In the Iowa Gambling Task, a participant is presented with four, facedown decks of cards. He or she can flip over cards from any deck. Most cards earn a reward and some cards incur a penalty. Of the four decks, some are better (contain more reward-earning cards) than others.

In the Iowa Gambling Task, a participant is presented with four, facedown decks of cards. He or she can flip over cards from any deck. Most cards earn a reward and some cards incur a penalty. Of the four decks, some are better (contain more reward-earning cards) than others.Over time, participants should learn which decks are best and start flipping cards only from the highest-paying decks. The test is thought to measure the emotional component of learning, or intuition—based on reward and punishment, participants begin to "feel" which decks are best and worst.

Admittedly this is cool in itself and could be the backbone of a couple month's worth of blog posts. But delving deeply into background and methodology is so yesterday—instead, here for the Twitter/iPad/Hulu brain are sound byte highlights of the many, many cool things that've been done with the test:

• Most healthy participants take between 40 and 50 flips to recognize good and bad decks and then stick to the good ones. But galvanic skin tests, like those of a lie detector, show that after only about 10 flips, participants start to show stress responses as their hands hover above bad decks. We know a bad deck before we're aware of it.

• The orbitofrontal cortex processes the emotion of reward and punishment as it relates to decision-making. When you wince after a bad choice, that's the orbitofrontal cortex at work. People with brain damage in this region, while cognitively unimpaired, are devoid of the emotions of good and bad choices. And they show no galvanic skin response to impending bad choices on the Iowa Gambling Task. In fact, these people will sometimes continue to choose cards from bad decks long after they're aware that they're losing money.

• Dumber is better. It turns out that a college education is predictor of poorer performance on the Iowa Gambling Task. Though unproven, most people think this effect is due to higher education’s emphasis on rational decision-making at the expense of emotion-based decisions. In other words, college squashes our intuition. Education can also increase our confidence in false beliefs——when an educated person thinks he or she has found a pattern, or has made a good-deck/bad-deck judgment, he or she is likely to have confidence in this evaluation...even if it's wrong.

• Is the Iowa Gambling Task really a test of intuition? Researchers made participants take the test while performing another cognitively challenging task. If the Gambling Task required thought (as opposed to intuition) this mentally overtaxed group should've taken longer to catch on. They didn't, implying that cognitive learning and emotion-based learning don't compete for brain space, and that the Iowa Gambling Task requires something other than the traditional idea of conscious thought.

• When gambling for play money, cocaine users significantly underperformed non-users. But when the money got real, cocaine users took more time than non-users, but eventually scored the same.

• Participants with amnesia failed to develop a preference for good decks. This implies that intuition, while somewhat independent of cognition, continues to depend on memory. Our intuition remains built on experience.

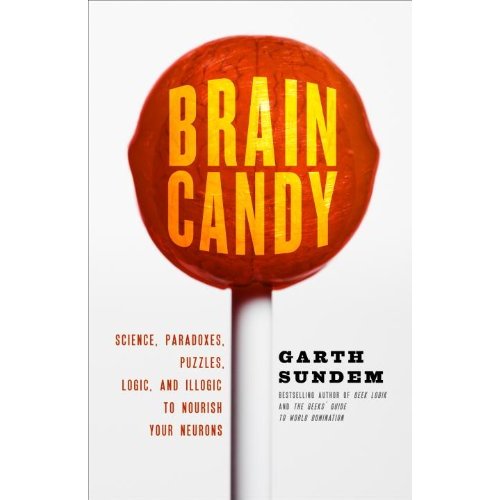

Look at the cover of my new book, Brain Candy. What do you suppose is inside? Use your intuition. Not to check your answers, buy a copy.

Look at the cover of my new book, Brain Candy. What do you suppose is inside? Use your intuition. Not to check your answers, buy a copy.

Comments