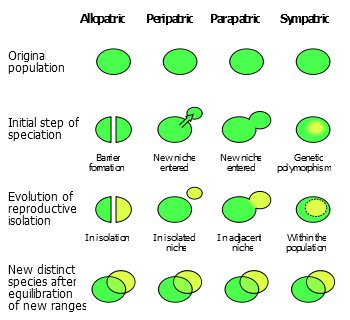

Preconceptions, Evolutionary Strategies And Mosses

Preconceptions, Evolutionary Strategies And MossesIt's hard not to see the world through the lens of our own preconceptions and biases. We tend...

Finding Osama bin Laden with Biogeography

Finding Osama bin Laden with BiogeographyI saw the coolest thing ever on the Rachel Maddow Show tonight. Ever. Thomas Gillespie of the Geography...

The creator, or the content?

The creator, or the content?In my last article, I ended with the observation that:While we cannot reject Cook's scientific...

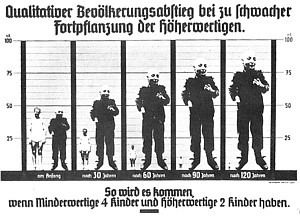

Crazy Ideas And Solid Science: Evolutionary Genetics And Eugenics In The 1920s And 30s

Crazy Ideas And Solid Science: Evolutionary Genetics And Eugenics In The 1920s And 30sRoystonea, the royal palms, are the most striking palms in the Caribbean, and arguably, in the...