Though basic research is incredibly valuable, without applied results it has limited use for the public. And that means limited funding. The U.S. government spent $5 billion this century convincing young scholars that government-funded research was real research and they would have freedom and not be corporate controlled.

Their public relations campaign worked too well. Everyone wanted to stay in college, to such an extent that only 6 PhDs were competing for each job each year. Post-doctoral positions started to look like careers, and some positions even required you work for free. The government had created artificial demand and had no supply.

It's no surprise that younger researchers have not bought into the mythology that only government-funded research is real science. The impact has started to be felt in various biomedical fields, where new scholars simply go straight to industry. Stem cells are just one example but they are a telling one, because stem cells were used during the George W. Bush administration to drive a wedge between academics and the White House. President Bush was the first president to fund human embryonic stem cell research, but he limited it to existing lines that had been created outside federal funding. His political opponents called that a ban, California rushed to spend an additional $3 billion of taxpayer money, convinced that it would cure Parkinson's or other diseases.

The science never met the hype and now younger scholars are avoiding the field, partly because there doesn't seem to be a real benefit any time soon, partly because there is a glut of academics all competing for a finite pool of taxpayer money (and experienced scholars have an advantage in working the system), and partly because if it's going to be a benefit, it will be in industry.

Yet a new study published in Cell Stem Cell looking at how the National Institutes of Health awards R01 grants questions part of the explanation.

"From a policy and leadership perspective, one needs to understand what the near future year implications of an aging workforce are," says Misty L. Heggeness, an author of the study, which was conducted when she was a labor economist in the NIH Office of the Director. "If a system discourages younger cohorts from staying and is heavily composed of older cohorts who will exit the workforce in the near term, who will replace them?"

Government funding is the lifeblood of academia, and older scientists are better at working the system. They know failure is often a career-killer at review time, so they keep expectations modest, while younger scientists tend to think being bold is good.

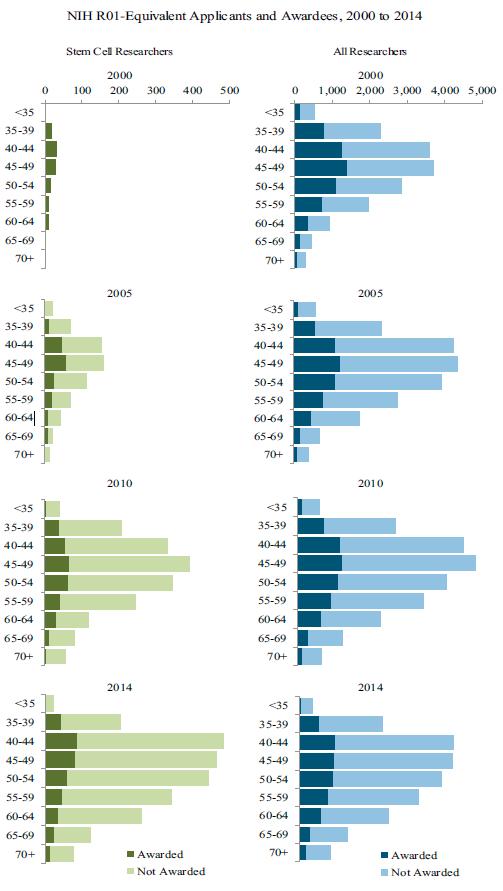

Heggeness and colleagues chose both to study the whole biomedical research field and to focus in on one subfield--the stem cell field--to see why more grants go to older researchers. The study authors reviewed biomedical R01 grant records from 1980 onward and the subset of stem cell grant applications from 2000 to 2014.

Indeed, significantly more NIH grants went to older applicants even though hESC research was new. Between 2005 and 2014, the number of R01 grants going to stem cell scientists aged 60-64 increased by 240 percent. During the same time period, grants going to scientists aged 40-44 increased 80.4 percent, and grants going to scientists aged 45-49 increased by 32.8 percent, according to the paper. And while competition for R01 grants for stem cell research increased since the early 2000s, there was no clear trend that favored older applicants. Both young stem cell scientists aged 35-39 and older scientists aged 60-69 saw an increase in acceptance rates during the study; from 18.4 to 21.6 percent and 16.3 to 20.9 percent, respectively. However, applicants aged 50-60 saw their acceptance rates decline during the study.

NIH accepted grant proposals from younger applicants at roughly the same rate as it accepted grant proposals from older applicants--there was just an outsized number of older researchers applying to grants.

If a preference for older applicants was not directly contributing to the graying of the biomedical workforce, the authors conclude that a host of other factors must be at play, including changes in how academics are trained and paid.

"The fact of the matter is that to apply for an NIH grant, one needs to be affiliated with an institution," says Heggeness. "If people are receiving tenure track positions later in life today than two or three decades ago--or if younger scientists are moving into the private sector and not applying for NIH grants--that influences the average age of recipients of a first NIH R01-equivalent grant."

Comments