The objective of this study, undertaken by researcher Matthias S. Keil from the Basic Psychology Department of the UB and published in the prestigious US journal PLoS Computational Biology, was to ascertain which specific features the brain focuses on to identify a face. It has been known for years that the brain primarily uses low spatial frequencies to recognise faces. "Spatial frequencies" are, in a manner of speaking, the elements that make up any given image.

As Keil confirmed to SINC, "low frequencies pertain to low resolution, that is, small changes of intensity in an image. In contrast, high frequencies represent the details in an image. If we move away from an image, we perceive increasingly less details, that is, the high spatial frequency components, while low frequencies remain visible and are the last to disappear."

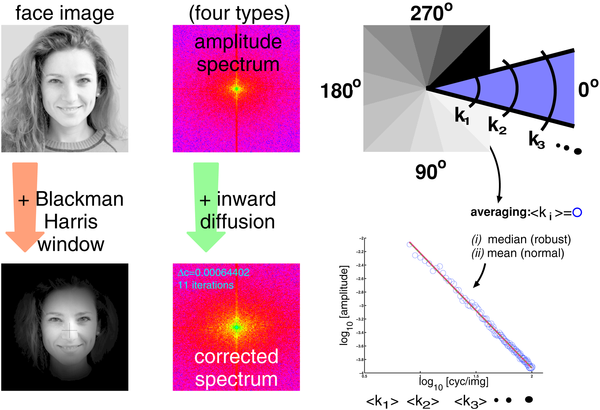

Computing slope values. The sketch summarizes the main steps that were taken in [20] for computing the slope values. Four types of spectra were considered (yielding four respective sets of slope values): (i) spectra of the original face images ( = raw), (ii) raw spectra corrected for truncation artifacts with inward diffusion ( = corrected raw), (iii) spectra of minimum 4-term Blackman-Harris (B.H.) windowed face images to suppress external face features [90], (iv) B.H. spectra corrected for the spectral “fingerprint” left by the application of the Blackman-Harris window. Now, in order to compute oriented slopes, a spectrum was subdivided into 12 pie slices (denoted by different shades of gray in the last image in the top row). Spectral amplitudes with equal spatial frequencies lie on arcs in the spectrum (schematically indicated by

As a result of the psychophysical research carried out prior to the publication of this study, it was known that the human brain was not interested in very high frequencies when identifying faces, despite such frequencies playing a significant role in, for example, determining a person's age. "In order to identify a face in an image, the brain always processes information with the same low resolution, of about 30 by 30 pixels from ear to ear, ignoring distance and the original resolution of the image," Keil says. "Until now, nobody had been able to explain this peculiar phenomenon and that was my starting point".

What Matthias S. Keil did was to analyse a large number of faces, namely those belonging to 868 women and 868 men. "The idea was to find common statistical regularities in the images." Keil used a model of the brain's visual system, that is, "I looked at the images to certain extent like the brain does, but with one difference: I had no preferred resolution, but considered all spatial frequencies as equal. As a result of this analysis, I obtained a resolution that is optimum in terms of encoding, as well as the signal-to-noise ratio, and was also the same resolution observed in the psychophysical experiments".

This result therefore suggests that faces are themselves responsible for our resolution preference. This led Keil to one of the brain's properties: "The brain has adapted optimally to draw the most useful information from faces in order to identify them. My model also predicts this resolution if we take into account the eyes alone – ignoring the nose and the mouth – but also by considering the mouth or nose separately, albeit less reliable."

Therefore, the brain extracts key information for facial identification primarily from the eyes, while the mouth and the nose are secondary, according to the study. According to Keil, if we take a photo of a friend as an example, one might think that every feature of the face is important to identify the person. However, numerous experiments have demonstrated that the brain prefers a coarse resolution, regardless of the distance between the face and the beholder. Until now, the reason for this was unclear. The analysis of the pictures of 868 men and 868 women in this study could help to explain this.

The results obtained by Kiel indicate that the most useful information is drawn from the images if they are around 30 by 30 pixels in size. "Furthermore, the pictures of the eyes provide the least 'noisiest' result, which means that they transmit more reliable information to the brain than the pictures of the mouth and the nose," the researcher said. This suggests that the brain's facial identification mechanisms are specialised in eyes.

This research complements a previous study published by Keil in PLoS ONE, which already advanced that artificial face identification systems obtain better results when they process small pictures of faces, which means that they could behave in this sense like humans.

Citation: Keil MS (2009) “I Look in Your Eyes, Honey”: Internal Face Features Induce Spatial Frequency Preference for Human Face Processing. PLoS Comput Biol 5(3): e1000329. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000329

Comments