Saffron

In one of my school history books, as I remember, there is a story that saffron was introduced into Europe by a pilgrim from concealing some corms in his staff, to avoid the death penalty if found by the agents of the Sultans who controlled its export. However, the history of saffron, including a 14-week ‘saffron war’, seems much more complicated that this.

Wasabi ワサビ(山葵)

The story of the pilgrim, however, came to mind when on Sunday, 19 May 2013, the BBC’s Countryfile treated us to a visit to Britain’s only wasabi farm, at a top secret location in the South of England. The reporter was Julia Bradbury, often seen striding over the countryside or up-and-down hills, even that Icelandic volcano. Now, she tells us, she hates mustard and horseradish, so wasabi, often known as ‘Japanese horseradish’, did not sound particularly appealing to her.

The cultivation of wasabi in Japan is very secretive, and relies on spring water ‘full of minerals’ – though whether that expression is technically true or simply poetic I cannot tell. So we saw the farmer and Julia stepping across a bed of gravel, first planted with small seedlings or divisions, then to some larger plants. One of them was ready for harvest.

Then there appeared a chef, ready to prepare the rhizome for eating. The result was a small mound yellowish-green paste, which Ms Bradbury was then cajoled into trying. After some diffidence, she found that she could tolerate its ‘nutty’ flavour. Next to this was a bright green mound of commercial wasabi paste. She tasted that, and immediately spat it out in horror and disgust. The commercial paste, so we were told, only contains 4% wasabi, and most of the rest is horseradish.

But was stealing from Japan? Maybe not, rather the returning of a favour from the 1950s.

Nori 海苔

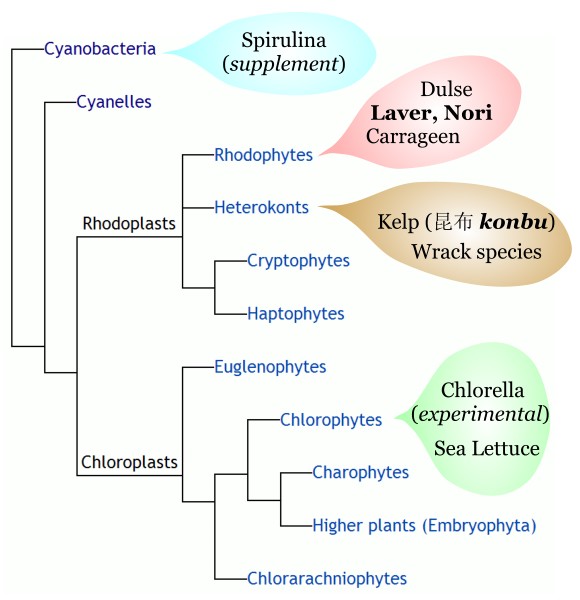

This is the seaweed that one finds wrapped around sushi. Seaweeds are much more varied than I ever thought, and I have listed some of the edible ones on top of the cladogram from Wikipedia below. The edible ones that I have found include Rhodophytes (red algae), Heterokonts (brown algae) and Chlorophytes (green algae which are the nearest to land plants). Spirulina as found in supplements is now not considered an alga at all, since cyanobacteria (free-range chloroplasts, as one lecturer called them many years ago) are no longer called ‘blue-green algae’. I have included konbu, the Japanese name for kelp if you want to search for it in an Oriental supermarket: the Chinese name 海带 hǎidài means ‘sea belt’.

Kathleen Mary Drew-Baker (1901–1957) was a British phycologist, (not psychologist!), particularly known for her basic research on the edible seaweed Porphyra laciniata (nori), which led to a breakthrough for commercial growing. She had studied the edible seaweed Porphyria umbilicalis (laver), working out its reproductive cycle. Here is a diagram, relabelled from a figure in Nonvascular plants: an evolutionary survey, by R.F. Scagel et al, 1982 (hat tip: http://comenius.susqu.edu/biol/202/archaeplastida/rhodoplantae/rhodophyta/). The plant shows alternation of generations: The haploid (one set of chromosomes) thallus at A gives rise to male spores B which find the female ova C and produce diploid (paired chromosome) fertilized cells D which develop as in E – H; meiosis (paired sets of chromosomes separating) gives another kind of spore (I) which develops into the haploid thallus (J – K – A).

According to an article from the Manchester Museum of Science&Industry:

Seaweed farming in Japan can be traced back many centuries. Throughout its history, nori has been part of the staple diet of the Japanese at times of good harvest, regarded as a luxury item when harvest were poor and used as a medicine. It is rich in minerals such as calcium, iron and iodine, and is reputed to be good for the skin and hair. Nori grows in shallow water on rocks, shells and branches of trees. The nori seaweed grows from October until February and by June it completely disappears. Prior to the publication of Dr Drew-Baker’s research, harvests of nori would fluctuate wildly from year to year and, as a consequence, it became known as gamblers’ grass.

In 1948, disaster struck the Japanese nori farming industry. The increased use of fertilisers on Japanese farms and the increase in industrial pollution in coastal waters, combined with a series of typhoons, destroyed many of the seaweed beds and led to very poor harvests. Many farmers lost their livelihoods and as a result were left with nothing. Japanese scientists were unable to offer any practical help, as little was known about the life cycle of the nori seaweed.

Each year on 14 April, people involved in the lava farming industry gather at Sumiyoshi Shrine Park to celebrate the Drew Festival. The memorial refers to Dr Drew-Baker as ‘the Mother of the Sea’.

A major factor in what was going wrong is that the fertilized cells D need a mollusc shell to settle on and proceed to H and I. So Drew-Baker’s work certainly provided the technical solution to the problem. However, The story of the Seaweed Lady in The Nut Graph !? also points to a sociological reason for the disaster. This article puts the blame for the 1948 crash on the depletion of the farmers who were conscripted into the Japanese army, losing the practice of providing the nori beds with an adequate supply of mollusc shells, from which boring organisms generated particles for the spores to settle on.

(note: 海苔 the Kanji for nori mean something like ‘sea liverwort’)

And to finish, back to a lovely Japanese illustration of the Wasabi plant from 1828:

Comments