Recently, researchers have noticed that the detectors at MINOS occasionally detect particles from the atmosphere, and that these detections correlate with weather patterns in the high atmosphere.

MINOS was designed to study neutrinos - exotic particles that rarely interact with matter. Although they are present all around us, they are extremely difficult to detect - especially against the background noise of the universe. That's why the MINOS experiment is located in an abandoned iron mine in northern Minnesota. To study them, physicists at Fermilab in Illinois create a beam of high-energy neutrinos and aim it toward the MINOS detector 450 miles away. After traveling through 5,000 tons of iron, a few of the millions of neutrinos will interact with the detector.

Fortunate Side Effect: A particle the MINOS detector was filtering out as noise turned out to provide some clues about the temperature of the stratosphere. Photo Credit: MINOS

MINOS was designed to study neutrinos - exotic particles that rarely interact with matter. Although they are present all around us, they are extremely difficult to detect - especially against the background noise of the universe. That's why the MINOS experiment is located in an abandoned iron mine in northern Minnesota. To study them, physicists at Fermilab in Illinois create a beam of high-energy neutrinos and aim it toward the MINOS detector 450 miles away. After traveling through 5,000 tons of iron, a few of the millions of neutrinos will interact with the detector.

MINOS has been detecting neutrinos from Fermilab for two years now. What scientists have recently realized is that they are also detecting particles called muons from elsewhere - 20 miles up in the atmosphere. During the summer months, air in the upper atmosphere expands so that there is more space between the atoms. More space means mesons, which decay into muons when they don't hit air molecules, can get through the atmosphere, leading to an increase in the muon count. However, short-term spikes in muon counts were also being seen in the winter months - usually lasting for a few days.

This means that the temperature of the stratosphere was increasing dramatically (in some places as much as 40° C) for short periods of time. When they compared the data with meteorological observations of the atmosphere, they found that they were observing a phenomenon called sudden stratospheric warming. Now, potentially, they can use cosmic ray data to detect and measure these warming events.

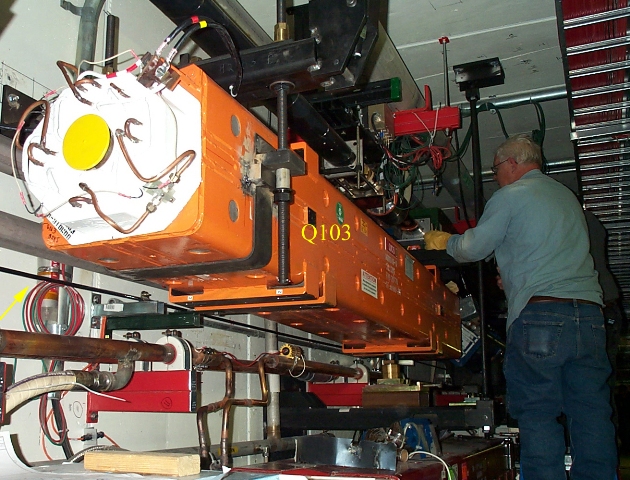

Neutrino Generator: Engineers install NuMI - the generator at Fermilab that sends a beam of neutrinos underground 450 miles to the MINOS detector. Photo Credit: MINOS

Lead scientist for the National Centre for Atmospheric Science, Dr Scott Osprey said: "Up until now we have relied on weather balloons and satellite data to provide information about these major weather events. Now we can potentially use records of cosmic-ray data dating back 50 years to give us a pretty accurate idea of what was happening to the temperature in the stratosphere over this time. Looking forward, data being collected by other large underground detectors around the world, can also be used to study this phenomenon."

Muons are detected by MINOS so that they can be filtered out of the background noise that poses problems for neutrino detection. It's lucky that the data exists, because now scientists can begin to correlate what was once useless data with atmospheric phenomena.

Professor Jenny Thomas, deputy spokesperson for MINOS from University College London said, "The question we set out to answer at MINOS is to do with the basic properties of fundamental particles called neutrinos which is a crucial ingredient in our current model of the Universe, but as is often the way, by keeping an open mind about the data collected, the science team has been able to find another, unanticipated benefit that aids our understanding of weather and climate phenomena."

I guess sometimes a little extra noise can be useful.

Comments