Arguably, Galileo's biggest contribution to astronomy was the development of a 30x telescope, through which he made many of his subsequent observations and discoveries (most notably the phases of Venus, the discovery of the four largest satellites of Jupiter, and sunspots). He also argued in favor of the Copernican theory (a sun-centered universe versus the earth-centered universe).

Luckily, I happen to live in the town selected as the world-exclusive host for the Galileo, Medici and the Age of Astronomy exhibit, presented by Officine Panerai, and as I am a thoughtful Scientific Blogger, naturally I visited the exhibit in order to bring the wonder that is Galileo to you.

"The exhibit showcases Galileo's accomplishments, his relationship to the ruling Medici family, his discoveries, and his overall impact on astronomy, physics, and math," the Franklin Institute (where the exhibit was held) site says. "This will be the first time one of the two remaining Galileo telescopes has left Italy. Also exhibited will be other instruments belonging to Galileo, as well as paintings, prints, and manuscripts from the priceless Medici collection. Together, the collections will showcase how the union of science, art, and political power gave rise to Galileo's success."

The exhibit was wonderful2 and I have lots to share, so I'll break it up in to three articles. This, the first, will cover some of the objects and instruments from the Medici collection. The second will continue in that vein (there are a LOT of photos). The third will cover Galileo's contributions to optics in the 16th and 17th century. Photos abound, both official and unofficial. And yes, I was able to peer through the famous Galileo telescope (although it was just pointed at the museum's ceiling).

A fourth article will follow on a somewhat related topic - physics and art, and why I need a room in my future dream house dedicated to scientific merriment.

Should you care to listen to an audio tour of the exhibit (produced by Derrick Pitts, The Franklin Institute's Chief Astronomer), please click here.

Setting the Scene

Galileo lived in Italy during the second half of the 16th century and first half of the 17th century, late in the Italian Renaissance. The Medici had returned to power, and had hired Galileo as a tutor for several of the Medici clan. Under Cosimo I and II and Ferdinando II, Galileo worked to change science as he knew it. In fact, he named four of Jupiter's moons after some of the Medici kids.

Yet all was not pillows and potpourri in Tuscany. The Italian Wars had just ended, and a number of scientific and mathematical instruments had been instrumental (ha!) in the military campaigns, particularly for surveying. Educated men of this time were expected to know how to use a compass, divider, astrolabe, and other common tools of the engineer and architect (even artists like Michelangelo needed these skills).

Geometric and military compass. This Galilean compass is "a sophisticated and versatile calculating instrument for performing a wide variety of geometrical and arithmetical operations, essentially the slide rule of its' day."

Triangulation instrument. The Franklin Institute says this instrument "is a form of surveying device. Its inscription says it is used 'to find the distance by means of the surface.' By taking angular measurements to a distant point from two locations and using the known distance between the two measuring points, the surveyor could use simple geometry to figure out how faraway the point was."

Armillary sphere, left, and astrolabe. An armillary sphere is "an astronomical instrument is used to represent the orbits of the planets, stars, and the Sun by means of rings pivoting on a common center. Typically, at the center is a large globe representing the Earth. Surrounding brass rings portray celestial coordinates, meridians, equators, and zodiac constellations." This is essentially a 3-D astrolabe. An astrolabe is "a portable astronomical calculator used to tell the rising and setting times of the sun and a number of fixed stars in a number of locations. It can also be used to determine height and distance by the geometric method of triangulation."

Ptolemaic planisphere. For an old book, it's in great shape, and the colors are lovely.

This is a cylindrical sundial, and quite a pretty one at that. The hour markers are on the cylinder and the gnomon is the horizontal brass arm.

