Thanks to a supersensitive space telescope and some sophisticated supercomputing, scientists from the international Planck collaboration have made the closest reading yet of the most ancient story in our universe: the cosmic microwave background (CMB).

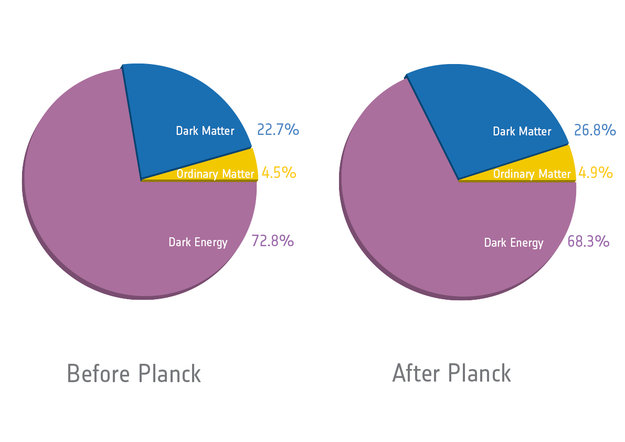

Today, the team released preliminary results based on the Planck observatory's first 15 months of data. They show that the universe is 100 million years older than we thought with more matter and less dark energy.

Decoding the Cosmos

Written in light shortly after the big bang, the CMB is a faint glow that permeates the cosmos. Studying it can help us understand how our universe was born, its nature, composition and eventual fate. "Encoded in its fluctuations are the parameters of all cosmology, numbers that describe the universe in its entirety," says Julian Borrill, a Planck collaborator and cosmologist in the Computational Research Division at Berkeley Lab.

However, CMB surveys are complex and subtle undertakings. Even with the most sophisticated detectors, scientists still need supercomputing to sift the CMB's faint signal out of a noisy universe and decode its meaning.

Parked in an artificial orbit about 800,000 miles away from Earth, Planck's 72 detectors complete a full scan of the sky once every six months or so. Observing at nine different frequencies, Planck gathers about 10,000 samples every second, or a trillion samples in total for the 15 months of data included in this first release. In fact, Planck generates so much data that, unlike earlier CMB experiments, it's impossible to analyze exactly, even with powerful supercomputers.

Instead, CMB scientists employ clever workarounds. Using approximate methods they are able to handle the Planck data volume, but then they need to understand the uncertainties and biases their approximations have left in the results.

One particularly challenging bias comes from the instrument itself. The position and orientation of the observatory in its orbit, the particular shapes and sizes of detectors (these vary) and even the overlap in Planck's scanning pattern affect the data.

To account for such biases and uncertainties, researchers generate a thousand synthetic (or simulated) copies of the Planck data and apply the same analysis to these. Measuring how the approximations affect this simulated data allows the Planck team to account for their impact on the real data.

Hundreds of scientists from around the world study the CMB using supercomputers at NERSC, a DOE user facility based at Berkeley Lab. "NERSC supports the entire international Planck effort," says Borrill. A co-founder of the Computational Cosmology Center (C3) at the lab, Borrill has been developing supercomputing tools for CMB experiments for over a decade. The Planck observatory, a mission of the European Space Agency with significant participation from NASA, is the most challenging yet.

"These maps are proving to be a goldmine containing stunning confirmations and new puzzles," says Martin White, a Planck scientist and physicist with University of California Berkeley and at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab). "This data will form the cornerstone of our cosmological model for decades to come and spur new directions in research."

Comments