Fire is central to the rise of human culture and a discovery by archeologists at Qesem Cave, a site near present-day Rosh Ha’ayin in the Central District of Israel, has pushed the date for unequivocal repeated fire building over a continuous period back a little farther - back to around 300,000 years ago.

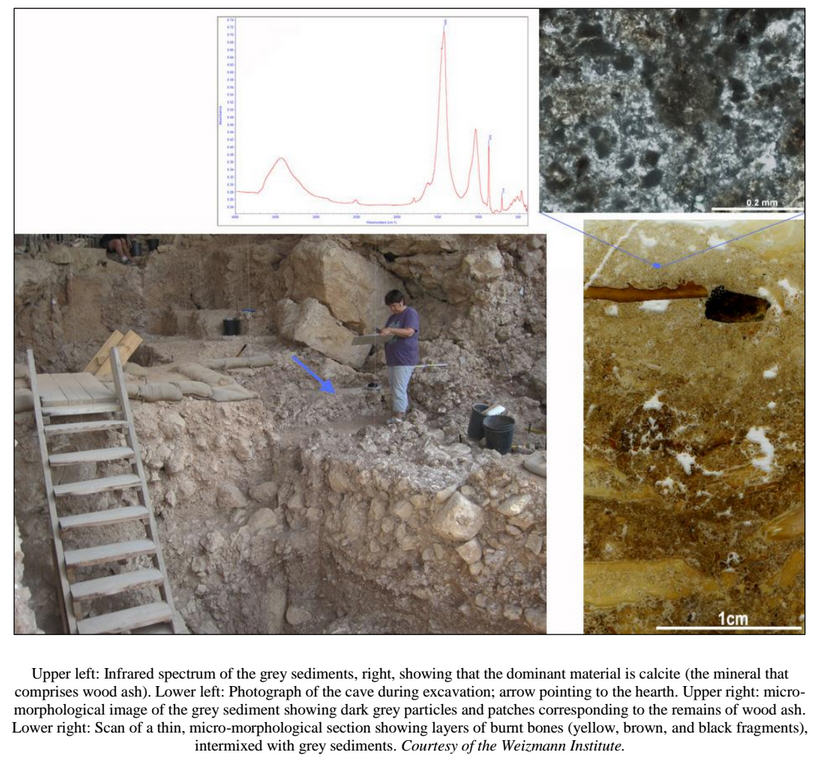

Clearly, these prehistoric humans already had a highly advanced social structure and intellectual capacity. Dr. Ruth Shahack-Gross of the Kimmel Center for Archeological Science at the Weizmann Institute of Science has been involved in the project since excavations began in 2,000 A.D., and identified a thick deposit of wood ash in the center of the cave. Using infrared spectroscopy, she and colleagues were able to determine that, mixed in with the ash, were bits of bone and soil that had been heated to very high temperatures. This was conclusive proof that the area had been the site of a large hearth.

They then tested the micro-morphology of the ash by extracting a cubic chunk of sediment from the hearth and hardening it in the lab. By slicing it into extremely thin slices – so thin they could be placed under a microscope to observe the exact composition of the materials in the deposit - they were able to see how they were formed. With this method, she was able to distinguish a great many micro-strata in the ash – evidence for a hearth that was used repeatedly over time.

Around the hearth area, as well as inside it, the archaeologists found large numbers of flint tools that were clearly used for cutting meat. In contrast, the flint tools found just a few meters away had a different shape, being designed for other activities. Also in and around the area were large numbers of burnt animal bones – further evidence for repeated fire use for cooking meat.

The researchers have detected the organization of various “household” activities in different parts of the cave points to an organization of space, and a thus kind of social order, that is typical of modern humans. This suggests that the cave was a sort of base camp that prehistoric humans returned to again and again.

“These findings help us to fix an important turning point in the development of human culture – that in which humans first began to regularly use fire both for cooking meat and as a focal point – a sort of campfire – for social gatherings,” Shahack-Gross says. “They also tell us something about the impressive levels of social and cognitive development of humans living some 300,000 years ago.”

The researchers think that these findings, along with others, are signs of substantial changes in human behavior and biology that commenced with the appearance in the region of new forms of culture – and perhaps a new human species – about 400,000 years ago.

Published in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

Comments