And so, we are left with kind of an 80/20 rule, the Pareto principle which posits that 20 percent of the causes for a given event are responsible for 80 percent of the outcomes.

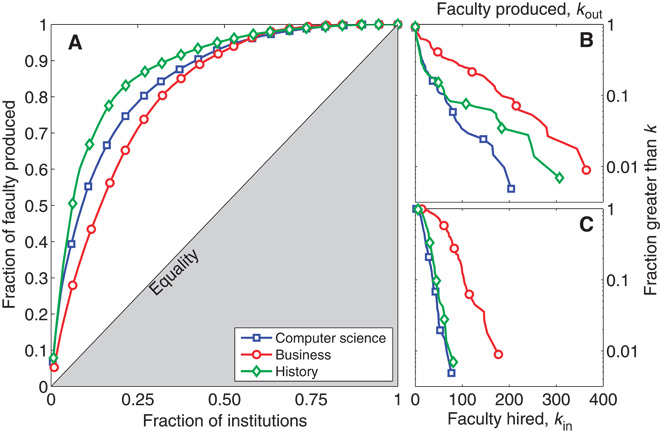

In this case, your school name and getting that Holy Grail of academia, a faculty job. Data on the educational histories of 19,000 current faculty members in three disciplines at hundreds of doctoral degree-granting institutions across the country found that 25 percent of doctoral degree-granting institutions across the country produce up to 86 percent of tenure-track faculty, down to as low as 71 percent, depending on the field.

Still, pretty clear.

And so overwhelming that it cannot be explained solely by a difference in educational quality between universities, according to a paper in Science Advances. Instead, the prestige of school names plays an important role in the faculty hiring process among alumni.

"We're not talking about a huge difference in quality between the top-10 institutions and the next 10," said Aaron Clauset, an assistant professor of computer science at University of Colorado at Boulder and lead author of the paper. "And yet, in terms of the ability to place people in tenure-track faculty positions, it is a huge difference."

The study also showed that the top 10 schools in each of the fields studied--computer science, business and history--produced between 1.6 and 3 times more faculty than the second tier of 10 schools and between 2.3 and 5.6 times more faculty than the third tier of 10 schools. The research team found that, on average, women graduating from the same elite institution as men had a more difficult time obtaining sought-after faculty appointments than their male counterparts.

Inequality in faculty production. (A) Lorenz curves showing the fraction of all faculty produced as a function of producing institutions. (B and C) Complementary cumulative distributions for institution out-degree (faculty produced) and in-degree (faculty hired). The means of these distributions are 21 for computer science, 70 for business, and 29 for history.

What about science academia? Government funding is certainly biased toward big names - Johns Hopkins University gets almost $600 million a year just from the National Institutes of Health - and while it isn't the case that science faculty is determined solely on ability to raise money from the government, a Johns Hopkins researcher is getting more resume reads than someone from Humboldt State University. There is also less bias against women in science. Women are actually over-represented in hiring in science, at least when they apply, it is just that many women PhDs instead venture into the corporate world, where family-friendly policies are more common.

For the analysis, institutions were ranked based on the faculty hiring networks themselves. An institution's prestige was calculated from its ability to hire candidates from better ranked programs and its ability to place its graduates in desirable faculty positions elsewhere.

"We're looking at evaluations of the output of a program," Clauset said. "When a Ph.D. goes out on the job market, other institutions evaluate how well that person's institution did in training them. The more people hired as faculty, and at more prestigious places, the more the community is saying the institution is doing a good job. By focusing on faculty hiring decisions, we're basically leveraging the experts in the field to make these program evaluations."

This output-based system of ranking institutions differs from more traditional rankings, like those used by U.S. News&World Report, which have been criticized for heavily relying on educational "inputs," such as standardized test scores and the financial investment made per student.

The ranking system created by Clauset and his colleagues better predicted the placement of doctoral graduates than either the U.S. News & World Report rankings or the National Research Council rankings.

Clauset first became interested in the factors that influence faculty hiring decisions when he was a graduate student at the University of New Mexico. He and two other doctoral students looked into what data were available to answer the question, but found there were none and let the question drop.

"We wondered who actually got hired into faculty jobs," Clauset said. "I think this is a pretty common question for doctoral students, since getting a Ph.D. is a major life investment, and many of us aspired to become faculty and have our own research groups."

Clauset picked the question back up after getting hired at CU-Boulder in 2010. He hired graduate students to collect data on three disparate academic disciplines. In all, the data collection effort took thousands of hours over several years.

"In addition to satisfying my own curiosity about these questions, our findings of systemic biases and fundamental hierarchies in faculty hiring provide a more clear picture of how academia works," Clauset said. "And the network-based technique we developed for ranking doctoral programs, which is based on expert evaluations of educational outcomes, provides a nicely data-driven approach to comparing institutions."

"These findings may help individuals who are contemplating a faculty career, and I hope they encourage a frank discussion more generally on whether the system is operating the way we want it to."

The study was funded in large part by the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation. Other co-authors of the study are Samuel Arbesman, of the Kauffman Foundation; and Daniel B. Larremore, of the Harvard School of Public Health.

Citation: Aaron Clauset, Samuel Arbesman, Daniel B. Larremore, Systematic inequality and hierarchy in faculty hiring networks, Science Advances Feb 1 2015 Vol. 1 no. 1 e1400005 DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.1400005

Comments