A guy messes up his life, and the lives of those around him. We send him for rehabilitation: A jail term, AA meetings, community service, anger management classes, or restitution to victims.

An organization

messes up, and manages the crisis in well-accepted ways: Quick

communication from top managers, rapid assumption of responsibility, quick and

effective ameliorative action, ongoing transparency, and never for a moment

blaming the customers. As every management student knows, Johnson&Johnson set the gold

standard for crisis handling during the poisoned Tylenol episode. J&J’s good reputation

was quickly restored.

Other companies mismanage a customer uprising (for example, the Netflix pricing screw-up). Still others have committed their offense before modern crisis management principles were understood – or at a time when customer mores and expectations differed from today’s. For instance, Brown University was founded using profits from the slave trade. 250 years later, Brown University President Ruth Simmons appointed a Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice investigating the matter and recommending rehabilitative actions for the university.

What can rehabilitate these organizations in the long term?

The research and practice literature is rife with advice on short-term crisis management, but spare on the question of long-term rehabilitation for re-establishment of trust. Not surprising, as crisis management rightly emphasizes rapid action immediately following the offense, and today’s managers in general suffer from short-termism. The long term is important, though, so let’s see what can be said about it.

Looking for data on organizational rehabilitation, I find a remarkable range of actions, inactions, fumbles, and consequences.

- Following the 2009 crash, Wall Street banks did little to repent, or even change their practices. Their reputations are in the toilet, but their profits continue unabated.

- Kent State University built a parking lot – a parking lot! – over the site where US National Guardsmen shot and killed four students in 1970. Was this simple obtuseness, or an attempt to literally pave over and forget the incident? If the latter, it didn’t work; Neil Young’s song about the tragedy still plays on the radio today. Students still enroll at KSU. A lot of other people shun the place, having seen no sincere efforts toward rehabilitation. On the contrary, a schoolteacher in Ohio was recently fired for teaching, against his principal’s orders, the history of the Kent State incident. (Here’s what was done to rehab Jackson State, site of a similar shooting.)

- The core meltdown at Three Mile Island was the first major nuclear accident near major population centers. A federal review panel identified the shortcomings in training that led to operators’ wrong responses to the reactor’s indicators and gauges. This improved training at other sites, and generally improved performance of nuclear generators in the US and elsewhere. Little animosity remains toward First Energy Company of Akron, the owners of the TMI plant. However, the TMI experience made the public less forgiving of subsequent reactor failures. We tend to believe that lessons offered should be lessons learned. The Fukushima plant thus faces a long and uncertain road toward rehabilitation.

- The meltdown at Chernobyl was blamed on reactor design, not operator training. Nearby residents got sick or lost their homes as humans were banned from the vicinity. The upside was that Russia gained a large nature preserve, and much has been learned about impact of irradiation on animal species. Public reaction? People say, that’s Russia, and shrug.

- This year the Chonghaejin Marine Company’s Sewol ferry sunk, killing 300, mostly school children. The company’s president went into hiding and his children fled the country. A long list of prior code violations came to light. Meanwhile, the Korean Coast Guard’s response was pitifully inadequate. South Korea President Park Geun-Hye dissolved the Coast Guard (though everyone knows a reconstituted Guard would have to hire many of the same people), and the country’s Prime Minister resigned. The sinking of the ferry was the greatest domestic disaster in South Korea’s postwar history. Chonghaejin has no hope of rehabilitation. Despite the anger directed at President Park, however, the New York Times sees no long term impact on her ability to govern the nation.

- How will Ferguson, Missouri, rehabilitate itself? Given the behavior of police, the DA and residents, the town will draw few tourists or in-migrants for many years to come. The past few days have brought rumbles that the case may be re-opened. This offers a ray of hope for the town.

