Would you really even want to try? People make homemade jam and all-natural weedkillers that are ironically stuffed with chemicals but no one makes their own toaster. It would be among the first things dismissed as unimportant in a post-apocalyptic world.

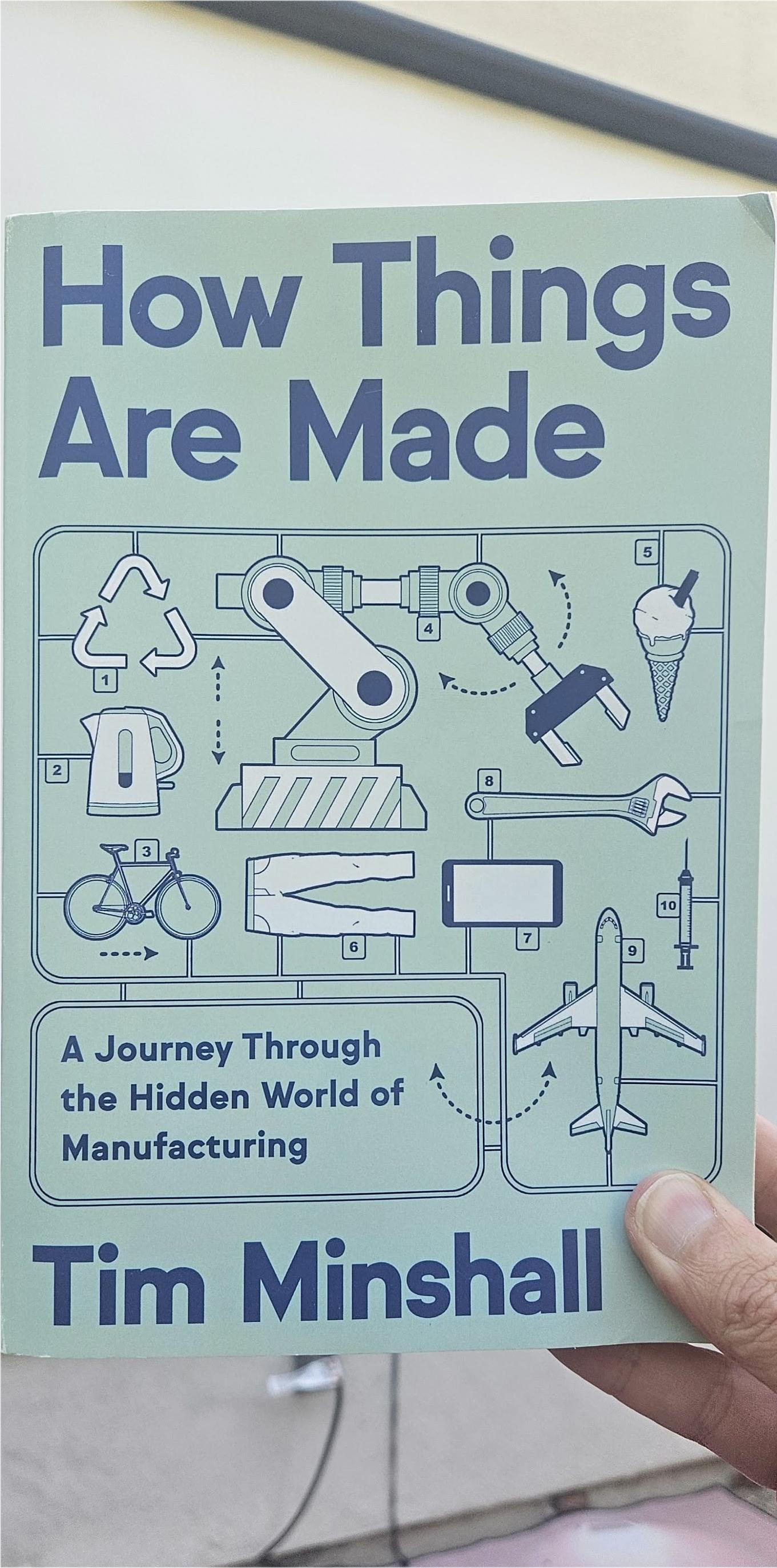

You probably don't think about your toaster but I bet University of Cambridge Professor Tim Minshall, author of How Things Are Made, has annoyed his friends plenty talking about products just like that. And if you are the same way, it is a good book to buy.

If you know about innovation you can infer there are two reasons toast was once only an affectation of the wealthy - 'have the cook bake me delicious, soft bread but then once it is finished, expose it to open flame again and make it hard' - but is now common. The first reason was the high energy cost of cooking in the past. The second reason was difficulty in integration - all the stuff that goes into making the parts for the stuff.

