Fortunately, the editors were happy to publish a science clarification, written by yours truly - it just isn't in the print edition. That's twice in the last week the print op-ed has had anti-science cranks (they also had the Wilson 'scientists are picking on psychologists' whining that I wrote about) but only limit actual scientific responses to the website.

I understand artistic license, I understand creating some context, but is there any reason for an editor or a writer in mainstream media to make scare journalism about science the intent of a story, rather than a conclusion reached by people who also believe in ghosts?

This is the part that really got me going, and why I wrote a response:

"Among the concerns are that some small percentage of the mosquitoes released end up being female, which means that people are being bitten by a genetically engineered creature that might insert genetically engineered proteins into the person."Well, it's water under the bridge, as they say. If people get a little smarter about what science is or is not by reading my response, I am happy to help. I remain skeptical it will, though. The 'put warning labels on GMOs' campaign is in full swing and Californians are blaming everything except anti-science beliefs about medicine for the biggest Whooping Cough epidemic in 60 years.

Please click and go to the article so the LA Times is encouraged to put science in their science articles:

Fear the fever, not the Frankenbug by Hank Campbell, LA Times

Edit: They don't seem to keep some pieces archived on the website and I don't have a tearsheet or a PDF so the editor sent me the draft they published and I am including it here. You can also read it via the Wayback Machine:

Fear the fever, not the 'Frankenbug'

By Hank Campbell

July 19, 2012

"Mutated mosquitoes -- or to put it more elegantly, genetically engineered ones -- could help protect people from dengue fever. The question is whether we'll need someone to protect us from the mutant mosquitoes," begins a July 17 blog post by Karin Klein. Unfortunately, that is as close as her piece gets to science, but some understanding of genetic optimization is important to truly evaluate the benefits and risks of a proposed solution to prevent a dangerous dengue fever outbreak in the Florida Keys.

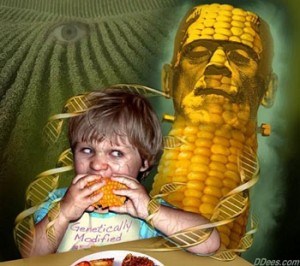

Was Frankenstein a genetically modified organism (GMO)?

Detractors of genetics like to put the term "Franken" in front of science they seek to ridicule, and Klein uses that metaphor as well. But it isn't accurate.

The Frankenstein monster was not genetically modified; it was a grafted hybrid -- like every single piece of food on dinner tables every night of the week for thousands of years. Virtually nothing people consume today has not been modified using science; tomatoes, for example, would all be the size of our thumbs if not for that "Frankenstein" approach and scientific modification. The mosquitoes to be released in Florida are not hybrids from 200-year-old fiction.

They are also not mutations, the other metaphor Klein uses.

Organic food has a lot of mutations

Scientifically, mutation happens quite often; it is one of the mechanisms of evolution. To organic food proponents, mutation is acceptable because it is natural. It is also random: Cosmic rays can break chromosomes into pieces that reattach randomly and even create genes that didn't exist before. It's all natural, but also dangerous. Science advances have taken the randomness out of organic mutations, and now biologists can precisely modify organisms to achieve one narrow benefit, like having a natural pesticide, without causing any harm to people or the environment.

The mosquitoes used to curb the spread of dengue fever are not mutated.

What about these genetically modified mosquitoes?

Dengue fever has become a concern in Florida. Policy makers are right to worry; dengue is the most common "vector-borne" (result of feeding activity) disease in the world, with 2.5 billion people at risk, according to the World Health Organization. There's no medication and no vaccine, so researchers have been working on ways to control the insects themselves without using dangerous chemicals -- something we all agree is a positive. Toward that end, a British company named Oxitec has created a genetically modified dengue mosquito strain, and in the wild those males mate with wild females.

The offspring die before they can bite people and spread the disease. Problem solved.

But when dealing with the real world, it isn’t so simple because safety is paramount, including evaluating the risks of unintended consequences.

For that reason, Brazil has a mature regulatory system for genetically modified organisms, as does the United States. Oxitec has worked on this genetically modified mosquito for 10 years, it has been in field testing for the last three. It has performed so well that both the minister of health and the minister of science and technology in Brazil are asking for Oxitec to use their mosquitoes in more places. Compare that mentality to Florida, where a real estate agent named Mila de Mier started a change.org petition to stop experts from using the Oxitec mosquito. "I don't want my family being used as laboratory rats for this," de Mier told The Guardian.

Klein essentially agrees with the real estate agent over the scientists, writing, "Before authorities release millions of whining Frankenbugs, they should know more about the potential for unintended consequences."

But authorities already do. They are the ones who asked Oxitec to come in.

The science of dengue and mosquitoes

Male Aedes aegypti mosquitoes are harmless. They don't bite and simply feed on plants. Female mosquitoes do bite, but the only way a female mosquito can acquire the dengue virus is to get it from a human with dengue. Activists seem to be more concerned about the "what if" of a female genetically modified mosquito biting someone as opposed to the real threat of a disease that impacts 100 million people in 100 countries. There is little reason for concern, for three reasons.

First, female genetically modified mosquitoes aren't being released; only the harmless males are. What if a female is accidentally released and bites someone? If you have a choice, you should hope you are bitten by a genetically-modified female rather than a "natural" one. There is no chance the genetically modified mosquito is infecting you.

Second, what about the genetic modification risk? Even if an accidentally released female were to bite someone, the Oxitec Aedes aegypti proteins are not expressed in mosquito salivary glands. It can't transmit its genetic modification.

Finally, the proteins are not toxic to humans.

In other words, concern about the mosquitoes that prevent the disease, compared to the dangers of the disease or even the pesticides to kill mosquitoes, is unwarranted. Believing otherwise requires a kind of "precautionary principle" paranoia that would prevent anyone from ever driving a car or taking any medicine.

These mosquitoes can save lives without harmful chemicals and they can't harm us. This is a win for everyone.

Hank Campbell is the founder of Science 2.0 and co-author of "Science Left Behind," coming this September.

Comments