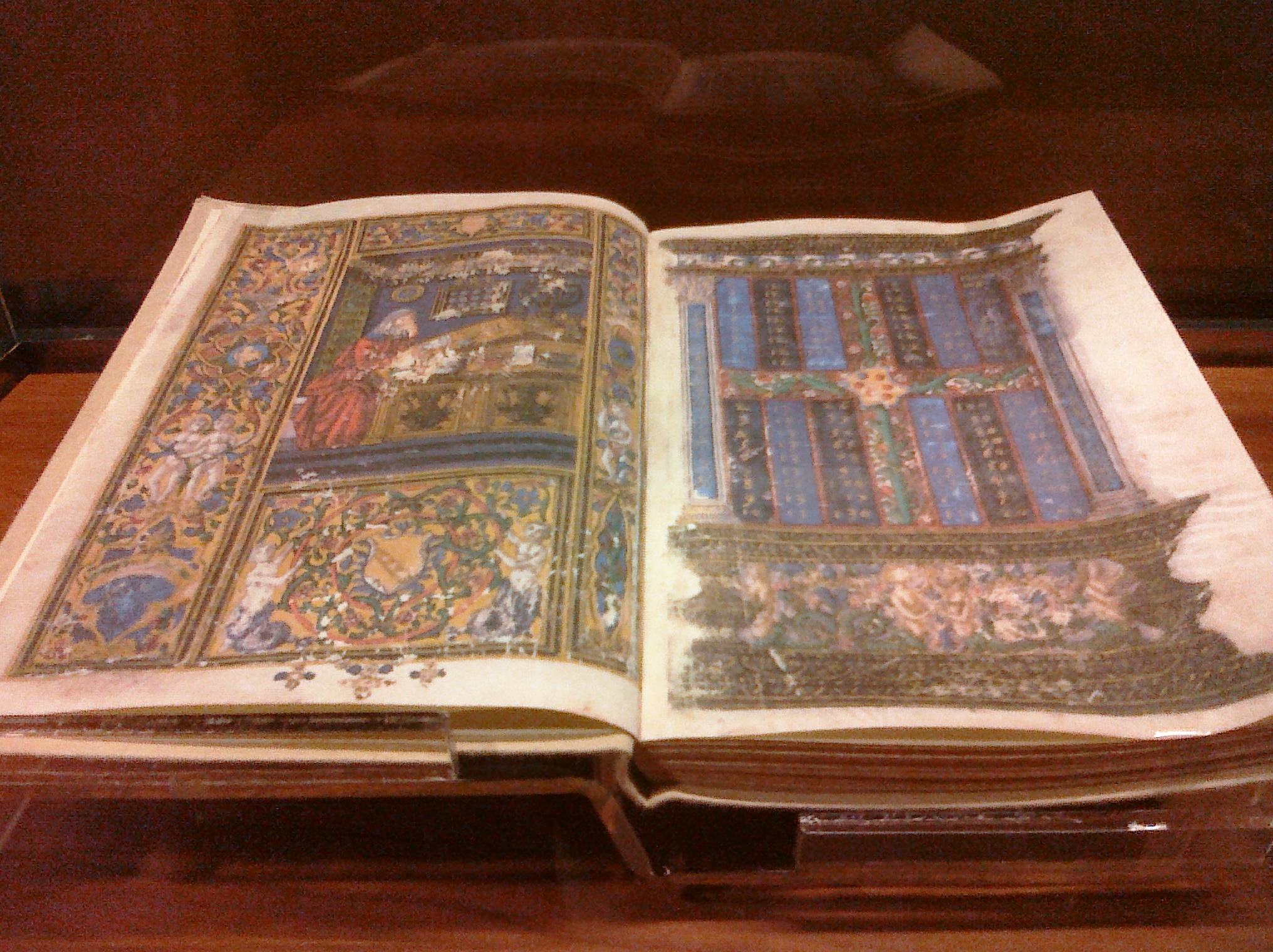

This is a treatise of "aritmetica," and features Pythagorus working in his study (the red robe in the upper left corner).

