Carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) was once used in dry cleaning and as a fire-extinguishing agent but once it was found to be a cause of ozone depleted, it was regulated in 1987 under the Montreal Protocol along with other chlorofluorocarbons. Parties to the Montreal Protocol have reported zero new CCl4 emissions since, though worldwide emissions of CCl4 still average 39 kilotons per year, about 30 percent of emissions prior to the treaty going into effect.

"We are not supposed to be seeing this at all," said Qing Liang, an atmospheric scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, and lead author of a new study in the compound. "It is now apparent there are either unidentified industrial leakages, large emissions from contaminated sites, or unknown CCl4 sources."

As of 2008, CCl4 accounted for about 11 percent of chlorine available for ozone depletion, which is not enough to alter the decreasing trend of ozone-depleting substances. Still, scientists and regulators want to know the source of the unexplained emissions. For almost a decade, scientists have debated why the observed levels of CCl4 in the atmosphere have declined slower than expectations, which are based on what is known about how the compound is destroyed by solar radiation and other natural processes.

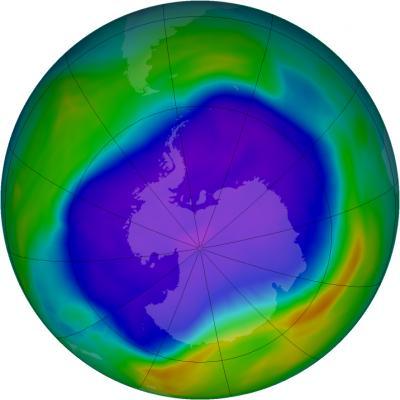

Satellites observed the largest ozone hole over Antarctica in 2006. Purple and blue represent areas of low ozone concentrations in the atmosphere; yellow and red are areas of higher concentrations. Credit: NASA

"Is there a physical CCl4 loss process we don't understand, or are there emission sources that go unreported or are not identified?"

With zero CCl4 emissions reported, atmospheric concentrations of the compound should have declined at an expected rate of 4 percent per year. Observations from the ground showed atmospheric concentrations were only declining by 1 percent per year.

To investigate the discrepancy, Liang and colleagues used NASA's 3-D GEOS Chemistry Climate Model and data from global networks of ground-based observations. The CCl4 measurements used in the study were made by scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA's) Earth System Research Laboratory and NOAA's Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

Model simulations of global atmospheric chemistry and the losses of CCl4 due to interactions with soil and the oceans pointed to an unidentified ongoing current source of CCl4. The results produced the first quantitative estimate of average global CCl4 emissions from 2000-2012.

In addition to unexplained sources of CCl4, the model results showed the chemical stays in the atmosphere 40 percent longer than previously thought.

"People believe the emissions of ozone-depleting substances have stopped because of the Montreal Protocol," said Paul Newman, chief scientist for atmospheres at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, and a co-author of the study. "Unfortunately, there is still a major source of CCl4 out in the world."

Source: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center

Comments