So psychologists at Arizona State University set up an experiment assessing 60 pet dogs' propensity to rescue their owners. None of the dogs had any kind of rescue training.

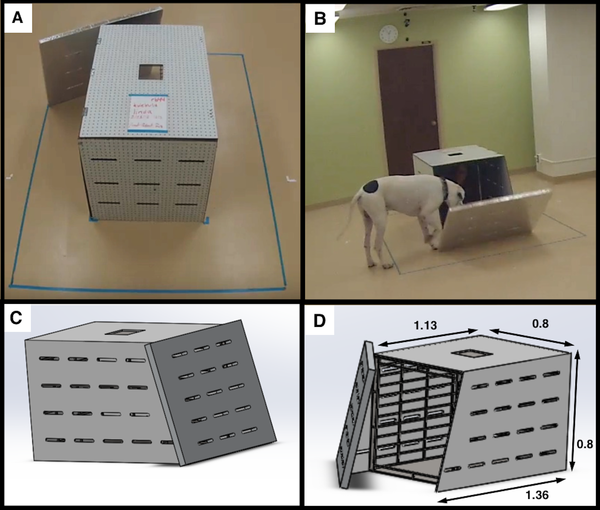

In the main test, each owner was confined to a large box equipped with a light-weight door, which the dog could move aside. The owners feigned distress by calling out "help," or "help me." Prior to the experiment, the researchers coached the owners so their cries for help sounded authentic. In addition, owners weren't allowed to call their dog's name, which would encourage the dog to act out of obedience, and not out of concern for her owner's welfare.

"About one-third of the dogs rescued their distressed owner, which doesn't sound too impressive on its own, but really is impressive when you take a closer look," says graduate student Joshua Van Bourg, but that's because two things are at stake. One is the dogs' desire to help their owners, and the other is how well the dogs understood the nature of the help that was needed. Without controlling for each dog's understanding of how to open the box, the proportion of dogs who rescued their owners might underestimate the proportion of dogs who wanted to rescue their owners.

The scholars explored that factor in control tests. In one control test, when the dog watched a researcher drop food into the box, only 19 of the 60 dogs opened the box to get the food. More dogs rescued their owners than retrieved food.

"The fact that two-thirds of the dogs didn't even open the box for food is a pretty strong indication that rescuing requires more than just motivation, there's something else involved, and that's the ability component," Van Bourg said. "If you look at only those 19 dogs that showed us they were able to open the door in the food test, 84% of them rescued their owners. So, most dogs want to rescue you, but they need to know how."

In another control test, the team looked at what happened when the owner sat inside the box and calmly read aloud from a magazine. What they found was that four fewer dogs, 16 out of 60, opened the box in the reading test than in the distress test.

"A lot of the time it isn't necessarily about rescuing," Van Bourg said. "But that doesn't take anything away from how special dogs really are. Most dogs would run into a burning building just because they can't stand to be apart from their owners. How sweet is that? And if they know you're in distress, well, that just ups the ante."

The fact that dogs did open the box more often in the distress test than in the reading control test indicated that rescuing could not be explained solely by the dogs wanting to be near their owners.

The researchers also observed each dog's behavior during the three scenarios. They noted behaviors that can indicate stress, such as whining, walking, barking and yawning.

"During the distress test, the dogs were much more stressed," Van Bourg said. "When their owner was distressed, they barked more, and they whined more. In fact, there were eight dogs who whined, and they did so during the distress test. Only one other dog whined, and that was for food."

What's more, the second and third attempts to open the box during the distress test didn't make the dogs less stressed than they were during the first attempt. That was in contrast to the reading test, where dogs that have already been exposed to the scenario, were less stressed across repeated tests.

"They became acclimated," Van Bourg said. "Something about the owner's distress counteracts this acclimation. There's something about the owner calling for help that makes the dogs not get calmer with repeated exposure."

In essence, these individual behaviors are more evidence of "emotional contagion," the transmission of stress from the owner to the dog, explains Van Bourg, or what humans would call empathy.

"What's fascinating about this study," says ASU Psychology Professor Clive Wynne, "is that it shows that dogs really care about their people. Even without training, many dogs will try and rescue people who appear to be in distress -- and when they fail, we can still see how upset they are. The results from the control tests indicate that dogs who fail to rescue their people are unable to understand what to do -- it's not that they don't care about their people.

Comments