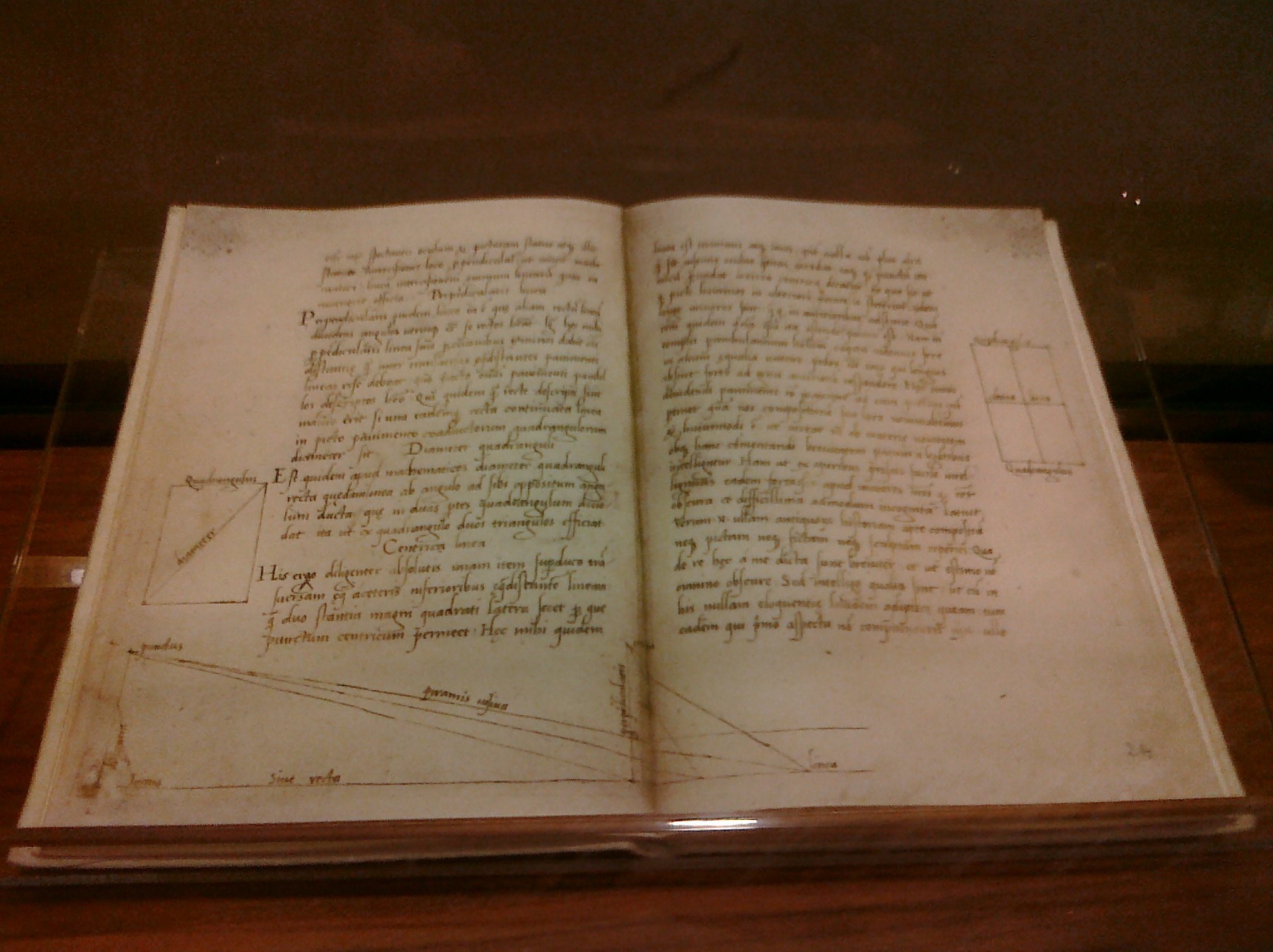

A codex on linear perspective, by Alberti, illustrating the best way for drawing in correct perspective by means of the intersection of the visual pyramid.

A beautiful surveying compass, gilt and enameled brass.

A nine-sided polyhedral sundial.

