By Ersilia Vaudo, translated by Vanessa Di Stefano. If you use this link we get a penny or something.

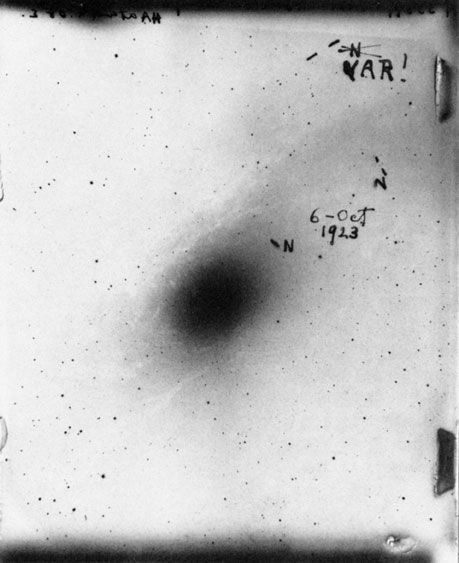

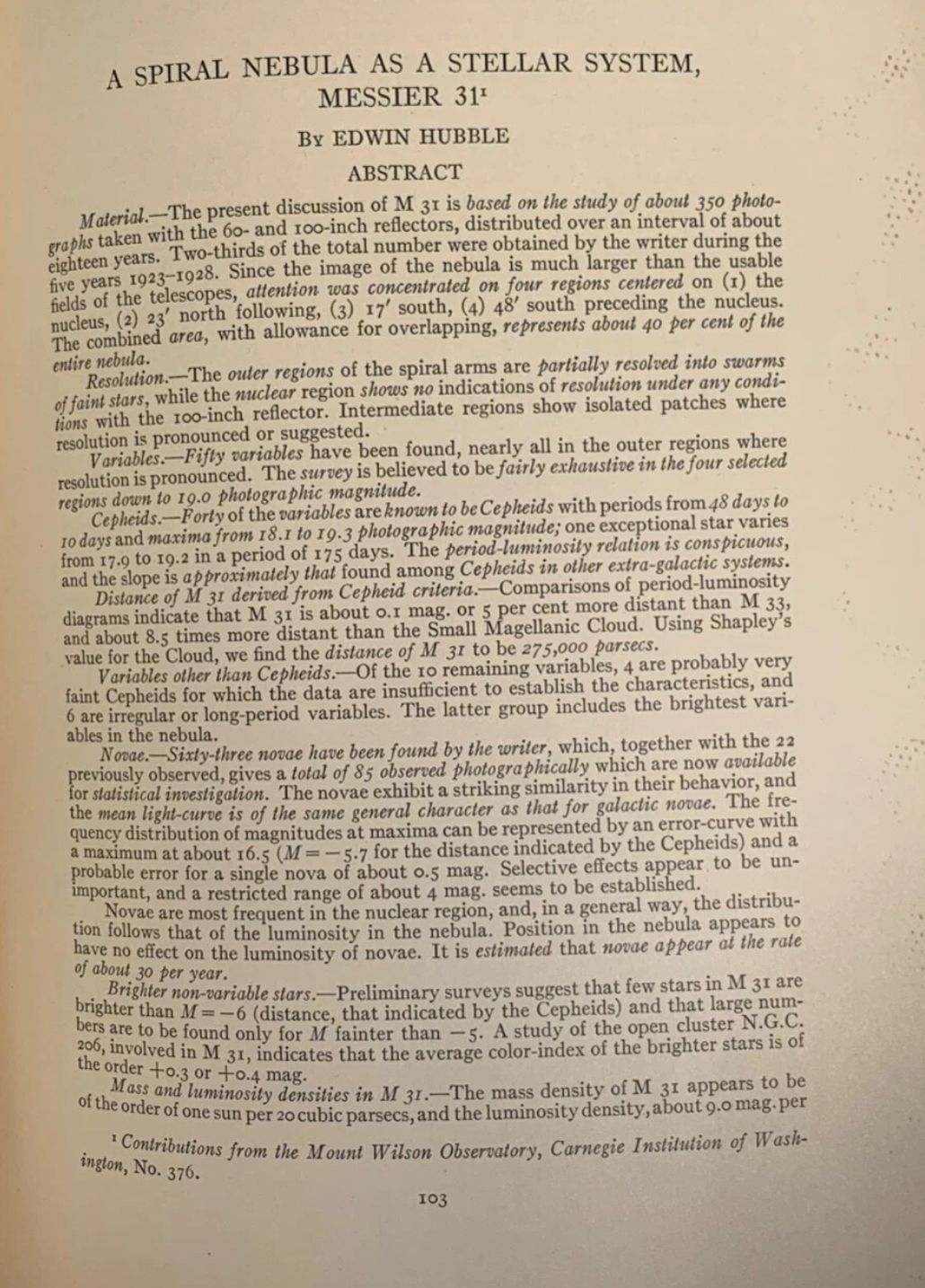

He had published his seminal paper in the March issue of Astrophysical Journal(1) but on April 25th in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences he published the how, and people began to think about what it meant. He had discovered that the collection of gas and dust we call Andromeda was actually another galaxy.

Caption: Hubble showing Cepheid variables on an image of Messier 31

Harlow Shapley, who among others was at the forefront in trying to calculate the size of the universe, had mathematically shown visible spiral nebulae were still part of our galaxy, which meant the Milky Way was still the extent of the universe, a whopping 300,000 light-years in diameter. Hubble wrote him prior to showing his findings and Shapley said upon reading it; “Here is the letter that has destroyed my universe.”

That's what revolutions do.

In the book, you will read about this revolution and four others, and get some idea why we are consumed by exploration.

Our word "desire" comes from the Latin de and sidus - "privation" and "star." Thought symbolically, we are deprived of the stars, and we want to go.(2) That's a terrific way to begin to think about all we've accomplished in astrophysics and why it has consumed so many throughout millennia.

We want to make everything quantifiable, even time. Humans do it across all cultures. But how we perceive time versus how it exists has long been a mystery. Vaudo uses the example of a tribe in the Andes that perceives time as a field in front of them; because they can 'see' the past in their minds. The future is behind them, because it is unknown. Unlike stars, if no one is there to experience it, time ceases to exist.

They're more right than wrong. If Hubble or Webb detects a statistical blip and astronomers infer from it, they're looking at the past. What is happening there now might not be known for hundreds or thousands or billions of years. Because we have only now seen it, that's our expertise. As I sit in my yard reading this book, the sun could've exploded 7 minutes ago and we'd have no way to know we were about to die. If our tool was hearing the past rather than seeing it, we'd be even farther behind reality. If sound could travel through space, nothing would detect the sound of the sun exploding and causing our eventual demise until 13 years after our planet became an icy rock.

