For eight years I have studied digital nomadism, the millennial trend for working remotely from anywhere around the world. I am often asked if it is driving gentrification.

Before COVID upended the way we work, I would usually tell journalists that the numbers were too small for a definitive answer. Most digital nomads were traveling and working illegally on tourist visas. It was a niche phenomenon.

Three years into the pandemic, however, I am no longer sure. The most recent estimates put the number of digital nomads from the US alone, at 16.9 million, a staggering increase of 131% from the pre-pandemic year of 2019.

The same survey also suggests that up to 72 million “armchair nomads”, again, only in the US, are considering becoming nomadic. This COVID-induced rise in remote working is a global phenomenon, which means figures for digital nomads beyond the US may be similarly high.

The profitability of short-term lets in Lisbon is driving rents up for local people. Diego Garcia/Unsplash

My research confirms that the cheaper living costs this trend has brought to those able to capitalize on it can come with a downside for others. Through interviews and ethnographic fieldwork, I have found that the rise of professional short-term-let landlords, in particular, is helping to price local people out of their homes.

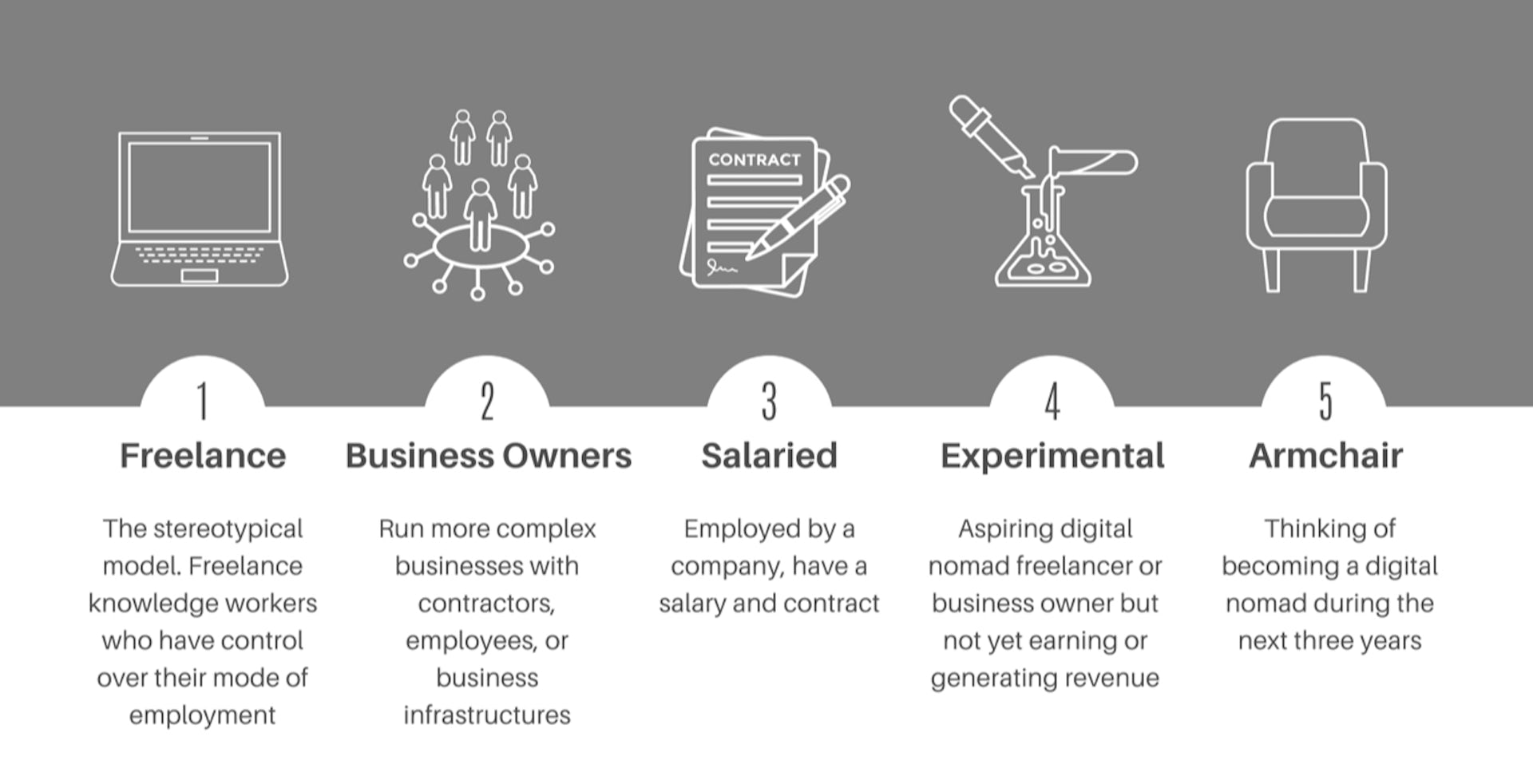

Before the pandemic, digital nomads were mostly freelancers. My research has identified four further categories: digital nomad business owners; experimental digital nomads; armchair digital nomads; and, the fastest emerging category, salaried digital nomads.