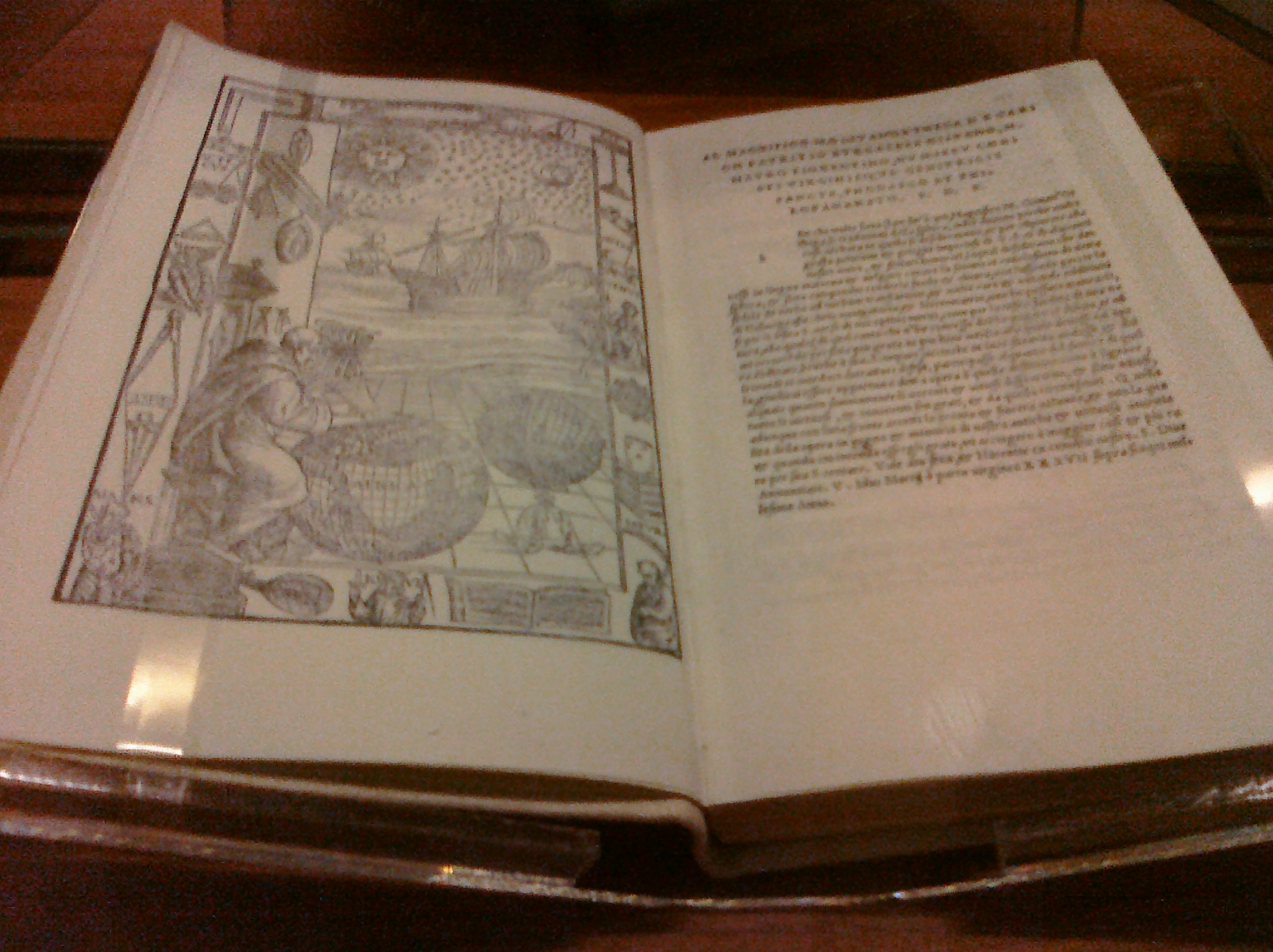

"Composition of the universe," dedicated to Cosimo I, showing a cosmographer at work.

