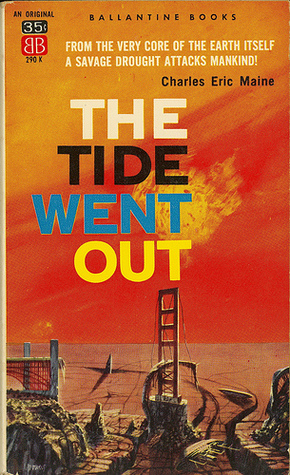

Fans of British apocalypse novels a la Wyndham and John Christopher ought to enjoy Chalres Eric Maine’s The Tide Went Out, another story focused the catastrophic disintegration of British society in the context of a world-wide disaster. Journalist Philip Wade writes a speculative story about the potential adverse geological effects of nuclear testing, and inadvertently almost reveals a tightly held state secret. The recent nuclear tests of ‘Operation Nutcracker’ have busted open the earth’s crust, and the oceans are draining away into the earth’s interior. Wade has his story pulled at the last minute by mysterious government officials. But oddities offer clues: frequent earthquakes trouble seismically mild Britain, and the tide steadily decreases. Soon shipping is impossible, and Britain (and the rest of the world) goes into crisis as the world dries out - no clouds, no rain, no crops, etc..

Fans of British apocalypse novels a la Wyndham and John Christopher ought to enjoy Chalres Eric Maine’s The Tide Went Out, another story focused the catastrophic disintegration of British society in the context of a world-wide disaster. Journalist Philip Wade writes a speculative story about the potential adverse geological effects of nuclear testing, and inadvertently almost reveals a tightly held state secret. The recent nuclear tests of ‘Operation Nutcracker’ have busted open the earth’s crust, and the oceans are draining away into the earth’s interior. Wade has his story pulled at the last minute by mysterious government officials. But oddities offer clues: frequent earthquakes trouble seismically mild Britain, and the tide steadily decreases. Soon shipping is impossible, and Britain (and the rest of the world) goes into crisis as the world dries out - no clouds, no rain, no crops, etc..As in No Blade of Grass, the British government has a secret plan that does not benefit most of its citizens - secret Arctic camps are built to hold privileged evacuees, while the government sets up a powerful security and propaganda machine to keep the populace pacified. Wade lands a plum job with the propaganda department while his family is shipped to the Arctic, but the government smokescreen of course proves increasingly difficult to maintain as the situation becomes more dire, and civil unrest breaks out. Wade develops from government tool into a desperate survivalist, ready to kill to make it back to his family.

The style of The Tide Went Out is a little pulpier than The Day of the Triffids, Kraken Wakes and No Blade of Grass, but the well-plotted story hits all of the main features of classic 1950’s British apocalypse stories. Nobody wants to acknowledge the looming disaster, and then when it can’t be ignored, there are desperate hopes that science will come up with a last minute miracle. As the disaster grows, the British government develops plans to contain its doomed citizens, while a well-connected few make it out. The protagonist somehow gets an inside scoop and manages to keep one step ahead as violence inevitably breaks out. And there is always one person in the classic role of the philosopher of the apocalypse, who goes on, frequently at great length, about how the catastrophe simply unmasks nature as it has always been:

“Things are strictly under control. Not in the nicest way, perhaps - but under control. You have to remember that some seventy per cent of the population of this planet are going to die anyway - in the very near future. That changes the moral climate of society. Death is, in a sense, a public service. Even nature realizes that. Have you ever thought, Wade, that when mass death is desirable, nature often takes a hand in the proceedings.”

“You mean such things as typhoid and cholera?”

“Exactly.”

“I wouldn’t blame nature, Major. After all, nature didn’t manufacture the H-bomb that split the bed of the Pacific Ocean.”

Cary laughed and puffed smoke rings. “Nature manufactured Homo sapiens, and Homo sapiens manufactured the H-bomb and destroyed the world. The chain of responsibility is direct enough.”

The idea of nature taking a hand in mass death when it becomes necessary hearkens back to major themes in Triffids and Earth Abides. In this case, human extinction by H-bombs isn’t fundamentally any different from extinction by other means - extinction is what happens in nature.

The idea of nature taking a hand in mass death when it becomes necessary hearkens back to major themes in Triffids and Earth Abides. In this case, human extinction by H-bombs isn’t fundamentally any different from extinction by other means - extinction is what happens in nature.That doesn’t mean that the characters of The Tide Went Out are fatalists. They realize that the game of survival has shifted. For centuries (if not millennia), humans have managed to adapt the environment to their own needs through science and technology. In a post-apocalyptic world, that is no longer possible, and those who are to survive will now have to adapt themselves to an uncontrollable environment, just as our ancestors did eons ago, before technology gave them the ability to change their environment.

In this context, Wade gradually morphs into a survivalist. It begins with his temptation to cheat on his wife, yet again. In the past, he almost destroyed his marriage, but has managed to hold it together until the disaster begins. Once Wade’s family gets shipped off to the arctic (there is some hint that Mrs. Wade’s family connections got Wade his government job, and his family’s ticket to safety) and as societal restraints gradually loosen, Wade feels free to fall in love again, with a coworker. As the strain of the dying world builds, the two lovers get restless awaiting evacuation in their highly defended bubble that has isolated them from the horrors on the London streets. A tragic accident lands Wade on the streets, where he sees the human tragedy occurring first hand. After that, the only thing that matters to Wade is survival, which means escaping to the Arctic, and he is willing to do anything to get there.

Although not as elegantly written as the disaster novels of Wyndham and Christopher, The Tide Went Out is a great story featuring classic post-apocalyptic themes of nature’s hostility and the de-repression of humanity’s brutal survival instinct.

Postscript: Also published in 1958 (and proudly advertised on the back cover of The Tide Went Out) is John Bowen’s abysmal After The Rain, a badly written modern take on Noah’s ark. It’s a satire about humanity brought down by its arrogant attempts to master nature - our species’ suicide is prevented by a catastrophic act of nature. If you liked The Tide Went Out, you might see the ad and be tempted to try After The Rain. Resist the temptation.

Next up in our survey of post-apocalyptic literature, a well-known Cold War classic, the book Tom Clancy would have written if he were writing nuclear holocaust novels in the 1950’s: Pat Frank’s 1959 Alas, Babylon.

Read the feed:

Comments