Synchrotron x-ray is becoming the star treatment of choice for study of high-profile artifacts. Radiation produced by synchrotrons, nearly light-speed electrons stuck in a circular path, provides the brightest known x-rays. It reveals information lost to standard x-ray, including the specific detection of a wealth of chemicals and minerals. Synchrotron x-ray has been most frequently used for material science, though it has already proved its mettle as a detector of biological remains by revealing the presence of ritual blood on archaeological relics from Mali.

Synchrotron radiation x-ray techniques helped to rewrite art history as well. Until last June, the technique of oil painting was thought to have first originated in 15th century Europe. X-ray examination shattered this misconception with the revelation that Buddhist paintings found on the Silk Road used oil as early as the 7th century AD.

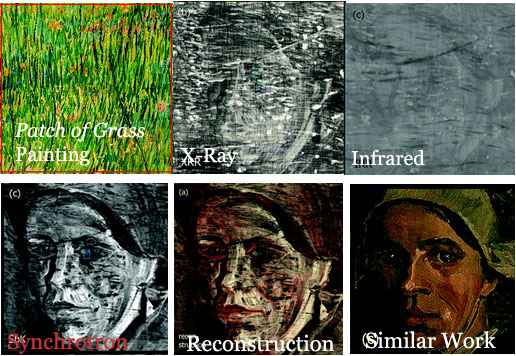

Synchrotron radiation x-ray techniques helped to rewrite art history as well. Until last June, the technique of oil painting was thought to have first originated in 15th century Europe. X-ray examination shattered this misconception with the revelation that Buddhist paintings found on the Silk Road used oil as early as the 7th century AD. This x-ray technique also helped to find one of Van Gogh’s lost paintings. The impressionist master was notorious for reusing canvasses, painting over existing works (a practice known as palimpsesting). His 1887 Patch of Grass painting has been known to conceal a much different painting beneath its energetic, directional strokes. A synchrotron x-ray scan of the painting permitted researchers to reconstruct the painting in illuminating detail, prompting the Kröller-Müller Museum in The Netherlands to call for x-ray examination of all of Van Gogh’s works in their collection.

Similar studies have been done on NC Wyeth’s work, revealing a bellicose magazine illustration recycled into the more staid unfinished “Family Portrait”. And pages of Archimedes’ texts have been revealed under two layers of overwriting.

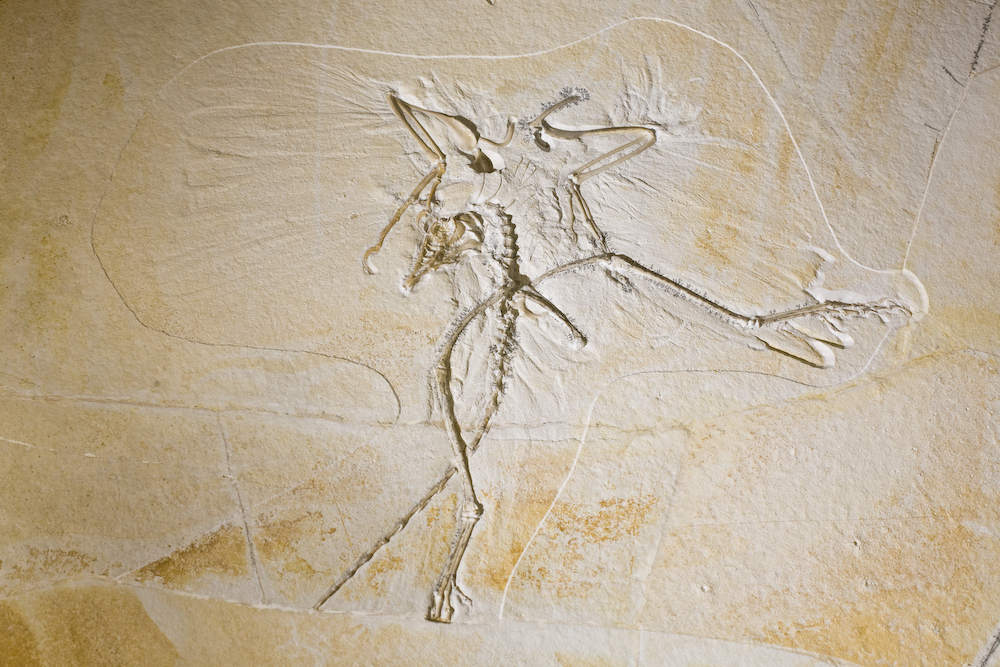

Synchrotron x-ray is emerging as a scientific complement to historiography, telling us how our historic and prehistoric records came to be and what influenced their formation. From the archaology to the archaeopteryx to art, from paleontology to a panoply of palimpsested paintings, advanced X-ray techniques help us to find the story beneath the story.

Comments