Males of many species guard the females they have mated with, a behavior generally interpreted as a tactic to reduce the likelihood that rival males will mate with the female. This, of course, can lead to a conflict between the sexes: where females might want to mate with other males, males will try to prevent this. In this case, the male-female association is based on conflict.

A new study on crickets (Gryllus campestris, see figure 1), however, suggests that the foundation of the couple’s association might be based on cooperation. By continuously monitoring natural cricket populations with marked individuals, the researchers were able to observe behaviors and predation.

Figure 1: The field cricket, G. campestris.

(Source: Wikimedia Commons, user: Roberto Zannon)

This allowed the researchers to show that:

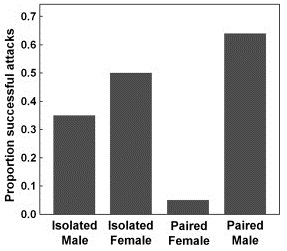

- When in a couple, male crickets use the (shared) burrow differently. They tend to place themselves farther from the entrance, allowing females to enter the burrow first in case of danger. This is shown to greatly increase the predation risk for males (see figure 2).

Figure 2: The proportion of successful predator attacks, in relation to sex and association status.

(Source: Rodríguez-Muñoz, Bretman and Tregenza, 2011)

- After mating, the males stay around for a longer time period and are more successful in fighting rival males.

- Males that stay longer get to mate more and increase their paternity of the female’s offspring.

- While the males are able to block the entrance of the burrow, and so force the female to stay, they do not limit the movement of their partner. Females appear to have free choice of whether to stay with the male, or to leave.

The authors propose that by staying with a male, the female gains two benefits:

Females gain two potential benefits from remaining with a male: first, they can use it to bias paternity in favor of that male by mating repeatedly with him, and second, they reduce their chances of being predated. Both of these have been shown to increase fitness in female crickets.

So, the authors see an alternative way for the development of mate guarding, besides conflict:

We suggest that mate guarding can evolve in two different ways, depending on a species’ life history. It can evolve through sexual conflict, driven solely by male benefits, if males can enforce female monandry through a predictable and/or short duration of the fertile period and the possibility of preventing female remating during that period. When enforcement is not possible or is too costly, for instance when there is a long fertile period or one that is under female control, guarding can evolve providing it also carries benefits for the female. In these situations, females can drive the evolution of cooperative mate guarding in a context of mutual benefit.

The study concludes:

Our study shows that mate guarding can involve cooperation between the sexes and that field-based studies are an important counterpoint to laboratory experiments. The understanding of mate guarding in general may benefit from an approach that accounts for the benefits and costs to both sexes and gives full consideration to both conflict and cooperation scenarios.

Reference

Rodríguez-Muñoz, R.; Bretman, A. and Tregenza, T. (2011). Guarding Males Protect Females from Predation in a Wild Insect. Current Biology. Published online 6 October. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.08.053.

Comments