much fun, of course,is that this will cause the astronomers to go into a tizzy again. Because, if you find it, what do you call it? Well by the current definition - and I forgot to tell you of course, the current definition is, you have the eight planets, and if you are not a planet but you are still one of those round things, you are a dwarf planet.

It's a weird word because there are very few cases in the English language where you have adjective, noun, combination "dwarf planet" is not a "planet". Dwarf planets are not planets. They are dwarf planets. But by the official definition this object the size of Mars would be a dwarf planet. I actually believe that that's the right classification. Because I still think that this population deserves to be put together and the planets are actually special. But I don't think most people are going to buy that. I think if you find something the size of Mars, something the size of Earth, I think most people are going to want to call it a planet, and I think astronomers are going to get the ?? again. Maybe they will have as much fun as they did in Prague."

The video is here:

Comments