University of Arizona (UA) scientists have announced their success in genetically altering mosquitos to be immune to the single-celled parasite that causes malaria.

Professor of entomology Michaiel Riehle led the UA research team hoping to stop the spread of malaria worldwide by replacing wild mosquitoes with laboratory-bred swarms unable to act as vectors of the disease because they are completely resistant to infection by the organism called Plasmodium that causes it.

Their new research will be published July 15 in the journal Public Library of Science Pathogens.

Riehle's team designed a snippet of genetic code able to insert itself into the mosquito genome and injected it into mosquito eggs to be passed on to future generations. The scientists used a mosquito species that is an important vector on the Indian subcontinent, Anopheles stephensi.

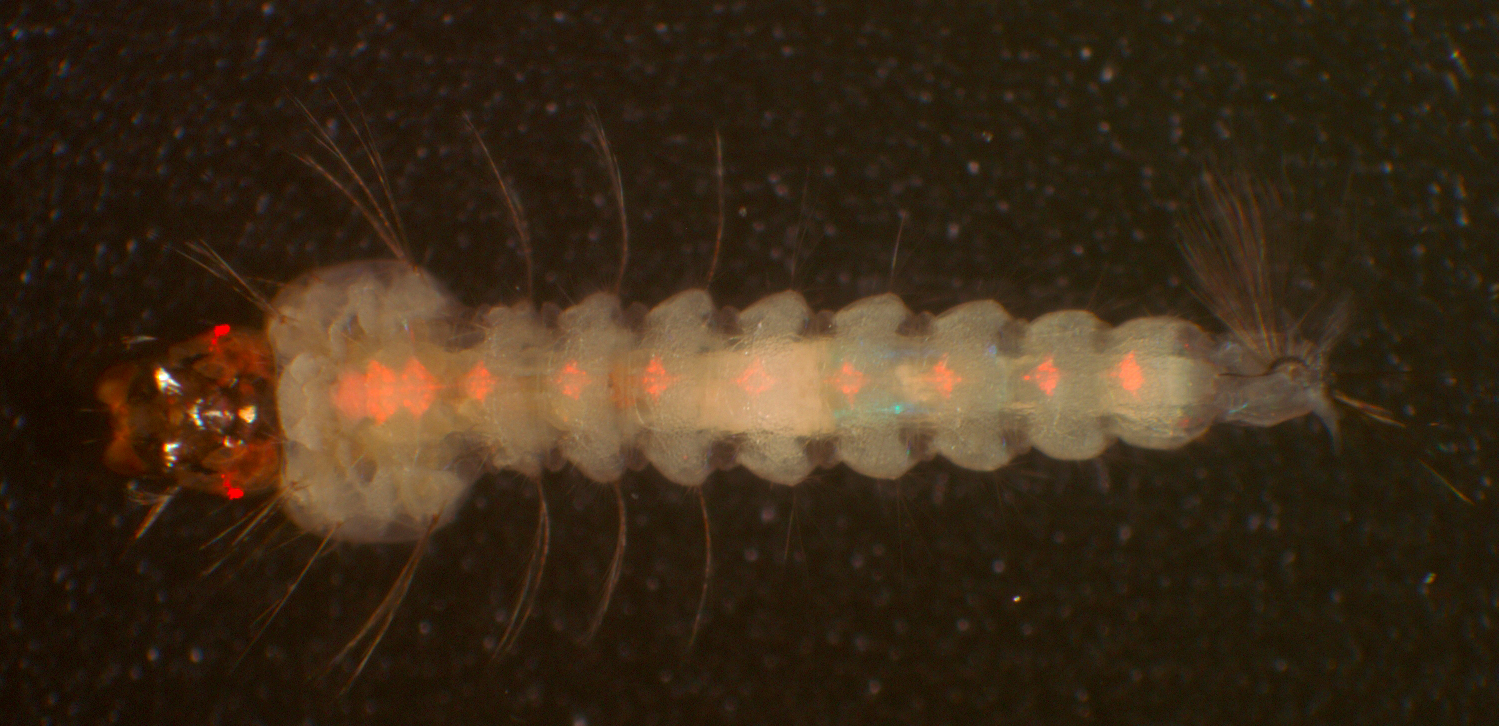

Photo: Mosquito larva under UV light, revealing a red fluorescent marker in its nervous system, causing eyes and nerves to glow, showing researchers this individual carries the genetic construct that makes it immune to the malaria parasite, by M. Riehle, University of Arizona

The researchers targeted one of the many molecular "on/off switches" controlling metabolic functions inside mosquito cells. The new genetic piece causes the signaling enzyme called Akt, a messenger molecule affecting larval development, immune response and lifespan to be continuously active.

Riehle and his co-workers then fed the genetically altered population malaria-infested blood and found the Plasmodium parasites had not infected any of the study mosquitoes.

According to background information in UA's press-release:

Approximately 250 million people contract malaria each year, and 1 million of them – mostly children – die of it. About ninety percent of the fatalities from malaria occur in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Every new malaria case starts with a bite from a mosquito belonging to one of the 25 species of the genus Anopheles that are significant vectors of the disease.

Riehle remarked, "If you want to effectively stop the spreading of the malaria parasite, you need mosquitoes that are no less than 100 percent resistant to it. If a single parasite slips through and infects a human, the whole approach will be doomed to fail."

Photo: A mosquito resting on a leaf, by Gerald Yuvallos on Flickr.com

My thoughts were buzzing about mosquitoes while I gardened because they were buzzing me, so the press-release about malaria-proof little blighters drew my attention.

Throughout Wisconsin, mosquitoes have a history of spreading Arboviral Encephalitides, though no cases have been reported recently.

A little more research confirms these wee winged pesterers are good for pollinating flowers (as they suck their life juices too) and getting gobbled in mass-quantities by birds, bats and fish.

More to read on the Net: How Malaria Works

Comments