Modern seals, sea lions, and walruses all have flippers—limb adaptations for swimming in water. These adaptations evolved over time, as some terrestrial animals moved to a semi-aquatic lifestyle. Until now, the morphological evidence for this transition from land to water was weak.

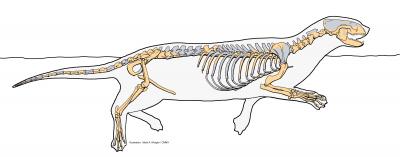

Skeletal illustration of Puijila darwini. Credit: Mark A. Klingler/Carnegie

Museum of Natural History

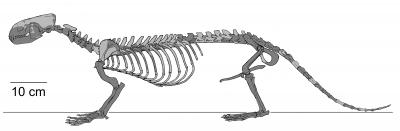

"The remarkably preserved skeleton of Puijila had heavy limbs, indicative of well developed muscles, and flattened phalanges which suggests that the feet were webbed, but not flippers. This animal was likely adept at both swimming and walking on land. For swimming it paddled with both front and hind limbs. Puijila is the evolutionary evidence we have been lacking for so long," says Mary Dawson, curator emeritus of Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Portions of the Puijila darwini specimen were found in 2007 in deposits that accumulated in what was a crater lake in coastal Devon Island, Nunavut, Canada. A subsequent visit in 2008 yielded the basicranium, an important structure for determining taxonomic relationships.

Paleobotanic fossils indicate this location during the Miocene had a cool, coastal temperate environment, similar to present-day New Jersey. Given that freshwater lakes would freeze in the winter, it is likely that Puijila darwini would travel over land to the sea for food. The transition from freshwater to saltwater in semi-aquatic mammals has been hypothesized for some time, first by Charles Darwin, who wrote in "On the Origin of Species by the Means of Natural Selection or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life", "A strictly terrestrial animal, by occasionally hunting for food in shallow water, then in streams or lakes, might at last be converted in an animal so thoroughly aquatic as to brace the open ocean."

"The find suggests that pinnipeds went through a freshwater phase in their evolution. It also provides us with a glimpse of what pinnipeds looked like before they had flippers," says Natalia Rybczynski, leader of the field expedition.

Puijila darwini is described as having a long tail, and fore-limbs comparatively proportionate to modern carnivorous land animals as opposed to pinnipeds. It is the first mammalian carnivore found at the site. Other fossils found include two taxa of freshwater fishes, one bird, and four mammalian taxa: shrew, rabbit, rhinoceros, and small artiodactyl (small short-legged herbivores, ancestors to modern giraffes and deer).

Reconstruction of Puijila darwini skeleton showing preserved bones in dark grey. Credit: Mark A. Klingler/Carnegie Museum of Natural History

The earliest well-represented pinniped, Enaliarctos—a marine form with flippers—has been found on northern Pacific shores of North America. It had been theorized for some time that pinniped evolution had been centered around the Arctic; the discovery of Puijila darwini adds credence to this theory.

Co-authors of the paper are Natalia Rybczynski, research scientist at Canadian Museum of Nature, Ottawa, Ontario; Mary R. Dawson, curator emeritus of vertebrate paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; and, Richard H. Tedford, curator emeritus of paleontology at American Museum of Natural History, New York, New York. Skeletal and fully-fleshed out illustrations of Puijila darwini were done by Mark Klingler, scientific illustrator at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

The Canadian Museum of Nature will be launching a new web section with further information on Puijila darwini. The site will go live to the public concurrently with the release of the paper in Nature. It can be found at http://www.nature.ca/newspecies.

Life reconstruction of Puijila darwini swimming in crater lake. Credit: Mark A. Klingler/Carnegie Museum of Natural History

Comments