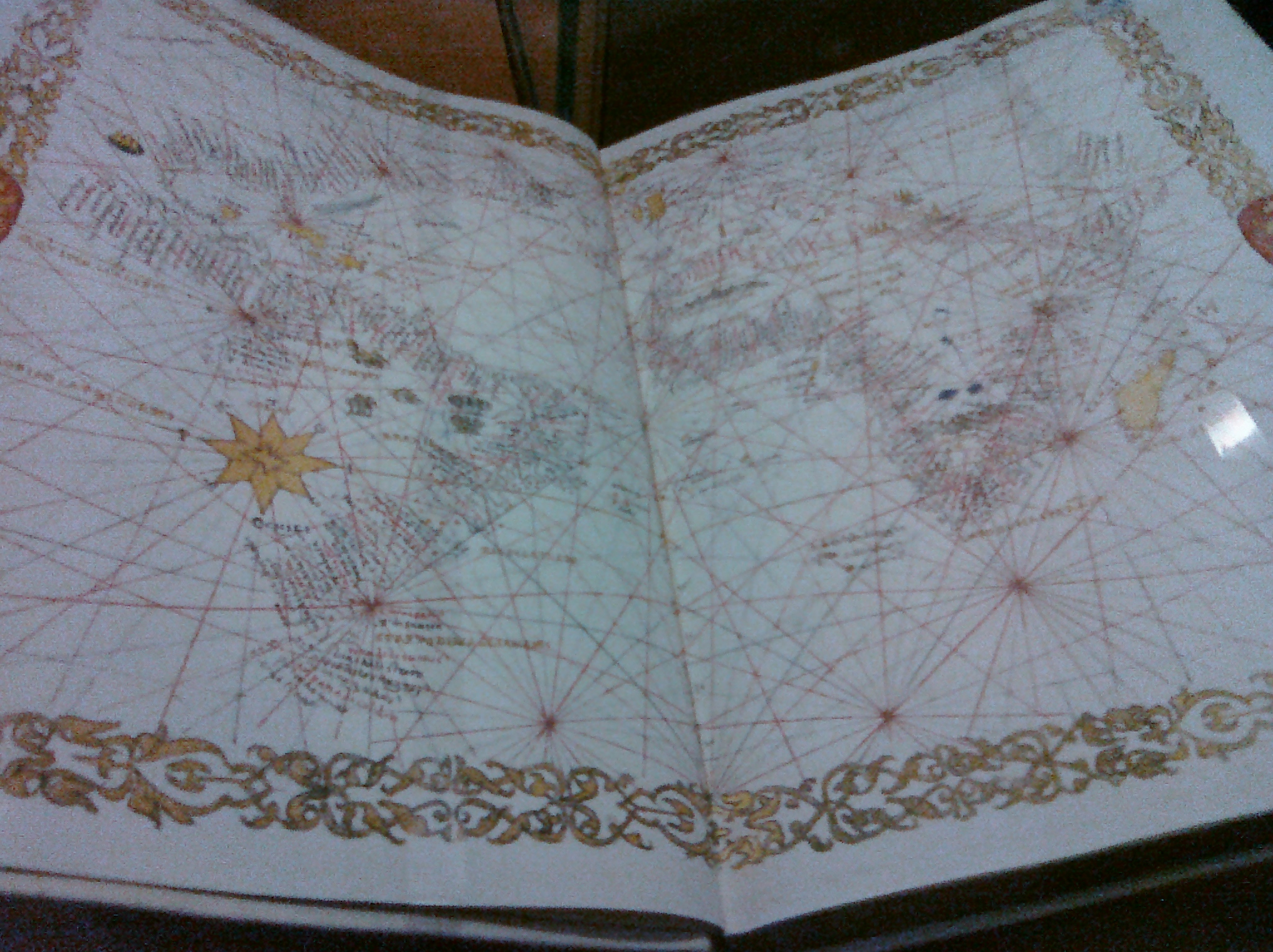

A nautical atlas. Fifteen watercolor plates portray the nautical maps and planispheres as well as the zodiac, armillary sphere and parts of the globe.

One scientific project Cosimo I commissioned was to turn the church of Santa Maria Novella into an astronomical observatory. The church wanted to reform the Julian calendar, so the church acquired instruments for observing solstices and equinoxes.

Scientific instrumentation wasn't just about function, as you can see in some of the above pictures. There was also beauty, an art form, involved. Bet you haven't seen one of these in a lab, holding kim-wipes or nitrile gloves.

Box for holding scientific instruments.

The picture isn't of the best quality, but it is so cool I had to share. It's a refraction dial, and worked with the cup (which had a lid) full of water.

The famed telescope....

...and up close.

1 If you've been to Rome or Florence, you've directly benefited from the genius supported by the Medicis: Brunelleschi, Botticelli, Donatello, Fra Angelico, Michelangelo, da Vinci; the Uffizi, Boboli Gardens, portions of the Vatican. Just a smattering of what they did for these places.

2 The exhibit was wonderful. Some of the exhibit visitors were not. For example, cell phone audio self-guided tours should be outlawed. As should people who are CLEARLY not interested in seeing the items (i.e. a gaggle of bored-to-tears teenage girls being literally dragged by their mother), given that they huddle in swarms around the exhibit and block your view and drone on about inane subjects in high-pitched valley girl voices. I'm just throwing that out there.

Comments