We read a lot about kids not being as good in science as we were back in the day. And we read a lot about women being missing from science too. You wouldn't know it by these outstanding young scientists in this year's EU contest for Young Scientists, which was held in Copenhagen, Denmark and rewarded contestants aged 14 - 19 who shared a €46,500 prize pot.

The contestants represented 39 countries across Europe - as well as special guests Brazil, Canada, China, Mexico, New Zealand and the USA - and they presented 87 winning projects from national competitions covering a wide range of scientific disciplines; from engineering and earth sciences to biology, mathematics, chemistry, physics, medicine, computer and social sciences. The standard of entries was consistently high and several past participants have achieved major scientific breakthroughs or set up businesses to market the ideas developed for the Contest.

"The EU Contest for Young Scientists is about supporting the rising stars of tomorrow's European science.” says European Science and Research Commissioner Janez Potocnik. It shows that Europe is a real reservoir of talents which is crucial at a time of global competition for knowledge. It also makes young people enjoy the experience of working together, beyond national borders, in the spirit of the European Research Area we strive to build.

Magdalena Bojarska from Poland - “Hamiltonian cycles in generalized Halin graphs”

Magdalena Bojarska from Poland - “Hamiltonian cycles in generalized Halin graphs”

Study: Caloric Restriction In Humans And Aging

Study: Caloric Restriction In Humans And Aging Science Podcast Or Perish?

Science Podcast Or Perish? Type 2 Diabetes Medication Tirzepatide May Help Obese Type 1 Diabetics Also

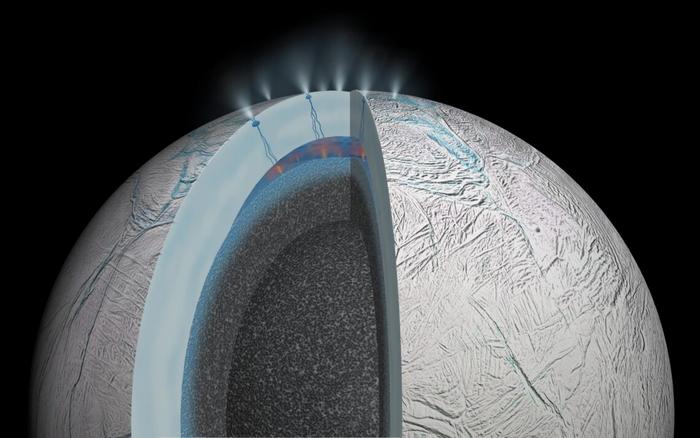

Type 2 Diabetes Medication Tirzepatide May Help Obese Type 1 Diabetics Also Life May Be Found In Sea Spray Of Moons Orbiting Saturn Or Jupiter Next Year

Life May Be Found In Sea Spray Of Moons Orbiting Saturn Or Jupiter Next Year