Opioid Addicts Are Less Likely To Use Legal Opioids At The End Of Their Lives

Opioid Addicts Are Less Likely To Use Legal Opioids At The End Of Their LivesWith a porous southern border, street fentanyl continues to enter the United States and be purchased...

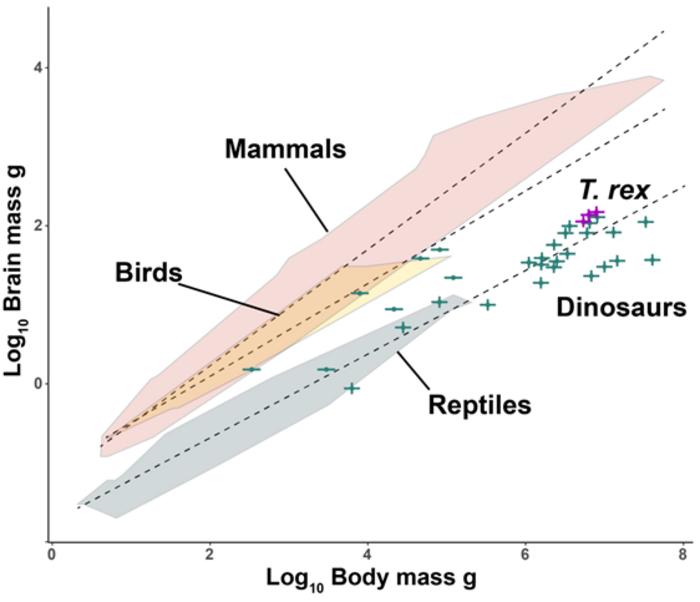

More Like Lizards: Claim That T. Rex Was As Smart As Monkeys Refuted

More Like Lizards: Claim That T. Rex Was As Smart As Monkeys RefutedA year ago, corporate media promoted the provocative claim that dinosaurs like Tyrannorsaurus rex...

Study: Caloric Restriction In Humans And Aging

Study: Caloric Restriction In Humans And AgingIn mice, caloric restriction has been found to increase aging but obviously mice are not little...

Science Podcast Or Perish?

Science Podcast Or Perish?When we created the Science 2.0 movement, it quickly caught cultural fire. Blogging became the...