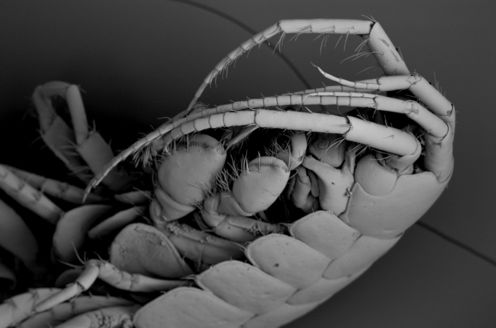

Up close and personal with the demon shrimp. Amaia Green Etxabe - University of Portsmouth

By Alex Ford,University of Portsmouth

Demon vs killer shrimp sounds like the latest CGI movie to come out of Hollywood. But in fact these are two particularly pernicious crustaceans that have been making their way westward across Europe from countries surrounding the Black Sea, eradicating native freshwater rivals en route.

Unlike the meatier species we might be more familiar with from our dining plates, the killer shrimp (Dikerogammarus villosus) and the demon (D. Haemobaphes) are technically amphipods, a group of small, flattened, shrimp-like creatures.

They’re barely bigger than a finger nail, yet they possess the most striking and dramatic of common names.

The titles are somewhat justified. These shrimp not only out-compete the slightly smaller native (Gammarus pulex) for space and food, as often happens with invasive species, they go much further – killer and demon shrimp directly prey on the hapless locals. The equivalent would be grey squirrels not only out-competing and spreading disease among the arguably cuter native red squirrel but also actively hunting and eating them.

The killer shrimp reached the UK in 2010 and within a year was denounced by the Environment Agency as the nation’s single most damaging invasive species. The demon was discovered in Britain in 2012 but has spread substantially further throughout the country’s river systems; in shrimp terms, it seems demons are even worse than killers.

Demon shrimp are measured in millimetres. Amaia Green Etxabe - University of Portsmouth

Yet it is the evocative names given to their worst enemies that may yet save the native shrimp and their ecosystem. When a charismatic animal faces eradication through habitat loss, pollution or competition from invaders, the public are likely to take notice. Great news if you’re an elephant, say, or a red squirrel.

Very often though, the tiniest animals go ignored despite their hugely important role in sustaining food chains – there’s a reason the WWF uses a panda for its emblem rather than a shrimp.

Whoever coined the phrases “killer” and “demon” shrimp, therefore, did so in a moment of genius. The names have captured the public imagination and the idea of an evil crustacean has generated considerable interest.

Facing the demons

Invasive species are said to cost the UK economy a staggering £1.7 billion through eradication programmes and the economic and ecological damage to fisheries and tourism.

Given the expense and upheaval involved in fighting the invaders, perhaps we should just leave things alone – after all, does it really matter to the ecosystem if one tiny crustacean replaces another?

It’s an important question. Invasive species don’t always slot neatly into food-webs where the last species disappeared. Instead, as in the case of killer shrimp and potentially the demon, these omnivorous creatures can occupy multiple parts of a food chain.

Consequently, this has the potential to change the food transfer from plants right through to certain fish, bird and mammal species.

The native shrimp primarily feeds on fallen leaf litter and vegetation while the invaders also eat fish eggs/larvae, insects and “rival” shrimp.

Killer shrimp finds a tasty fish egg.

The new arrivals might also breed at different times, grow at different rates, have different numbers of young and carry different diseases and parasites. The various species of micro-shrimp may look fairly similar to us humans, but any switch has the potential to deeply upset the natural balance of an ecosystem.

Diseases and parasites

Invasive species often bring with them diseases and harmful parasites and it seems these shrimp are no different. Our research at the University of Portsmouth found that demon shrimp have carried multiple parasites with them across Europe.

We don’t yet know what these parasites will do in newly invaded areas but we do know they are playing havoc with sexuality. Our research found at least 50% of the invasive male shrimp show sexual abnormalities. These sexually abnormal (termed intersex) shrimp display female characteristics caused by feminizing parasites either caught in the UK or most likely carried inside the invaders. Interestingly, these parasites don’t appear to feminize as well in British waters.

Such gender issues however haven’t hampered the demon’s ability to wipe out its British cousin. Therefore we also have to consider the parasites who live “within” the native species which can become collateral damage in the shrimp wars.

These parasites are important too as they often pass through snails or crustaceans and finally into fish or birds. Gammarus shrimp carry worm-like parasites called Acanthocephala (spiny-headed worms), for instance. These parasites can “take over” the shrimp, flooding it with serotonin and altering its behavior so that the shrimp swims nearer the surface and is more likely to eaten by birds such as ducks.

Other species of Acanthocephala have fish such as trout as their final hosts. The extinction of an intermediate host, such as the native shrimp, therefore breaks the link in the parasite life cycle, with impact felt elsewhere in the food web.

Who cares, one might ask, parasites are bad right? Not necessarily. Studies have shown that ecosystems with fewer parasites are less diverse than those with many, therefore the replacement of one shrimp species for another might not necessary replace the parasites which strengthen the food web.

It’s difficult to know how to stop the spread of these invasive shrimp. Public awareness campaigns are reminding people to check, clean and dry themselves and their equipment to hinder the movement of these critters but only time will tell whether we are witnessing the extinction of the native Gammarus shrimp in British waterways. Britons may soon have to get used to killers lurking in their lakes, and demons in their rivers.![]()

Alex Ford, Reader in Biology at University of Portsmouth, receives funding from UK Environment Agency, Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and EU Interreg program (PeReNE) to study parasites and the reproductive and neuro-endocrine disruption of crustaceans

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Comments