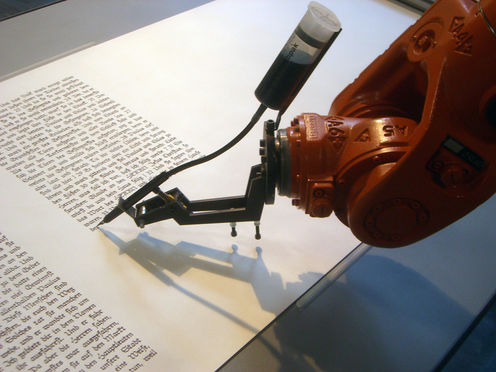

Not now! Roboscribe is busy creating a masterpiece (of heuristic analysis). gastev, CC BY

By Peter McOwan, Queen Mary University of London

The human race has long designed and used tools to help us solve problems, from flint axes to space shuttles. They affect our lives and shape society in expected and sometimes unexpected ways. We may understand how these tools work – after all, we built them – but sometimes it’s the use they’re put to that surprises.

Artificial intelligence is one such tool: software that mimics the way that natural intelligence functions. Like an information loom it weaves knowledge from data, spinning out patterns of behavior we identify as the action of intelligence. We have largely accepted living with machines that are faster, stronger, and able to go places and do things we can’t because of the benefits they bring. But smarter machines? Well that’s a different sort of challenge.

We don’t generally worry that our mobile phone’s calculator outstrips our arithmetic skills, nor that it can automatically connect to the best network base tower, or correct the spelling in our text messages. Nor are we bothered that the television is smart enough to tune itself to channels automatically.

These are the sort of tasks that humans could have performed in the past, laboriously, that our equipment now – due to elements of artificial intelligence – performs for us and makes our lives easier. We tend to think of AI as something embodied primarily in robots, rather than consumer goods. A view often reinforced by films and books – because it’s hard to portray a story’s protagonist dramatically if it’s simply thousands of lines of computer code.

Creative intelligence

However, many are sensitive to the idea of artificial intelligence being artistic – entering the sphere of human intelligence and creativity. AI can learn to mimic the artistic process of painting, literature, poetry and music, but it does so by learning the rules, often from access to large datasets of existing work from which it extracts patterns and applies them. Robots may be able to paint – applying a brush to canvas, deciding on shapes and colors – but based on processing the example of human experts. Is this creating, or copying? (The same question has been asked of humans too.)

The challenge for an artificial intelligence that attempts to write literature is the processing of language and semantics. While sophisticated systems like Apple’s Siri or Microsoft’s Cortana can react to basic spoken phrases, the ambiguity of meaning in language is difficult for a machine to learn.

Add to this the use of figures of speech, metaphor, and other cultural references, not to mention the characters, their speech and relationships and a coherent well paced story arc with the branching narrative twists and turns that are needed in a good novel, and we are arguably still some way from the first best-selling book totally written by a machine.

But would we want to produce AI able to write a novel that could pass as human, or to paint or compose music? There are talented humans who can do these things already. Smart tools to support human creativity are useful – our recent work on an AI to help magicians design new magic tricks is one example – so why replace the human entirely when you can work with the machine?

One argument for creative machine intelligences is that if we are to understand the human creative process, being able to mimic and test it against the real thing could reveal insight into how our brains work. Our technology fascination continues to strive for a better mousetrap, but would we want AI artists that were better than human? What would that mean, how would we know? Should AI art be similar or totally different to human art?

These are fascinating questions. If art can in any way be considered a tool, it’s a tool for helping us understand ourselves and our world better. There are rules to human art and literature even if they are sometimes broken, and if we can’t imagine our unimaginable, perhaps artificial artists can. Would that be a threat to art, or a provocative new form of artistic expression?

Perhaps, more than anything, what makes an artificially intelligent tool different is that rather than simply extending the physical, it arguably contains a part of us.

Peter McOwan, Professor of Computer Science at Queen Mary University of London, receives EPSRC, EU, and Royal Society funding.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Comments