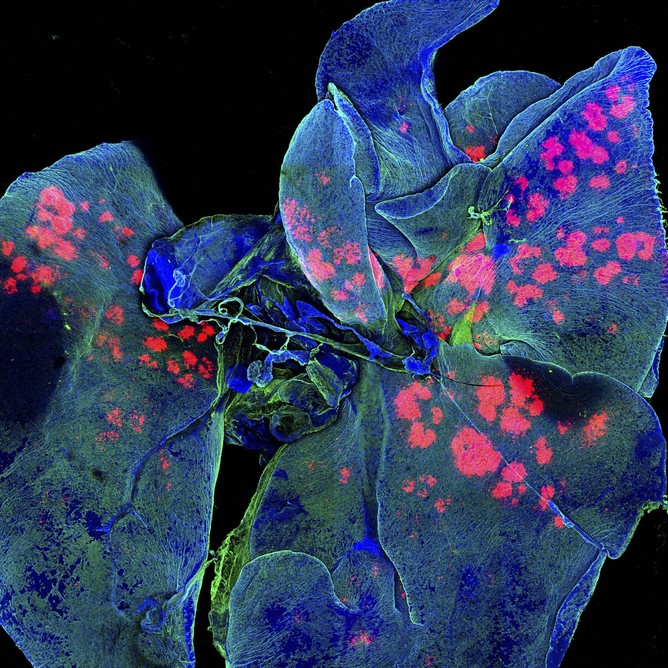

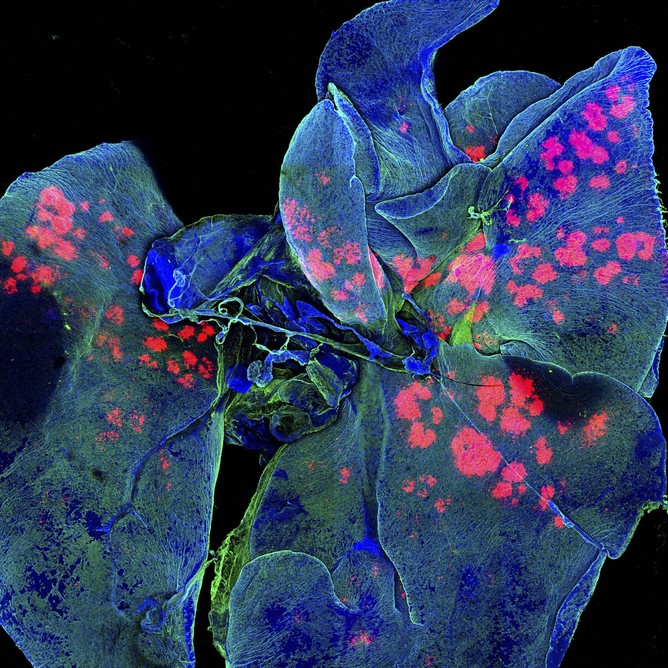

Not Just The Holidays: The Hormonal Shift Of Perimenopause Could Be Causing Weight Gain

Not Just The Holidays: The Hormonal Shift Of Perimenopause Could Be Causing Weight GainYou’re in your mid-40s, eating healthy and exercising regularly. It’s the same routine that...

Anxiety For Christmas: How To Cope

Anxiety For Christmas: How To CopeChristmas can be hard. For some people, it increases loneliness, grief, hopelessness and family...

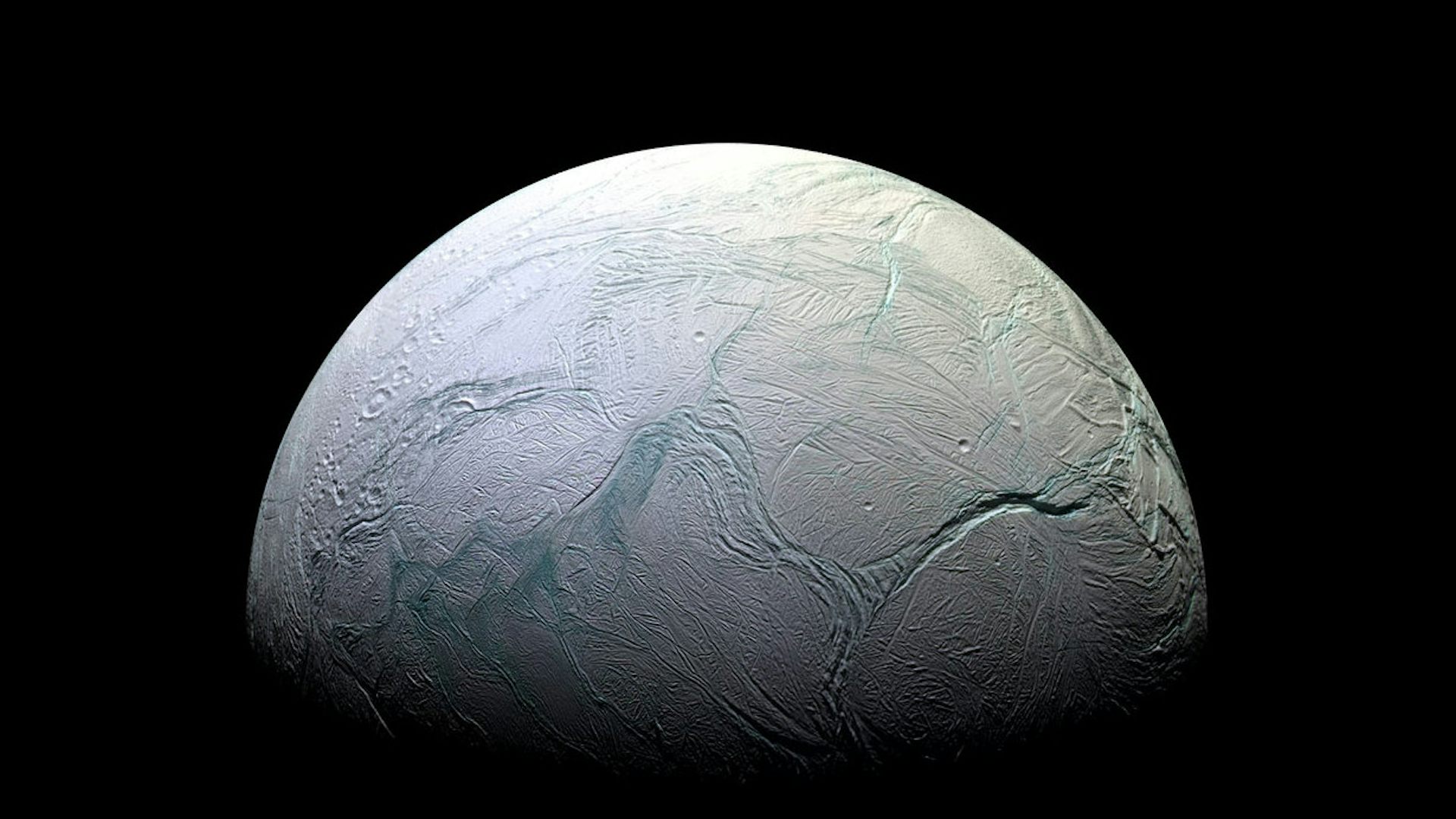

The Enceladus Idea In The Search For Life Out There

The Enceladus Idea In The Search For Life Out ThereA small, icy moon of Saturn called Enceladus is one of the prime targets in the search for life...

Deontological Decisions: Your Mother Tongue Never Leaves You

Deontological Decisions: Your Mother Tongue Never Leaves YouΙf you asked a multilingual friend which language they find more emotional, the answer would usually...