Researchers at Duke University Medical Center have identified neurons in the songbird brain that convey the auditory feedback needed to learn a song. Their research, published in Neuron, lays the foundation for improving human speech, for example, in people whose auditory nerves are damaged and who must learn to speak without the benefit of hearing their own voices.

"This work is the first study to identify an auditory feedback pathway in the brain that is harnessed for learned vocal control," said Richard Mooney, Ph.D., Duke professor of neurobiology and senior author of the study. The researchers also devised an elegant way to carefully alter the activity of these neurons to prove that they interact with the motor networks that control singing.

An excess of a particular serotonin receptor in the center of the brain may explain why antidepressants fail to relieve depression symptoms for 50 percent of patients, indicates a new study published in Neuron.

The authors say the study is the first to find a causal link between receptor number and antidepressant treatment and may lead to more personalized treatment for depression, including treatments for patients who do not respond to antidepressants and ways to identify these patients before they undergo costly, and ultimately, futile therapies.

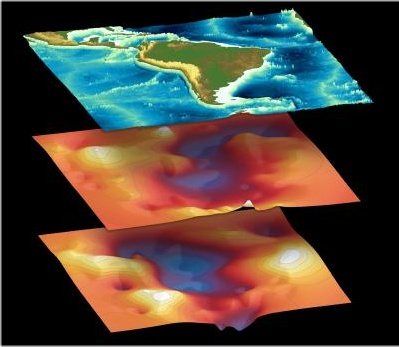

The disastrous magnitude 7.0 earthquake that triggered destruction and mounting death tolls in Haiti this week occurred in a highly complex tangle of tectonic faults near the intersection of the Caribbean and North American crustal plates, according to a geologist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI).

Jian Lin, a WHOI senior scientist in geology and geophysics, said that there were three factors that made the quake particularly devastating: First, it was centered just 10 miles southwest of the capital city, Port au Prince; second, the quake was shallow—only about 10-15 kilometers below the land's surface; third, and more importantly, many homes and buildings in the economically poor country were not built to withstand such a force and collapsed or crumbled.

While people typically blame incompetency when airport security screeners fail to keep dangerous weapons off airplanes or when doctors miss developing cancer tumors, the real culprit may be evolution, according to researchers at Harvard Medical School. Their new study published in Current Biology suggests that people simply haven't evolved superior skills for finding things that are rare.

"We know that if you don't find it often, you often don't find it," said Jeremy Wolfe of Harvard Medical School. "Rare stuff gets missed." That means that if you look for 20 guns in a stack of 40 bags, you'll find more of them than if you look for the same 20 guns in a stack of 2,000 bags.

The Tibetan Plateau—thought to be the primary source of heat that drives the South Asian monsoon—may have far less of an effect than moist, warm air insulated over continental India by the Himalayas and other surrounding mountains, say Harvard climate scientists writing this week in Nature.

The team says that understanding the monsoon's proper origin, especially in the context of global climate change, is crucial for the future sustainability of the region. The findings also have broad implications for how the Asian climate may have responded to mountain uplift in the past, and for how it might respond to surface changes in the coming decades, the researchers say.

Conservation efforts aimed at protecting Gorillas And Elephants in African parks and reserves are well intentioned but are often based on incorrect assumptions about the local culture, say Purdue University anthropologists. In a new Conservation Biology paper, the team says that understanding local human communities is key to protecting the wildlife they live alongside.

Study: Caloric Restriction In Humans And Aging

Study: Caloric Restriction In Humans And Aging Science Podcast Or Perish?

Science Podcast Or Perish? Type 2 Diabetes Medication Tirzepatide May Help Obese Type 1 Diabetics Also

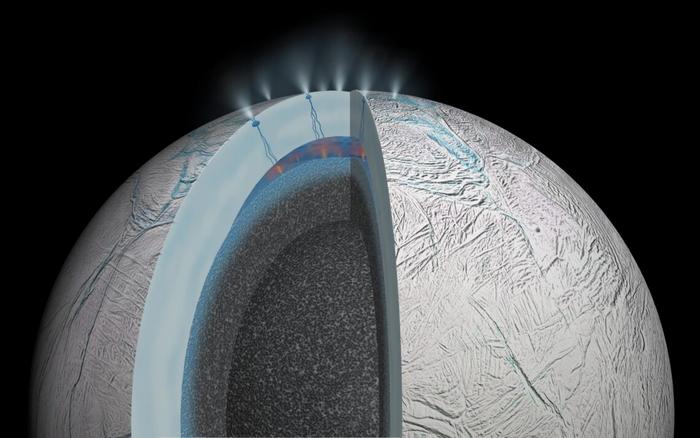

Type 2 Diabetes Medication Tirzepatide May Help Obese Type 1 Diabetics Also Life May Be Found In Sea Spray Of Moons Orbiting Saturn Or Jupiter Next Year

Life May Be Found In Sea Spray Of Moons Orbiting Saturn Or Jupiter Next Year