An intrepid archaeologist is well on her way to dislodging the prevailing assumptions of scholars about the people who built and used Maya temples.

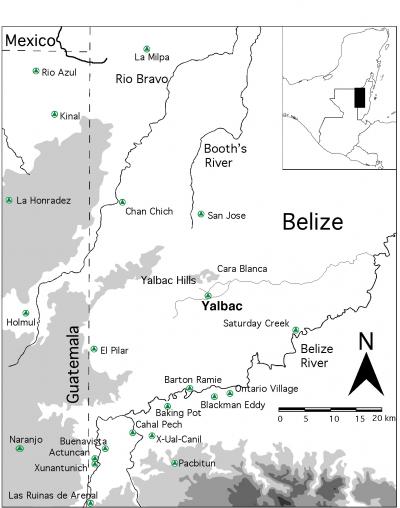

From the grueling work of analyzing the “attributes,” the nitty-gritty physical details of six temples in Yalbac, a Maya center in the jungle of central Belize – and a popular target for antiquities looters – primary investigator Lisa Lucero is building her own theories about the politics of temple construction that began nearly two millennia ago.

Her findings from the fill, the mortar and other remnants of jungle-wrapped structures lead her to believe that kings weren’t the only people building or sponsoring Late Classic period temples (from about 550 to 850), the stepped pyramids that rose like beacons out of the southern lowlands as early as 300 B.C.

“Preliminary results from Yalbac suggest that royals and nonroyals built temples,” said Lucero, a professor of anthropology at the University of Illinois.

In fact, judging by the varieties of construction and materials, any number of different groups – nobles, priests and even commoners – may have built temples, Lucero said, and their temples undoubtedly served their different purposes and gods.

That different groups had the wherewithal – the will, resources and freedom – to build temples suggests to Lucero that “the Maya could choose which temples to worship in and support; they had a voice in who succeeded politically.”

Yalbac’s location on the eastern periphery of the southern Maya lowlands and its distance from regional centers may explain its particular dynamics and its “relative political independence,” Lucero said.

The archaeologist’s new propositions challenge academic thinking on Maya temples.

“Maya scholars have basically assumed that rulers built all the temples,” she said. “No one has questioned this, although cross-cultural comparison alone would suggest otherwise.”

o be sure, the historic record is largely silent on why the Maya, a complex culture with many mysteries still to unravel, had several temples in any given center, which is why Lucero, among others, believes that archaeologists must seek answers from the buildings themselves and “construct more creative ways to assess what temple attributes can reveal about their non-material qualities.”

Lucero’s latest findings are detailed in the most recent issue of Latin American Antiquity in an article titled “Classic Maya Temples, Politics, and the Voice of the People.”

Lucero is the leading expert on Yalbac and the sole authorized archaeologist on the site, authorized by the Belize Institute of Archaeology. She has conducted research in the area since 1997, and on the Yalbac site since 2002. The work Lucero is doing will provide the basis for her next book project, an exploration of temples as text.

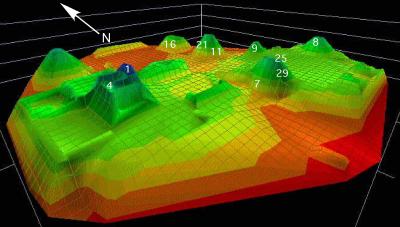

While largely unknown – except to looters and loggers – Yalbac is a rich site. In addition to the six temples, it also includes two plazas, a large royal residence or acropolis, and a ball court. Several of the temples are likely royal, three likely residential or memorial. None so far has been cleared of surface debris. Only one of the temples has escaped looting.

Looters, ironically, paved the way for Lucero’s work to map, excavate and analyze Yalbac’s Late Classic period temples. Over the years, thieves have carved nine trenches into the site in their pursuit of priceless booty. These same trenches have become Lucero’s access routes to the temples. Still, in order to reduce additional invasion and damage to the historic site, Belizean authorities restrict her excavation beyond the trenches.

Some of the evidence she is accumulating is in the tons of fill – cobbles, boulders and stone pebbles, some in the tons of mortar – marl, plaster, and various kinds of loam.

Lucero – either on her own or leading groups of archaeology field school students – has been able to map the Yalbac site, including its structures, looters’ trenches and stelae – upright marker stones, sometimes inscribed, erected by the Maya over the millennia.

Over the years, she has dated ceramics found at Yalbac from about 300 B.C. through A.D. 900; her plaza test pit excavations have exposed floors that date to the same period, “a typical occupation history for Maya centers.”

“We also have placed test units throughout the site to get an idea as to monumental architecture construction histories and functions.”

To date she has taken four New Mexico State University field school classes to Yalbac. She will take her first U. of I. field school class this May for a six-week hands-on course in archaeological survey and excavation. Lucero joined Illinois’ department of anthropology last August, after a decade at NMSU.

The focus this summer will be on profiling the temple looters’ trenches and test excavations. Lucero and 10 undergraduates and two graduate assistants will collect data from the six temples in order to compare temple frequency, size differences, location, layout, accessibility, history of use, construction patterns, surface decoration and ritual deposits.

“We also will expand the trenches to see if the looters missed caches – artifacts consisting of shell, jade, ceramics, lithics, etc. – that may provide clues as to temple function and purpose.”

Lucero doesn’t spend much time worrying about looters.

“While looting is still a problem, the relatively new management of the land-owning company, Yalbac Cattle and Ranch Co., which logs the 200,000 acres they own, have armed patrols that protect the area from illegal poachers, loggers and looters.”

Because Yalbac is directly behind the guardhouse, she said, “the site is very well protected, as are the students and staff.”

“We have been surveying the area for years without any problems,” she said. “Often the loggers show us sites they have found in the process of searching for mahogany, cedar and rosewood.”

Comments