British astronomers from the University of Cambridge and the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) have developed a new camera that gives much more detailed pictures of stars and nebula than even the Hubble Space Telescope, and it does all this from the ground. Images from ground-based telescopes are usually blurred out by the atmosphere.

Astronomers have tried to develop techniques to correct the blurring called adaptive optics but so far they only work successfully in the infrared where the smearing is greatly reduced. However a new noise-free, high-speed camera has been developed at the Institute of Astronomy in Cambridge which makes very high resolution imaging in the visible possible.

The camera works by recording the images produced by an adaptive optics front-end at high speed (20 frames per second or more). Software then checks each one to pick the sharpest ones. Many are still quite significantly smeared but a good percentage are unaffected. These are combined to produce the image that astronomers want. We call the technique "Lucky Imaging" because it depends on the chance fluctuations in the atmosphere sorting themselves out.

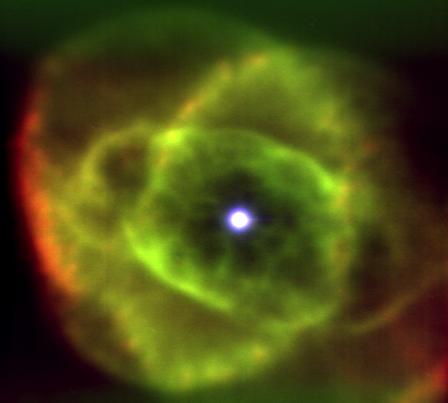

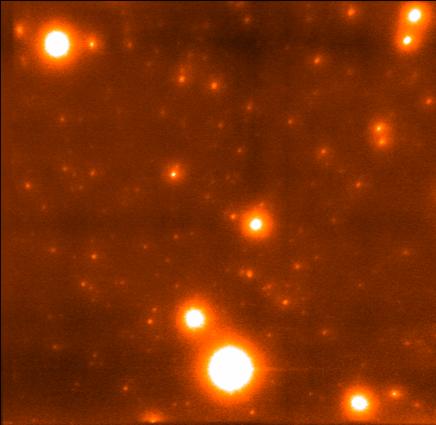

The first images are of NGC6543, the Cat's Eye Nebula and then M13 below. We can see very fine detail in objects such as the Cat's Eye Nebula . It is eight times closer to earth than M13 so we can resolve filaments that are only a few light hours across.

This work was carried out on Mount Palomar with their 200 inch (5.1 m) telescope. Like all other ground-based telescopes, the images it normally produces are typically 10 times less detailed than those of the Hubble Space Telescope. Their adaptive optic system works well in the infrared but up to now gives images in the visible that are still markedly poorer than Hubble images. With the Lucky Camera we obtain images that are twice as sharp as those produced by the Hubble Space Telescope, a remarkable achievement.

These are the sharpest images ever taken in the visible either from the ground or from space. To get sharper pictures you have to use an even bigger telescope.

It opens up the possibility of further improvements on even larger telescopes such as the 8.2 m Very Large Telescope (VLT) of the European Southern Observatory in Chile or the 10 m Keck telescopes on the top of Mauna Kea in Hawaii.

Most astronomical objects are so far away that astronomers are desperate to see more and more detail within them. Lucky Imaging techniques have already enabled the discovery of many multiple star systems which are too close together and too faint to find with any standard telescope. The pictures of the globular star cluster M13 which is at a distance of 25,000 light years are able to find stars as little as one light day apart. The nearest star to earth is over three light years away.

Source: Cambridge

Comments