New evidence gathered by NASA's MESSENGER spacecraft at Mercury solves an apparent enigma about Mercury's evolution.

The data indicate the tiny planet closest to the sun, only slightly larger than earth's moon, has shrunk up to 7 kilometers in radius over the past 4 billion years, much more than earlier estimates. Older images of surface features indicated that, despite cooling over its lifetime, the rocky planet had barely shrunk at all. But modeling of the planet's formation and aging could not explain that finding.

Paul K. Byrne and Christian Klimczak at the Carnegie Institution of Washington have led a team that used MESSENGER's detailed images and topographic data to build a comprehensive map of tectonic features. That map suggests Mercury shrunk substantially as it cooled, as rock and metal that comprise its interior are expected to.

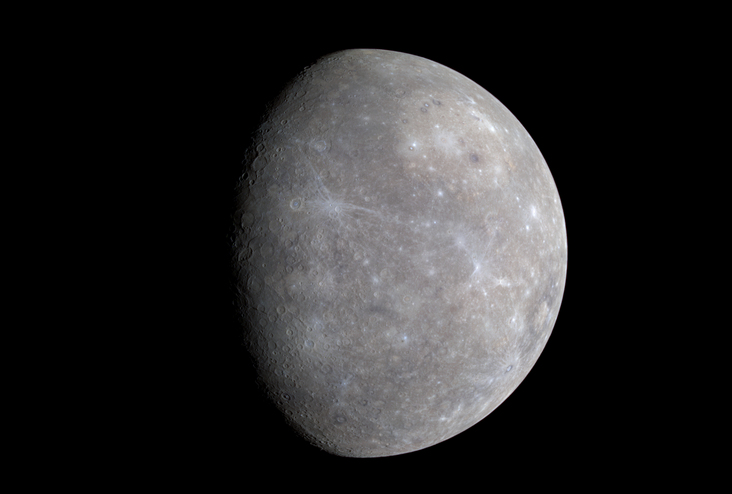

MESSENGER's Wide Angle Camera (WAC), part of the Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS), is equipped with 11 narrow-band color filters. As the spacecraft receded from Mercury after making its closest approach on 14 January 2008, the WAC recorded a 3x3 mosaic covering part of the planet not previously seen by spacecraft. The color image shown here was generated by combining the mosaics taken through the WAC filters that transmit light at wavelengths of 1000 nm (infrared), 700 nm (far red), and 430 nm (violet). These three images were placed in the red, green, and blue channels, respectively, to create the visualization presented here. The human eye is sensitive only across the wavelength range from about 400 to 700 nm. Creating a false-color image in this way accentuates color differences on Mercury's surface that cannot be seen in black-and-white (single-color) images. Color differences on Mercury are subtle, but they reveal important information about the nature of the planet's surface material. A number of bright spots with a bluish tinge are visible in this image. These are relatively recent impact craters. Some of the bright craters have bright streaks (called "rays" by planetary scientists) emanating from them. Bright features such as these are caused by the presence of freshly crushed rock material that was excavated and deposited during the highly energetic collision of a meteoroid with Mercury to form an impact crater. The large circular light-colored area in the upper right of the image is the interior of the Caloris basin. Mariner 10 viewed only the eastern (right) portion of this enormous impact basin, under lighting conditions that emphasized shadows and elevation differences rather than brightness and color differences. MESSENGER has revealed that Caloris is filled with smooth plains that are brighter than the surrounding terrain, hinting at a compositional contrast between these geologic units. The interior of Caloris also harbors several unusual dark-rimmed craters, which are visible in this image. The diameter of Mercury is about 4880 km (3030 miles). The image spatial resolution is about 2.5 km per pixel (1.6 miles/pixel). The WAC departure mosaic sequence was executed by the spacecraft from approximately 19:45 to 19:56 UTC on 14 January 2008, when the spacecraft was moving from a distance of roughly 12,800 to 16,700 km (7954 to 10377 miles) from the surface of Mercury. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington

"With MESSENGER, we have now obtained images of the entire planet at high resolution and, crucially, at different angles to the sun that show features Mariner 10 could not in the 1970s," said Steven A. Hauck, II, a professor of planetary sciences at Case Western Reserve University and the paper's co-author.

Mariner 10, the first spacecraft sent to explore Mercury, gathered images and data over just 45% of the surface during three flybys in 1974 and 1975. MESSENGER, which launched in 2004 and was inserted into orbit in 2011, continues collecting scientific data, completing its 2,900th orbit of Mercury later this month.

Mercury's surface differs from Earth's in that its outer shell, called the lithosphere, is made up of one tectonic plate instead of multiple plates.

To help gauge how the planet may have shrunk, the researchers looked at tectonic features, called lobate scarps and wrinkle ridges, which result from interior cooling and surface compression. The features resemble long ribbons from above, ranging from 5 to more than 550 miles long.

Lobate scarps are cliffs caused by thrust faults that have broken the surface and reach up to nearly 2 miles high. Wrinkle ridges are caused by faults that don't extend as deep and tend to have lower relief. Surface materials from one side of the fault ramp up and fold over, forming a ridge. The scientists mapped a total of 5,934 of the tectonic features.

The scarps and ridges have much the same effect as a tailor making a series of tucks to take in the waist of a pair of pants.

With the new data, the researchers were able to see a greater number of these faults and estimate the shortening across broad sections of the surface and thus estimate the decrease in the planet's radius.

They estimate the planet has contracted between 4.6 and 7 kilometers in radius.

"This is significantly greater than the 1 to maybe 2 kilometers reported earlier on the basis of Mariner 10 data," Hauck said.

And, importantly, he said, models built on the main heat-producing elements in planetary interiors, as detected by MESSENGER, support contraction in the range now documented.

One striking aspect of the form and distribution of surface tectonic features on Mercury is that they are largely consistent with some early explanations about the features of Earth's surface, before the theory of plate tectonics made them obsolete—at least for Earth, Hauck said.

So far, Earth is the only planet known to have tectonic plates instead of a single, outer shell.

The findings, therefore, can provide limits and a framework to understand how planets cool—their thermal, tectonic and volcanic history. So, by looking at Mercury, scientists learn not just about planets in our solar system, but about the increasing number of rocky planets being found around other stars.

Comments