The response to visual threats includes many essential elements of what we humans call fear and David J. Anderson of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the California Institute of Technology and colleagues write in a new paper that their work on fear in flies are a step toward dissecting the fundamental neurochemistry, neuropeptides, and neural circuitry underlying fear and other emotion states.

"No one will argue with you if you claim that flies have four fundamental drives just as humans do: feeding, fighting, fleeing, and mating," says William T. Gibson, a Caltech postdoctoral fellow and first author on the study. "Taking the question a step further--whether flies that flee a stimulus are actually afraid of that stimulus--is much more difficult."

To ask the question in a different and less problematic way, the researchers dissected fear into its fundamental building blocks, which they refer to as "emotion primitives." First, fear is persistent, Gibson explains. If you hear the sound of a gun, the feeling of fear it provokes will continue for a period of time. Fear is also scalable; the more gunshots you hear, the more afraid you'll become. Fear is generalizable across different contexts, but it is also trans-situational. Once you're afraid, you're more likely to respond in fear to other triggers: the clang of a pan, for instance, or a loud knock at the door.

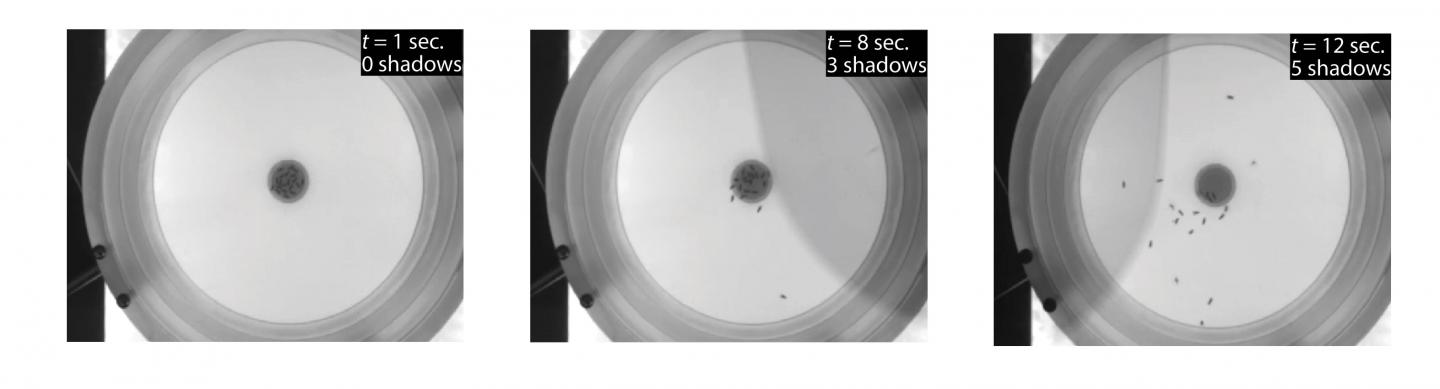

Hungry flies feeding on a food patch show graded responses to a repetitive, overhead shadow stimulus. Moving from left to right, the three images show flies' positions after, respectively, 0, 3, and 5 passes of the shadow stimulus. Credit: William T. Gibson and David J. Anderson

The question then was this: In terms of these building blocks of emotions, does a fly's response to shadows resemble our response to the sound of a gun? Very much so, the new study shows.

Anderson and colleagues came to that conclusion after enclosing flies in an arena where they were exposed repeatedly to an overhead shadow. In collaboration with Pietro Perona's computer vision group, also at Caltech, the team carefully analyzed the flies' behaviors as captured on video, which showed that shadows promoted graded and persistent increases in the flies' speed and hopping. Occasionally, the insects froze in place, a defensive behavior also observed in the fear responses of rodents. The shadows also caused hungry flies to leave a food source, suggesting that the experience was generally negative and generalized from one context to another.

It took time before those flies would return to their food following their dispersal by the shadow, suggesting a slow decay of the insects' internal, defensive state. Importantly, the more shadows the flies were exposed to, the longer it took for them to "calm down" and return to the food.

In other words, when flies flee in response to a shadow, it's more than a momentary escape. It's a lasting physiological state much like fear. And, if that's true, it means that flies could help us understand in a very fundamental way what fear and other emotions are made of.

"The argument that this paper makes is that the Drosophila system may be an excellent model for emotion states due to the relative simplicity of its nervous system, combined simultaneously with the behavioral complexity it exhibits," Gibson says. "Such a simple system, leveraged with the power of neurogenetic screens, may make it possible to identify new molecular players involved in the control of emotion states."

The next step, the researchers say, is to dissect the neural circuitry involved in the flies' shadow response.

Citation: Gibson et al., "Behavioral responses to a repetitive shadow stimulus express a persistent state of defensive arousal in Drosophila" Current Biology DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2015.03.058

Comments