Some of the craters surmounting the larger islands are of immense size, and they rise to a height of between three and four thousand feet. Their flanks are studded by innumerable smaller orifices. I scarcely hesitate to affirm that there must be in the whole archipelago at least two thousand craters. These consist either of lava and scoriæ, or of finely-stratified, sandstone-like tuff. Most of the latter are beautifully symmetrical; they owe their origin to eruptions of volcanic mud without any lava: it is a remarkable circumstance that every one of the twenty-eight tuff-craters which were examined had their southern sides either much lower than the other sides, or quite broken down and removed. As all these craters apparently have been formed when standing in the sea, and as the waves from the trade wind and the swell from the open Pacific here unite their forces on the southern coasts of all the islands, this singular uniformity in the broken state of the craters, composed of the soft and yielding tuff, is easily explained.

Considering that these islands are placed directly under the equator, the climate is far from being excessively hot; this seems chiefly caused by the singularly low temperature of the surrounding water, brought here by the great southern Polar current. Excepting during one short season very little rain falls, and even then it is irregular; but the clouds generally hang low. Hence, whilst the lower parts of the islands are very sterile, the upper parts, at a height of a thousand feet and upwards, possess a damp climate and a tolerably luxuriant vegetation. This is especially the case on the windward sides of the islands, which first receive and condense the moisture from the atmosphere."

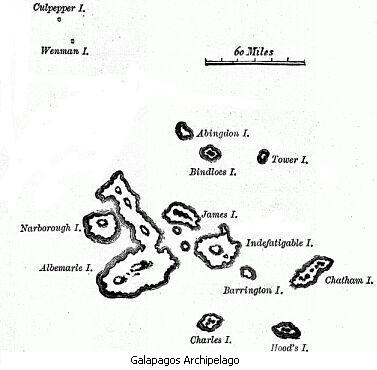

While the HMS Beagle was in the Pacific Ocean surrounding the Galapagos Islands, there had to be almost certainly a "luxuriant vegetation" in the form of phytoplankton, floating microscopic plants or algae. Here is a satellite image of these islands, in the black patches, on October 31, 1983, a time for strong spring time bloom.

This satellite image, courtesy of the US public, shows the westward transport of the phytoplankton plume for hundreds of miles by the South Equatorial Current (SEQ). Note the high levels of chlorophyll in areas marked in red. The SEQ, or in Darwin's language "the great southern Polar current," carries nutrients as it flows past the volcanic Galapagos Islands and spreads them westward along with the bloom. During photosynthesis, chlorophyll absorbs light energy thus phytoplankton synthesizes carbohydrates from carbon dioxide and water.

Darwin did notice the "very sterile" lower land in the Galapagos Archipelago. Sea water analyses have confirmed since the 1980s that elemental iron (Fe) is the limiting nutrient in phytoplankton bloom process around the Galapagos Islands. In fact, today, some say that one kilogram of fine Fe particles, of about half micron size, can trigger as much as 100 tonnes of phytoplankton biomass production. The iron in the sediments around the islands and the volcanic rocks beneath the surface is considered to be the main source of the iron to bloom phytoplankton in the Galapagos plume.

This is the origin of the ocean fertilization with iron dust.

[1] Charles Darwin, M.A., F.R.S., Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology of the countries visited during the voyage round the world of H.M.S. Beagle under the command of Captain Fitz Roy, London, England (1913)

Comments