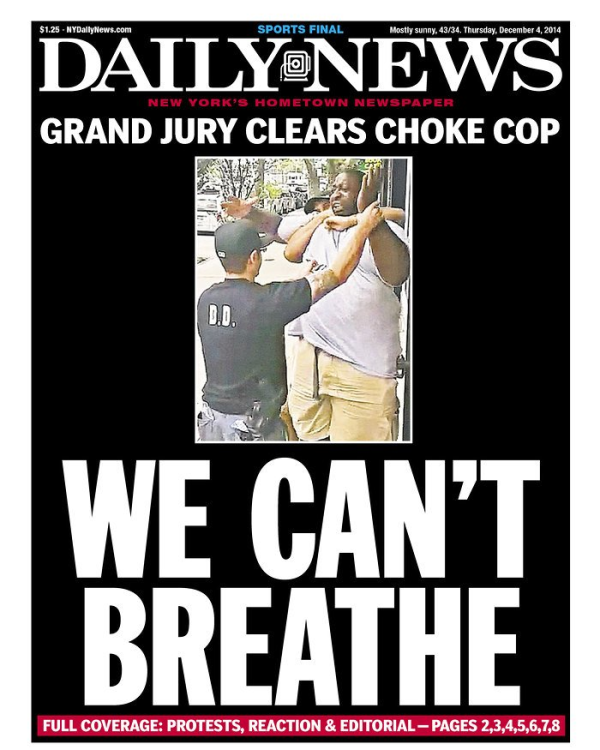

- And then, New York. Its Mayor voiced

disagreement with the court’s Eric Garner decision, and approved

protestors’ constitutionally guaranteed right to assemble. In return, the

police union members histrionically turned their backs on him – thus proving the

protestors’ point that your civil rights are of little concern to the

NYPD. I don’t want to visit New York any mo

re, but others will, of course,

because it’s… New York. (In my view, the separation of powers principle

says it’s the Mayor’s prerogative and duty to state his disagreement with

the courts, even if doing so risks violent public response - which the Mayor should also take pains to discourage and prevent. It’s also the

Mayor’s job, not the police’s, to consider impacts on tourism revenue, so

naturally his decisions will not always please the police union. You may

disagree with my parenthetical political analysis, but still agree that

rehabilitation is an issue here. On the personal level, the families and

colleagues of the slain police officers have all my sympathy.)

re, but others will, of course,

because it’s… New York. (In my view, the separation of powers principle

says it’s the Mayor’s prerogative and duty to state his disagreement with

the courts, even if doing so risks violent public response - which the Mayor should also take pains to discourage and prevent. It’s also the

Mayor’s job, not the police’s, to consider impacts on tourism revenue, so

naturally his decisions will not always please the police union. You may

disagree with my parenthetical political analysis, but still agree that

rehabilitation is an issue here. On the personal level, the families and

colleagues of the slain police officers have all my sympathy.)

- It took two generations to rehabilitate Germany. This year sees a menorah together with a Christmas tree at the Brandenburg Gate.

The reader can think of many, many more such examples. They will include the Tuskegee experiments, and torture at Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo.

Constructive responses to date have been situational. Examples are Brown University, the rehab of the US Secret Service, and the Federal Reserve’s initiative to restore trust in banks. Can there be a general theory of institutional rehabilitation? The cases above suggest the dimensions researchers must consider:

- The magnitude of losses and the perceived extent of betrayal.

- The extent to which people feel, if it happened to these victims, it could happen to me.

- The remaining attractions and good qualities of the offending organization.

- Expected time to rehabilitation, which might exceed the natural life spans of the culprits.

- The perception that the true culprits have been truly punished. No symbolic resignations, no golden parachutes, no get out of jail free cards, and no fall guys.

- Whether the organization’s practices have truly changed. Whether the changes truly reduce danger and increase fairness – as opposed to changes that simply reflect empty political correctness.

- Evidence of the organization’s ongoing self-examination.

A

related question is that of organizations that suffer (or cause) a slow erosion

of trust, rather than a sudden crisis. See, for example, my blog and many other recent

articles about the tech industry betraying its early promise, gradually losing its initially cultish customer base. Will the needed rehab be of the same nature, or different?

Comments