The gene, called Boule, is responsible for sperm production and they say that Boule appears to be the only gene known to be exclusively required for sperm production from an insect to a mammal.

"This is the first clear evidence that suggests our ability to produce sperm is very ancient, probably originating at the dawn of animal evolution 600 million years ago," said Eugene Xu, assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Feinberg. "This finding suggests that all animal sperm production likely comes from a common prototype."

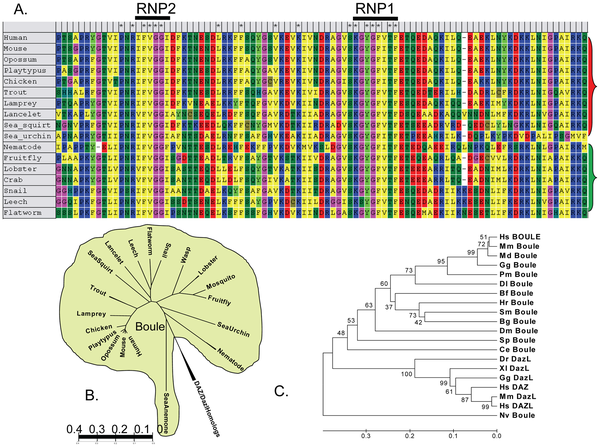

Conservation and prevalence of Boule proteins among animals. (A) Alignment of Boule RRM domains from representative species of both deuterostomes and protostomes reveals conservation of the RNA binding domain, in particular in the regions surrounding RNP2 and RNP1 as well as the C-terminal region. Asterisks (*) mark amino acids conserved in Boule homologs from all species. The red bracket on the right indicates deuterostomian species and the green bracket protostomian species. Colors for individual amino acids are assigned based on similar properties of residues (Table S5). (B) Phylogenetic treatment of homologs from major metazoan branches of human DAZ gene family members (BOULE, DAZL and DAZ) using conserved RRM domains. Consistent with being the most ancient member of the DAZ family, the Boule clade is much more widespread and divergent, including members of the major phyla of protostomes and deuterostomes, while all DAZ/DAZL homologs are clustered together in one branch. The Dazl homolog clad and DAZ clad are much smaller and are restricted to vertebrates or primates, respectively. (C) Rooted tree showing the evolutionary distance among different homologs of the DAZ family. The numbers indicate bootstrap values. The evolutionary tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in units representing the number of amino acids substituted per site. Hs-Homo sapiens, Mm-Mus musculus, Md-Monodelphis domestica, Gg-Gallus gallus, Pm-Petromyzon marinus, Dl-Dicentrarchus labrax, Bf-Branchiostoma floridae, Hr-Helobdella robusta, Sm-Schistosoma mansoni, Bg-Biomphalaria glabrata, Dm-D. melanogaster, Sp-Strongylocentrotus purpuratus, Ce-C. elegans, Dr-Danio rerio, Xl-Xenopus laevis, Nv-Nematostella vectensis. From Widespread Presence of Human BOULE Homologs among Animals and Conservation of Their Ancient Reproductive Function

The discovery of Boule's key role in perpetuating animal species offers a better understanding of male infertility, a potential target for a male contraceptive drug and a new direction for future development of pesticides or medicine against infectious parasites or carriers of germs.

"Our findings also show that humans, despite how complex we are, across the evolutionary lines all the way to flies, which are very simple, still have one fundamental element that's shared," Xu said.

"It's really surprising because sperm production gets pounded by natural selection," he said. "It tends to change due to strong selective pressures for sperm-specific genes to evolve. There is extra pressure to be a super male to improve reproductive success. This is the one sex-specific element that didn't change across species. This must be so important that it can't change."

Boule is likely the oldest human sperm-specific gene ever discovered, Xu said. He originally discovered the human gene in 2001.

Prior to the new findings, it was not known whether sperm produced by various animal species came from the same prototype. Birds and insects both fly, for example, but the fly wing and bird wing originated completely independently.

For the study, Xu searched for and discovered the presence of the Boule gene in sperm across different evolutionary lines: human, mammal, fish, insect, worm and marine invertebrate.

In order to search for Boule's presence across the spectrum of evolutionary development, Xu had an interesting shopping list. He needed sperm from a sea urchin, a rooster, a fruit fly, a human and a fish. The fish proved to be the most difficult.

Xu purchased a rainbow trout at a Chicago fish market, unwrapped it and was dismayed to discover it had been gutted. "I need the testicles!" he exclaimed to the seafood salesman. Xu decided he'd have to catch his own. He cast a fishing line into a recreational pond stocked with trout and reeled in a rainbow trout.

Discovery of this common gene involved in sperm production could have many practical uses for human health, including male contraception. When Xu's research group knocked out the Boule gene from a mouse, the animal appeared to be healthy but did not produce sperm.

"A sperm-specific gene like Boule is an ideal target for a male contraceptive drug," Xu noted.

Boule also has the potential to reduce diseases caused by mosquitoes and parasites such as worms.

"We now have one strong candidate to target for controlling their breeding," Xu said. "Our work suggests that disrupting the function of Boule in animals most likely will disrupt their breeding and put the threatening parasites or germs under control. This could represent a new direction in our future development of pesticides or medicine against infectious parasites or carriers of germs."

To further support his hypothesis that Boule is widespread across all animals producing sperm and eggs, Xu also examined the genome of one of the most primitive animals, a sea anemone, for the presence of Boule. He looked at its genome because the sperm of the sea anemone is difficult to find and few labs study the animal. When Xu identified Boule in the sea anemone genome, his theory was clinched.

Citation: Shah C, VanGompel MJW, Naeem V, Chen Y, Lee T, et al. (2010) Widespread Presence of Human BOULE Homologs among Animals and Conservation of Their Ancient Reproductive Function. PLoS Genet 6(7): e1001022. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001022

Comments