I want to be the first to congratulate Todd Douglas Miller on his 2020 Academy Award, because unless someone pumps out a documentary about a minority transgender person with their heart on the outside who escapes North Korea and wins the Olympics, this is going to win.

And for good reason. It looks glorious, it feels glorious, it hearkens back to a time when NASA was bold and not a job works program. As a kid who lived a short distance from Cape Canaveral, I was fortunate to see an Apollo launch in person, and I have to tell you this is better.

This is better because we're living in a great period for film, when Peter Jackson can bring footage from the Great War (called such before a second such war relegated it to being World War One) to life and a creator like Miller and his team can make the first moon landing look new just the same way.

This beautiful shot of the Apollo 11 liftoff is available at the Apollo 11 image library.

When that 1202 alarm goes off, you will have a feeling of dread like they probably had. I know how the story ends, we all do, but you will feel like you are in the module when Charlie Duke says it should be fine unless it happens again and you can hear the nervousness in his voice. And then it does happen again. And again.

But the whole thing is gripping, aided by a terrific score. Miller credits the astronauts and engineering team as cinematographers, which is both charming and true, but it was syncing sound and video, a painstaking task when dealing with so many formats, and knowing what to include that makes art. Who won't be struck by the video of 28-year-old senior controller JoAnn Morgan alone among all those men in the firing room?

The 90 minutes fly by nearly as quickly as Columbia does around the moon and I was ready to sit there all day. It really is a terrific film.

|  |  |  |  |

Errata

To clear it up if you've already seen it, the 1202 alarm was a warning that the computer itself was out of processing power. You probably already know that The Apollo Guidance Computer was a single processor computer and that all of NASA itself had less computing power than your smartphone. Though most of NASA was defense contracts (Mercury astronaut Gus Grissom had joked that he felt comfortable even though he was sitting on top of a solid rocket fueled government program where all the contracts went to the lowest bidder) the guidance computer had been designed by MIT’s Instrumentation Lab and so it could interrupt a running program if something more important came up, and in simulations the code developed by Margaret Hamilton and her team worked fine.

Margaret Hamilton, who would get the Presidential Medal of Freedom for her work. Want to see their code? You can read it here.

But there is a saying about how something is academic and therefore not the real world, and in the real world the rendezvous radar in the lunar module, which was sending its location to the command-service module, was running in the background and taking up just enough space that other programs could not run, like the the Vector Accumulator (VAC) area. The background processes (the programmers later attributed the error to the crew, so Hamilton didn't just invent the term "software engineering", she brought blaming 'pilot error' into the space age!) threw a 1201 and 1202 error and it caused a software reboot. And then it happened again. While they were trying to land on the moon.

