TV presenter Michael Mosley was the main exhibit in a public experiment at the Science Museum in London, exploring the inside story of the human digestive system. He swallowed a mini camera in a pill that took photographs three times a second as it passed through his gut.

As it passed through his stomach, he related the story of how William Beaumont (1785–1853), U.S. Army surgeon, the “Father of Gastric Physiology”, who did experiments while treating Alexis St. Martin, a Canadian voyageur working as an employee of a fur company on Mackinac Island (Michigan),who had been accidentally shot in the stomach with buckshot. Dr. Beaumont treated his wound, but expected St. Martin to die from his injuries, but St. Martin survived with a hole, or fistula, in his stomach that never fully healed. Unable to continue work for the American Fur Company, he was hired as a handyman by Dr. Beaumont.

Most of the experiments were conducted by tying a piece of food to a string and inserting it through the hole into St. Martin’s stomach. Every few hours, Beaumont would remove the food and observe how well it had been digested. Beaumont also extracted samples of gastric acid from St. Martin’s stomach for analysis, and for experiments in which he used it to “digest” bits of food in cups. This led to the important discovery that the stomach acid, and not solely the mashing, pounding and squeezing of the stomach, digests the food into nutrients the stomach can use; in other words, digestion was primarily a chemical process and not a mechanical one. (condensed from Wikipedia)

While still with the stomach, we switched to the experience of a gastric bypass patient. It appears that the procedure does not simply reduce — drastically — the amount of stomach into which one can stuff food, but also isolates and renders inactive that part of the stomach which produces ghrelin, the ‘hunger hormone’.

Towards the end of the programme, the pill had found its way to the colon. In a separate take, Mosley went to a very smelly laboratory where his stool bacteria were being cultured, and where we learned about research into faecal transplants at Imperial College, London increasingly used to treat people with serious stomach and bowel disorders. For people with severe intestinal problems which do not yield to prebiotics, probiotics, or medications, the hope is that cultured faecal bacteria of the ‘right’ sort can be introduced through a stomach tube (why not at the other end?)

However, in the middle, namely the small intestine, came the most profound (to me) part of the programme, where we were introduced to the gut’s own nervous system, with the information that there are as many neurons in the human intestine as in the brain of cat.

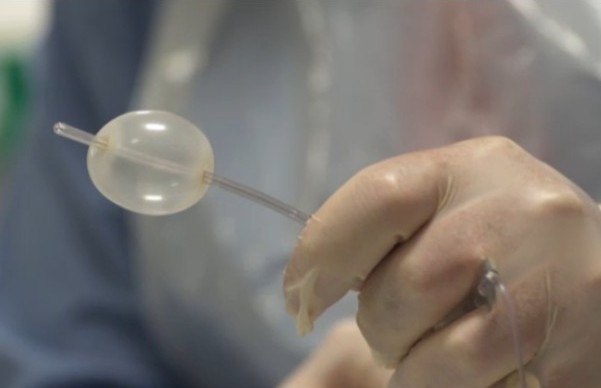

After filling in an online personality type questionnaire, Mosley went to the Wingate Institute of Neurogastroenterology to visit Dr Adam Farmer, a Consultant Gastroenterologist whose research field includes Human Psychophysiological Responses to Visceral and Somatic Pain. He has shown significant differences in the responses to gut part between extraverts (note spelling!) and people with a neurotic personality (why not introverts, à la original classification by Carl Jung?) Mosley sat back, and a tube was inserted into his oesophagus. Pain was administered by blowing up the pictured balloon on the tube. It was not a pleasant experience, judging by the sight of Mosley squirming on the couch.

The classical, textbook idea is that heart rate and blood pressure should both increase in response to pain. However, Adam Farmer’s research is showing that in neurotics, they actually show a transient decrease, which he attributes to a possible pain control mechanism mediated by the vagus nerve. With Michael Mosley — who describes himself as a neurotic posing as an extravert (presumably for professional reasons) — heart rate and blood pressure dropped for about two seconds. Farmer suggested that treating severe gut pain in the two kinds of patients might involve different approaches, for the neurotic patients a psychological approach such as cognitive behaviour therapy, with extraverts a pharmacological one.

I am left wondering if such deep-seated differences between the two personality types also have implications extending far beyond the alimentary canal.

(Note: front page picture, from Wikimedia Commons, is labelled in Icelandic)

Comments