Humans instinctively imagine time the way tribes with no writing do - the past in front of us because we see it - and it took a giant brain like Newton to change that perception. He showed that what we were able to perceive could be mathematically reduced. Quantified. Instead of seeing, we could truly predict.

Newton was eventually so successful in changing our perception of the universe that when Einstein came along and said we weren't perceiving it all yet, motion and gravity and therefore time is relative, his work was considered revolutionary.

Gravity is one of the five revolutions and Vaudo covers a lot of ground, you learn something important in every paragraph. No words are wasted. It's comfortably not linear, she may create a waypoint and then bounce off to Kepler doing astrology (hey, he knew ya still gotta pay the bills) and you see why the wandering matters before you are brought back. That's how humans think and it's how we read best.

In 200 brisk pages, you get some surprising cultural touchstones, like T.S. Eliot using poetry to talk about disturbing the universe while astronomers were actually disturbing our universe. It shows how the turn of the 20th century was an exciting time, the scope of the vast expanse was on the mind of everyone, much like if you read pieces from the 1950s and '60s and everyone was talking about human exploration.

Vaudo shows the knowledge that made it possible in just a few decades to go from believing only one galaxy existed to being able look back 200 million years after the Big Bang. Looking back in time.

That's not bad for the tiny image that Voyager 1 sent back in 1990, the one which led Carl Sagan to call us a "pale blue dot." We may be insignificant to the universe, but only if it's devoid of any understanding.

Otherwise, we've accomplished a lot in a short amount of time. Good job, humanity.

And don't deprive yourself of the chance to spend a weekend learning about physics discoveries across time. This is worth your shelf space.

|  |  |  |  |

NOTES:

(1) You will pay a lot for a copy on Ebay today, and rightly so.

(2) Languages don't always make sense. While celerare (speed up) can obviously be opposed by "decelerate" in English and fendere (attack) can be opposed by "defend", "deprivation" is redundant

Comments