Male mice had more changes and the mice also performed poorly in tests of short-term memory, learning ability, and impulsivity.

In three sets of experiments, University of Rochester professor of Environmental Medicine Deborah Cory-Slechta and colleagues exposed mice to high levels of air pollution, what a baby would experience sitting on a highway during rush hour, in the first two weeks after birth. The mice breathed in the pollution for four hours each day (equivalent to 10 human days non-stop each time) for two four-day periods.

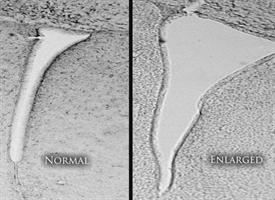

In one group of mice, the brains were examined 24 hours after the final pollution exposure. In all of those mice, inflammation was rampant throughout the brain, and the lateral ventricles -- chambers on each side of the brain that contain cerebrospinal fluid -- were enlarged two-to-three times their normal size.

Ventricles. Credit: University of Rochester.

“When we looked closely at the ventricles, we could see that the white matter that normally surrounds them hadn’t fully developed,” said Cory-Slechta. “It appears that inflammation had damaged those brain cells and prevented that region of the brain from developing, and the ventricles simply expanded to fill the space.”

The problems were also observed in a second group of mice 40 days after exposure and in another group 270 days after exposure, indicating that the damage to the brain was permanent. Brains of mice in all three groups also had elevated levels of glutamate, a neurotransmitter, which is also seen in humans with autism and schizophrenia.

Most air pollution is made up mainly of carbon particles that are produced when fuel is burned by power plants, factories, and cars. For decades, research on the health effects of air pollution has focused on the part of the body where the damage is most obvious -- the lungs. That research began to show that different-sized particles produce different effects.

Larger particles are regulated by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) but some contend that smaller particles known as ultrafine particles -- which are not regulated by the EPA -- are more dangerous, because they are small enough to travel deep into the lungs and be absorbed into the bloodstream, where they can produce toxic effects throughout the body.

That assumption led Cory-Slechta to design these experiments to show that ultrafine particles have a damaging effect on the brain.

“I think these findings are going to raise new questions about whether the current regulatory standards for air quality are sufficient to protect our children,” said Cory-Slechta.

Published in Environmental Health Perspectives.

Comments