Light beams travel in straight lines and don't go around corners, they instead spread through a process known as diffraction.

Researchers at Tel Aviv University have discovered that small beams of light can indeed be bent in a laboratory setting, diffracting much less than a "regular" beam. These rays are called "Airy beams" after English astronomer Sir George Biddell Airy, who studied the parabolic trajectories of light in rainbows.

Nonlinear optics is a sub-field of optics that deals with the response of materials to high intensities of light. The strong interaction between light and material results in the generation of new colors, which are half the wavelength of the original input light frequency. For example, a nonlinear response to infrared light can generate visible light ― which is how those bright, green "laser pointers," often used in presentations given in large rooms, generate their light.

Prof. Ady Arie and his graduate students Tal Ellenbogen, Noa Voloch-Bloch, Ayelet Ganany-Padowicz and Ido Dolev of Tel Aviv University's Faculty of Engineering have demonstrated new ways to generate and control Airy beams, employing new algorithms and special nonlinear optical crystals. Their research is reported in a recent issue of Nature Photonics.

Some of these new applications, such as a light source to generate beams that can turn around corners, or lighted spaces that contain no apparent light source, are still five or ten years away, says Arie.

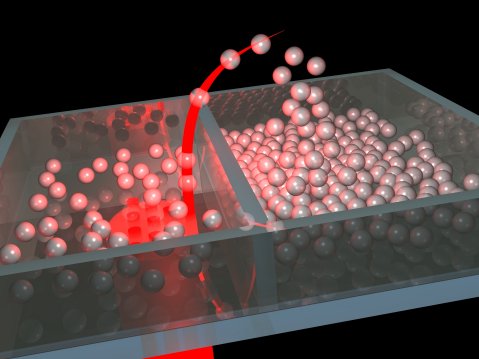

Airy beams. Credit: University of St Andrews

But the research has immediate applications as well. For example, because small particles are attracted to the highest intensities of a beam, the pharmaceutical and chemical industries can use the new beam to sort molecules according to size or quality, filtering impurities from drug formulations that might otherwise lead to toxicity and death.

Until now, reports an editorial review in the publication, Airy beams have been generated through "linear diffraction" using tools that project a single color of light through glass plates of varying thicknesses. But using crystals they built in the lab, Tel Aviv University's approach uses another technique: nonlinear optics. Sent through crystals, light waves bounce inside the crystal, changing their wavelength and color. It is through this process, the researchers say, that the door is opened for creating new light beams at new wavelengths with greater control of their trajectories.

"We've found a way to control whether an Airy beam curves to the left or to the right, for example," says Prof. Arie. He has also found a way to control the peak intensity location of the beams, which are generated through a nonlinear optical process.

Airy beams promise remarkable advances for engineering. They could form the technology behind space-age "light bullets" –– as effective and precise defense technologies for police and the military, but also as a new communications interface between transponders. As tiny, tight packets of information, these Airy beams could be used out in the open air, researchers hope.

Comments