The five categories of digital nomad:

Dave Cook, CC BY

In the US, the number of salaried nomads – full-time employees now working fully remotely – is estimated to have gone from 3.2 million in 2019 to 11.1 million in 2022. This exponential growth has prompted governments to start paying attention. Last September I gave expert testimony to the UK Treasury on what they called “cross-border working”.

The phenomenon is reshaping cities. Chiang Mai in northern Thailand is often dubbed the digital nomad capital of the world. The Nimmanhaemin area, AKA Nimman or sometimes Coffee Street, brims with coffee shops, co-working spaces, Airbnbs and short-term lets affordable to people on western wages but out of reach for many locals.

For local business owners hit by the pandemic, the return of visitors to Chiang Mai is a relief. But as one Thai Airbnb owner told me:

There needs to be a balance. We used to live here when Nimman was a quiet neighborhood.

Chiang Mai’s coffee shops cater largely to foreign visitors. Duy Vo/nsplash

The purchasing power remote western workers wield

Lisbon is similarly sought out for the better weather and lower living costs it offers. Buzzwords like the “circular economy” or the “sharing economy” are often used by digital nomads to describe why such locations are so suited to their way of living. They describe new approaches to urban living that emphasize mobility, more flexible approaches to building use and re-use, and innovative business models that encourage collaboration.

But the Portuguese capital, like many other urban centers, is in the grip of a housing crisis. Activists, like Rita Silva, of Portuguese housing-rights organization Habita!, say this influx is making things worse for local people:

We are a small country and Lisbon is a small city, but the foreign population is growing and is very visible in coffee shops and restaurants.

To Silva’s mind, what she calls “this bullshit of the circular economy” does not accurately describe what is happening on the ground. In certain parts of the city, she says, you don’t hear Portuguese anymore, you hear English. This is driving up living costs, well beyond the popular tourist hotspots like Barrio Alto and Principe Real.

Co-working spaces and creative hubs are now appearing in previously traditional working-class areas. With the average salary in Portugal under US$20,000 (£16,226), these are clearly are not aimed at local people. A one-bedroom apartment in these digital nomad hotspots accounts on average for at least 63% of a local wage – one of the highest ratios in Europe.

In his 2007 bestseller, The Four-Hour Workweek, author and podcast host Tim Ferris coined the term “geo-arbitrage” to describe the phenomenon of people from higher-income countries – the US, Europe, South Korea – wielding their wages in lower-cost countries.

For some nomads, this is an essential life-hack. For others, it represents the polarizing reality of glottalization: that the entire world should operate as an open, free market. To many, it is unethical.

Urban sociologist Max Holleran points out the “incredible irony” at play:

Some people are actually becoming digital nomads, because of housing prices in their home countries. And then their presence in less wealthy places, is tightening the housing market leading to displacement in places in the global south [developing countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America].

On a visit to Chiang Mai in 2019, I booked an Airbnb. I expected to be checked in by the owner. Instead, I was met by someone called Sam (not their real name), who didn’t know the name of the person I have been corresponding with.

In the building’s lobby, a sign for the attention of travelers, tourists and backpackers clearly stated: “This place is NOT A HOTEL. Day/week rentals are NOT ALLOWED.” Yet, in the reception area, people worked on laptops, amid a constant procession of western visitors entering and leaving, with backpacks and wheely suitcases.

I looked back at my booking and realized that the apartment was hosted by a brand I’ll call Home-tel, which, other visitors confirmed, also hosted 17 other apartments. A local resident said they were considering selling up, or, failing that, renting to a professional short-term-let host. Living there had become unbearable.

I vowed that next time I traveled, I would check I was renting from a bona fide private owner. And I did. Only to find, on arrival, a large sign in the lobby stating, “No short-term lets”. When I confronted the European owner, she said the sign was already there when she purchased the apartment. “What can you do?” she said. “Money talks.”

Holleran explains that the rise in digital nomad numbers is fostering competition between destinations:

If Portugal says, “We’re sick of nomads,” and cracks down on visas, Spain can then say, “Oh, come here.” And that will be even more true in low GDP countries.

Silva says digital nomads need to be aware of the impact they have. She is also urging the Portuguese government to take meaningful regulatory action:

The majority of the Airbnbs are from companies controlling multiple properties. We want houses to be places where people can live.

By Dave Cook, PhD Candidate in Anthropology, UCL. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()

Comments