Scientists have mapped how thousands of genetic mutations can affect a cell's chances of survival.

The study involving yeast reveals how different combinations of mutations in a single gene can influence whether the cell lives or dies.

It is the first time scientists have been able to measure the effects of every possible combination of mutations in a gene.

Researchers say the technique used in their research could aid studies into the effects of gene mutations that are linked to diseases in people.

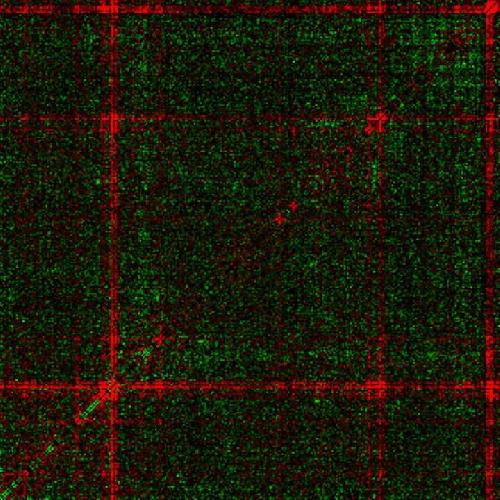

The team from the University of Edinburgh produced 60,000 strains of yeast, each with a different combination of mutations in a single gene.

They then watched the cells to see what effect the mutations had on survival and whether different combinations of genetic changes helped the yeast to fare better or worse.

In some cases, the effects of different mutations cancelled each other out and the cells survived. The effects of other mutations added together to greatly reduce the cells' chances of survival.

Genetic changes that have the greatest combined effect on survival tend to be located close to each other in the three-dimensional structure of the genetic material, the study found.

This means that the technique could help scientists to predict the shapes of molecules encoded in our genes.

The research, published in the journal Science, received funding from the Medical Research Council (MRC) and the Wellcome Trust.

Dr Grzegorz Kudla, of the University of Edinburgh's MRC Human Genetics Unit, said: "We pitted 60,000 mutated yeast strains against each other in a fight for survival. Those that survived were able to produce more copies of themselves and dominate the population. This is evolution in action.

Dr Olga Puchta, also of the University of Edinburgh's MRC Human Genetics Unit, said: "Cells without any mutations fared the best and reproduced faster than any of the mutated strains, which tells us that this particular gene has been optimally configured by evolution."

Comments