An extraordinary advance in human origins research reveals evidence of the emergence of the upright human body plan over 15 million years earlier than most experts have believed. More dramatically, the study confirms preliminary evidence that many early hominoid apes were most likely upright bipedal walkers sharing the basic body form of modern humans.

The report is based on research from Harvard University’s Museum of Comparative Zoology and from the Cedars Sinai Institute for Spinal Disorders that connects several recent fossil discoveries to older fossils finds that have eluded adequate explanation in the past.

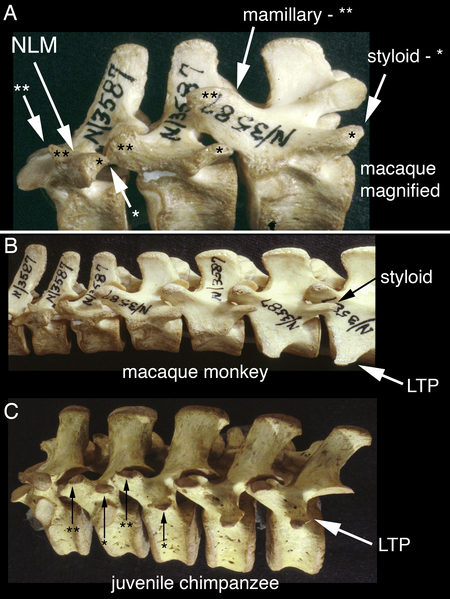

Recent advances in the field of homeotic genetics together with a series of discoveries of hominoid fossils vertebrae now strongly suggest that a specific genetic change that generated the upright bipedal human body form may soon be identified. The various upright “hominiform” hominoids appear to share this morphogenetic innovation with modern humans. Homeotics concerns the embryological assembly program for midline repeating structures such as the human vertebral column and the insect body segments.

The report analyses changes in homeotic embryological assembly of the spine in more than 200 mammalian species across a 250 million year time scale. It identifies a series of modular changes in genetic assembly program that have taken place at the origin point of several major groups of mammals including the newly designated ‘hominiform’ hominoids that share the modern human body plan.

The critical event involves a dramatic embryological change unique to the human lineage that was not previously understood because the unusual human condition was viewed as “normal.”

“From an embryological point of view, what took place is literally breathtaking,” says Dr. Aaron Filler, a Harvard trained evolutionary biologist and a medical director at Cedars Sinai Medical Center’s Institute for Spinal Disorders. Dr. Filler is an expert in spinal biology and the author of three books about the spine – “Axial Character Seriation in Mammals” (BrownWalker 2007), “The Upright Ape” (New Page Books 2007), and “Do You Really Need Back Surgery” (Oxford University Press 2007).

serial homology.png)

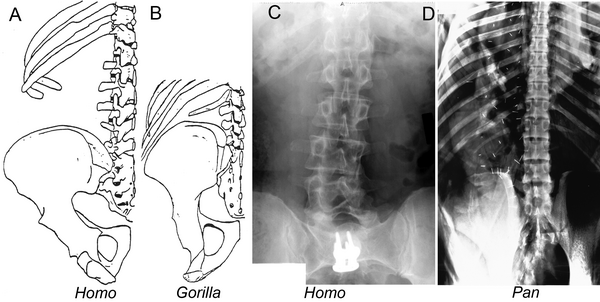

In most vertebrates (including most mammals), he explains, the dividing plane between the front (ventral) part of the body and the back (dorsal) part is a “horizontal septum” that runs in front of the spinal canal. This is a fundamental aspect of animal architecture. A bizarre birth defect in what may have been the first direct human ancestor led to the “transposition” of the septum to a position behind the spinal cord in the lumbar region. Oddly enough, this configuration is more typical of invertebrates.

The mechanical effect of the transposition was to make horizontal or quadrupedal stance inefficient. “Any mammal with this set of changes would only be comfortable standing upright. I would envision this malformed young hominiform – the first true ancestral human – as standing upright from a young age while its siblings walked around on all fours.”

The earliest example of the transformed hominiform type of lumbar spine is found in Morotopithecus bishopi an extinct hominoid species that lived in Uganda more than 21 million years ago. “From a number of points of view,” Filler says, “humanity can be redefined as having its origin with Morotopithecus. This greatly demotes the importance of the bipedalism of Australopithecus species such as Lucy (Australopithecus afarensis) since we now know of four upright bipedal species that precede her, found from various time periods on out to Morotopithecus in the Early Miocene.”

Citation: Filler AG (2007) Homeotic Evolution in the Mammalia: Diversification of Therian Axial Seriation and the Morphogenetic Basis of Human Origins. PLoS ONE 2(10): e1019. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001019

Comments