A review from the University of Washington, Mid Sweden University and U.S. Forest Service may not make militant treehuggers happy but they can hash that out with climate change activists. The science shows many opportunities to use wood in ways that will displace products that cause a one-way flow of carbon dioxide from fossil fuel emissions to the atmosphere, contributing to the risk of global warming.

Sustainably managed forests are essentially carbon neutral as they provide an equal, two-way flow of carbon dioxide: the gas that trees absorb while growing eventually goes back to the atmosphere when, for example, a tree falls in the forest and decays, trees burn in a wildfire or a wood cabinet goes to a landfill and rots.

The co-authors write that the best approach for reducing carbon emissions involves growing wood as fast as possible, harvesting before tree growth begins to taper off and using the wood in place of products that are most fossil-fuel intensive, or even using woody biomass to produce biofuels for use in place of fossil fuels.

The authors aren't advocating that all forests be harvested in this way, just the ones we particularly want to use to help counter the buildup of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Older forests provide many needed ecological values even though their ability to absorb carbon dioxide slows down.

"Every time you see a wood building, it's a storehouse of carbon from the forest. When you see steel or concrete, you're seeing the emissions of carbon dioxide that had to go into the atmosphere for those structures to go up," said Bruce Lippke, University of Washington professor emeritus of forests resources, lead author of the paper in Carbon Management.

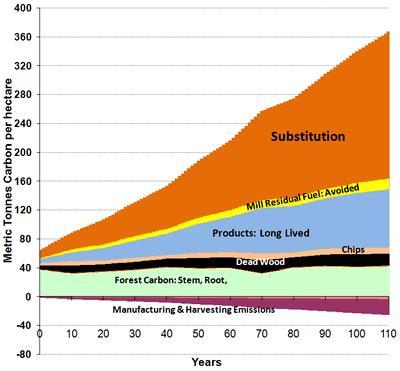

A Northwest state or private forest, harvested regularly for 100 years, helps keep carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere year after year by storing carbon in long-term wood products (blue) and by substituting wood for fossil-fuel-intensive products like steel and cement, thus avoids carbon dioxide emissions during their manufacture (orange). The chart also shows carbon that remains in a sustainably managed and harvested forest (green and black); and an "emissions" line (cranberry) at the bottom, representing the energy to harvest and process wood, which is partly counterbalanced by the "mill residual" line (yellow) that represents mill wastes burned for energy in place of fossil fuels. (Photo Credit: E Oneil/U of Washington

"While the carbon in the wood stored in forests is substantial, like any garden, forests have limited capacity to absorb carbon from the atmosphere as they age," Lippke said. "And there's always a chance a fire will sweep through a mature forest, immediately releasing the carbon dioxide in the trees back to the atmosphere.

"However, like harvesting a garden sustainably, we can use the wood grown in our forests for products and biofuels to displace the use of fossil-intensive products and fuels like steel, concrete, coal and oil."

Lippke says tradeoffs are best revealed through life cycle analysis – sometimes called a cradle-to-grave analysis – that assesses environmental impacts for all stages of a product including materials extraction, energy for processing and manufacturing, product use and ultimate disposal. The UW and 13 other institutions have been involved in life cycle analysis of wood products for 15 years through the Consortium for Research on Renewable Industrial Materials, based at the UW.

Some of the longest-lived wood products are those used for housing and light industrial buildings, estimated to have a useful life of at least 80 years, the paper said. For every use of wood there are alternatives, for example, wood studs can be replaced by steel studs, wood floors by concrete slab floors and woody biofuels by fossil fuel.

Using life cycle analysis the researchers, for example, compared replacing steel floor joists with engineered wood joists, thereby reducing the carbon footprint by almost 10 tons of carbon dioxide for every ton of wood used. In another example, wood flooring instead of concrete slab flooring was found to reduce the carbon footprint by approximately 3.5 tons of carbon dioxide for every ton of wood used.

"There's really no way to make these comparisons – and get the right answer for carbon mitigation – without doing life cycle analysis," Lippke said.

Not fully applying life cycle analysis can lead to unintended consequences. For instance, narrowly looking just at the carbon lost when wood products are disposed of through burning or being sent to landfills, has led to incentives not to cut trees in the first place, Lippke says.

"What's missing in the analysis and policy making," he said, "is how much carbon dioxide can be kept out of the atmosphere by using wood products, instead of those that take lot of fossil fuels to produce."

The authors said that Sweden is far ahead of the U.S. in sourcing their energy needs by using wood after having adopted taxes on carbon emissions two decades ago. Two of the co-authors, Leif Gustavsson and Roger Sathre, are from Mid Sweden University; other co-authors are Elaine Oneil and Rob Harrison, UW forest resources; and Kenneth Skog, Forest Service's forest products laboratory.

Comments