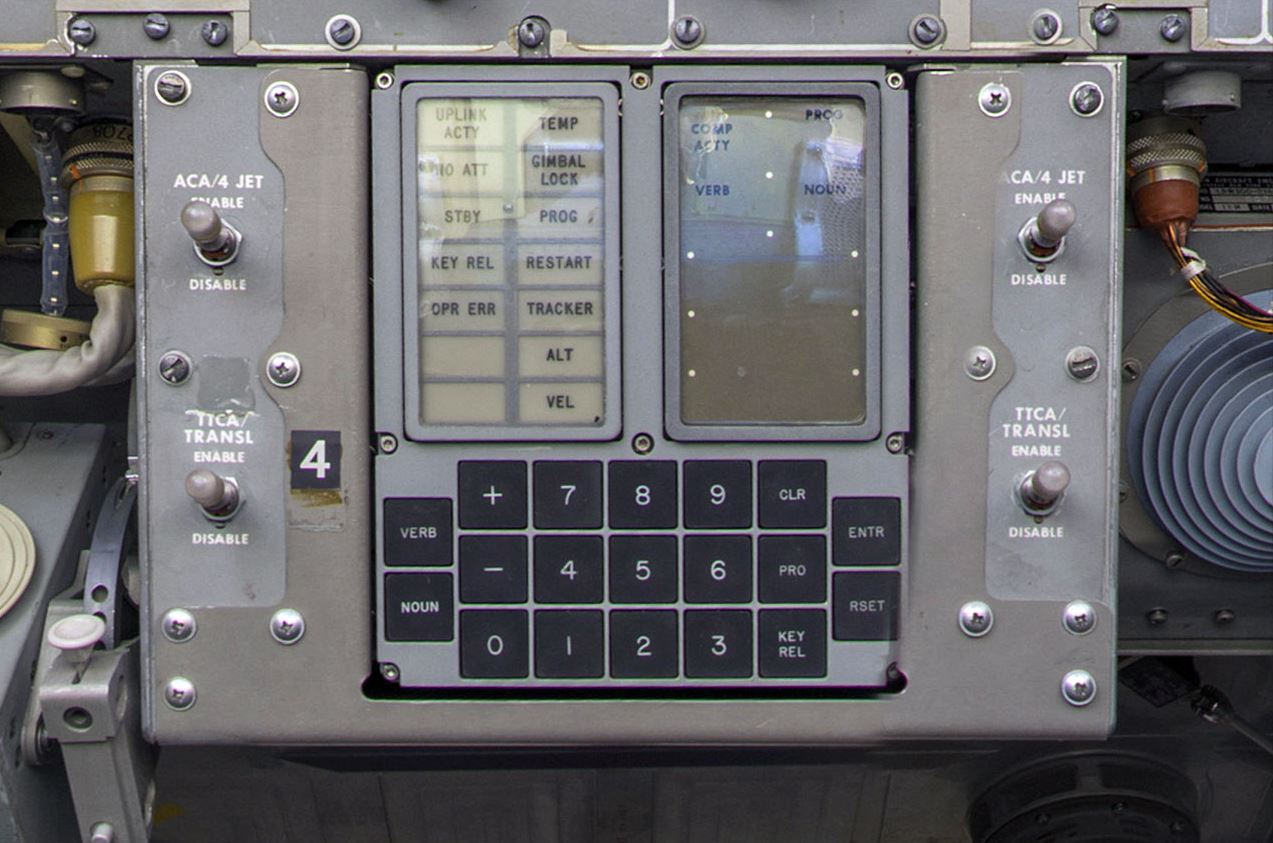

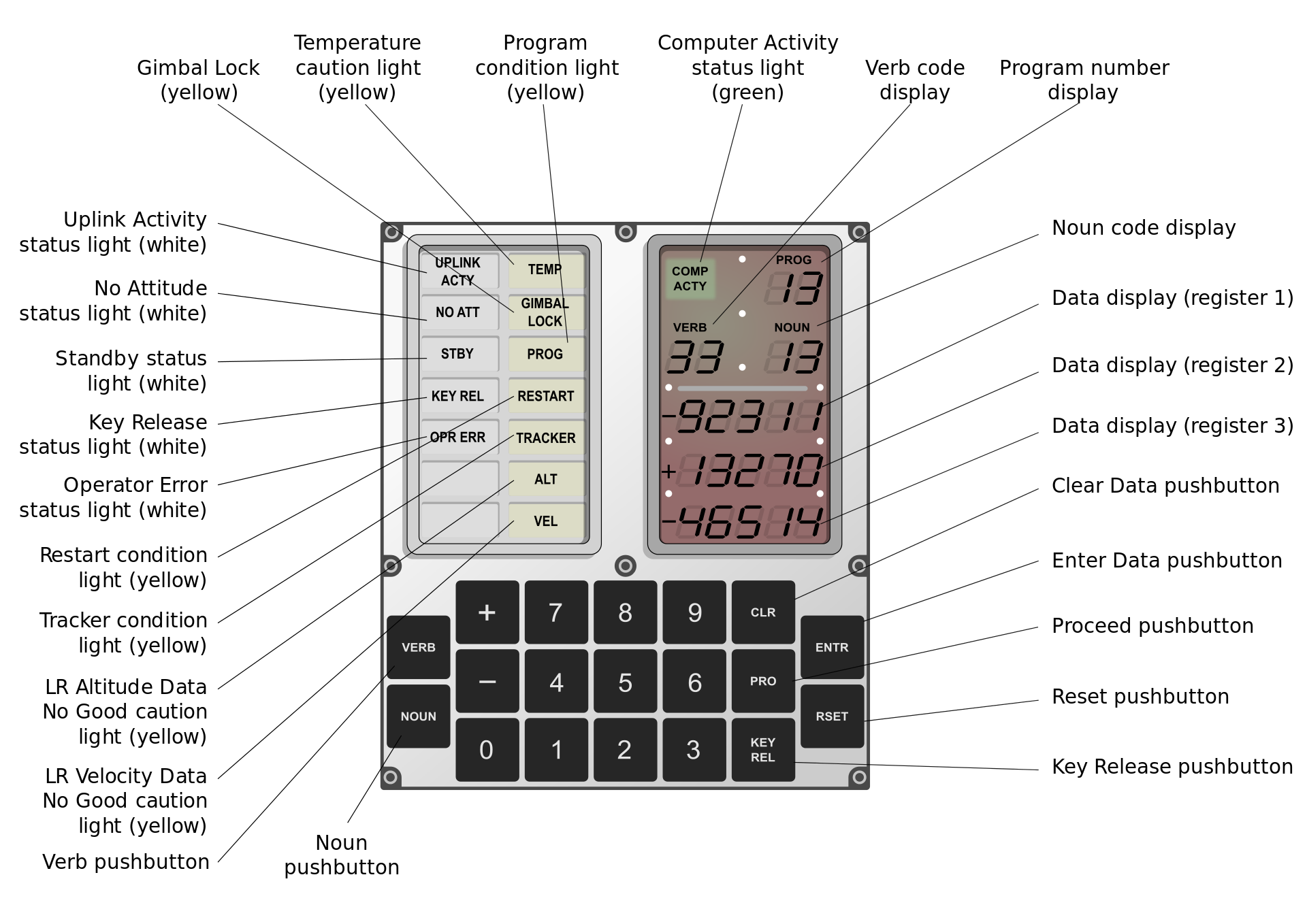

Here is what it all means, thanks to Oona Räisänen, who made this in Inkscape based on the Apollo Operations Handbook and a NASA photo.

Quickly, Eagle lunar module pilot Buzz Aldrin, whose heart rate had seemingly never gone above 88 beats per minute no matter what was going on, must have jumped a little when he noticed that in the short number of commands in the tiny computer it froze in the same place. “Same alarm, and it appears to come up when we have a 16/68 up,” he said, meaning Verb 16 Noun 68, which displayed the range to the landing site and their velocity. So he asked Houston Mission Control for that data instead of calling it up from the computer. The computer was staying up just long enough to transmit its date before throwing the alarm again that it was still updating properly.

All those guys were rocks, but Buzz Aldrin really had nerves of steel and after seeing this film, you will know it.

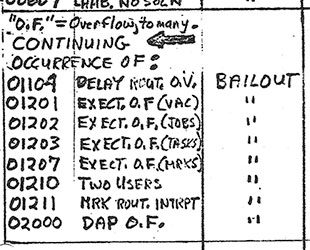

But he had confidence in Jack Garman and the crew on the ground also, who had nerves of their own. Though just a young guy, almost the entire NASA program was run by people so young we don't even think they can buy their own health insurance now, at age 24 he had been tasked with finding what all of the potential alarms were and when he heard 2012 he went to his handwritten sheet.

Credit: Collectspace.com

Nearly every alarm triggered an abort in simulation but with seven minutes to go until landing on the moon in the real world, he felt an alarm showing the guidance computer was being overloaded and was exceeding the cycling time available was not perilous. Had he panicked, he would have caused the mission to fail. If they had died, he would've been the villain.

Comments