Until the 20th century, toast was a waste of energy but persistent electricity changed all that. Yet commercial electricity had a problem when it first began. Like the first fax machine, no one really needed it. And no one really wanted electricity except at night. You can't just start and stop giant energy engines, Spain learned that this week, and that meant a lot of electricity, and therefore profit, going to waste, which kept costs high and uptake low. So energy companies began to promote new ways to use electricity beyond replacing candles at night.

In the photo of this book (we get a penny or something if you buy it using a link from here) in the background is a 10-ft diameter movie screen, an electrical outlet, which is on a wall, which is on a house, all surrounded by numerous other things. I had nothing to do with the construction of any of those. Instead I am the beneficiary of a very affordable Miracle of Innovation that's really only occurred over the last 200 years. An age of innovation and industrialization that we rarely think about.

With electricity, you could treat yourself like royalty. You could make toast every day.

It's not a coincidence that one of the earliest large manufacturers of American electrified appliances was the same General Electric behind electricity.

The biggest victims of President Trump's retaliatory trade war against tariffs imposed on us by China, Brazil, Europe, etc. are not going to be those who make cars or televisions, we buy so few of those from China it is statistical noise.(1) The companies harmed will be those that make things like toasters. They're cheap and they're easy to manufacture...except they're actually not that easy to manufacture. If you had to build a toaster from scratch it would be a daunting task.

That daunting task is solved by the second thing thing fundamental to taking a product from innovation to commodity.

Integration.

How Things Are Made is a lot more fun than reading my thoughts about toasters and energy policy and the impact of tariffs. Professor Minshall instead discusses politically agnostic stuff like chocolate and toilet paper, things that the 14-year-old in all of us would rather talk about.

That's the beauty of subversively making people a little bit smarter about how the world works in 2025. Without realizing it, you are going to learn about supply chains and vertical intregration but you won't fall asleep doing it, because he keeps it relevant to our lives.

For example, in 1995, I joined a small, unprofitable software company that made physics analysis software. It may seem unfathomable to people now but 30 years ago many scientists and engineers didn't believe you could really get good answers using a computer to do Maxwell's Equations. They knew you could get an answer, but not a good answer.

Though it seemed to be an uphill struggle, within three weeks, I had sold a package to the Coors Brewing Company, a sale just bizarre enough that the academic who had founded the company came over and asked me why they had bought it and how I had sold it so quickly when everyone else said the sales cycle was six months. I told him no one had informed me it took six months to sell, I wanted money now, and since a Coors engineer's name was on a list of people who had expressed interest in our magazine ad I called him and asked him why Coors was worried about electromagnetics. He explained that Coors was in the beer business but they owned everything they could in their entire manufacturing process, which sounded to me a lot like what Henry Ford had done. I had no idea about the breadth of the Coors industrial presence and was intrigued. He was intrigued by my telling him that we could do a lot more than use a computer for calculating coil winding in a motor. He wouldn't have to make things and physically test them each time. I sent him a copy to try and two weeks later he told me it was fantastic and sent us a purchase order.(2)

So my first customer at a complex physics software startup was...a beer company. A beer company that kept prices low by being vertically integrated.

Those hidden tendrils most people don't know exist are actually everywhere and Professor Minshall still sees them the way a very curious outsider would see them.

People like you and me.

Cut to eight years later and we had done an IPO and I was with a group of fellow employees talking about the future of technology and I said something that horrified them. I stated that while ours was an important service business, if you were really going to be someone in America you still had to manufacture something.

We argued the way Gen X men did, over cigars and beer and with a large dose of insults, and I did not convince them that post-industrialization was not just a myth, it was a very bad idea.

Now, nearly everyone believes that post-industrialization is good. After all, farm-to-fork progressives can still get wine from Burgundy while Buy American Conservatives can still have a wide selection at low prices. That's Limosuine Post-Industrialization, not the real thing.

The minute something goes wrong in supply chains, as we saw even in small instances with the COVID-19 pandemic worldwide and baby formula in America, the engine of society will stop. America was lucky. Celebrities and other wealthy people could rush to buy up all of the toilet paper and we have so many trees it only creates a blip for everyone else but the luck was that we never went post-industrial about our food. Farmers are technoligically savvy but they are very much industrial. LEED building mandates and solar power subsidies are the first things lined up against the wall and shot if people don't have food.

In the 'your life is really good, you just may not know it' sense, the book has something for everyone.

For example, Minshall invokes Shumpeters "gale of creative destruction" and eat-the-rich types love the imagery of replacing Ford with electric cars. Meanwhile, conservatives know Tesla was only allowed to succeed because it was allowed to go around government bureaucracy. New car dealers in the U.S. may fly giant American flags and talk about capitalism but they spend millions of dollars per year making sure state laws require you to buy new cars from them - they profit from socialism and preventing creative destruction.(2)

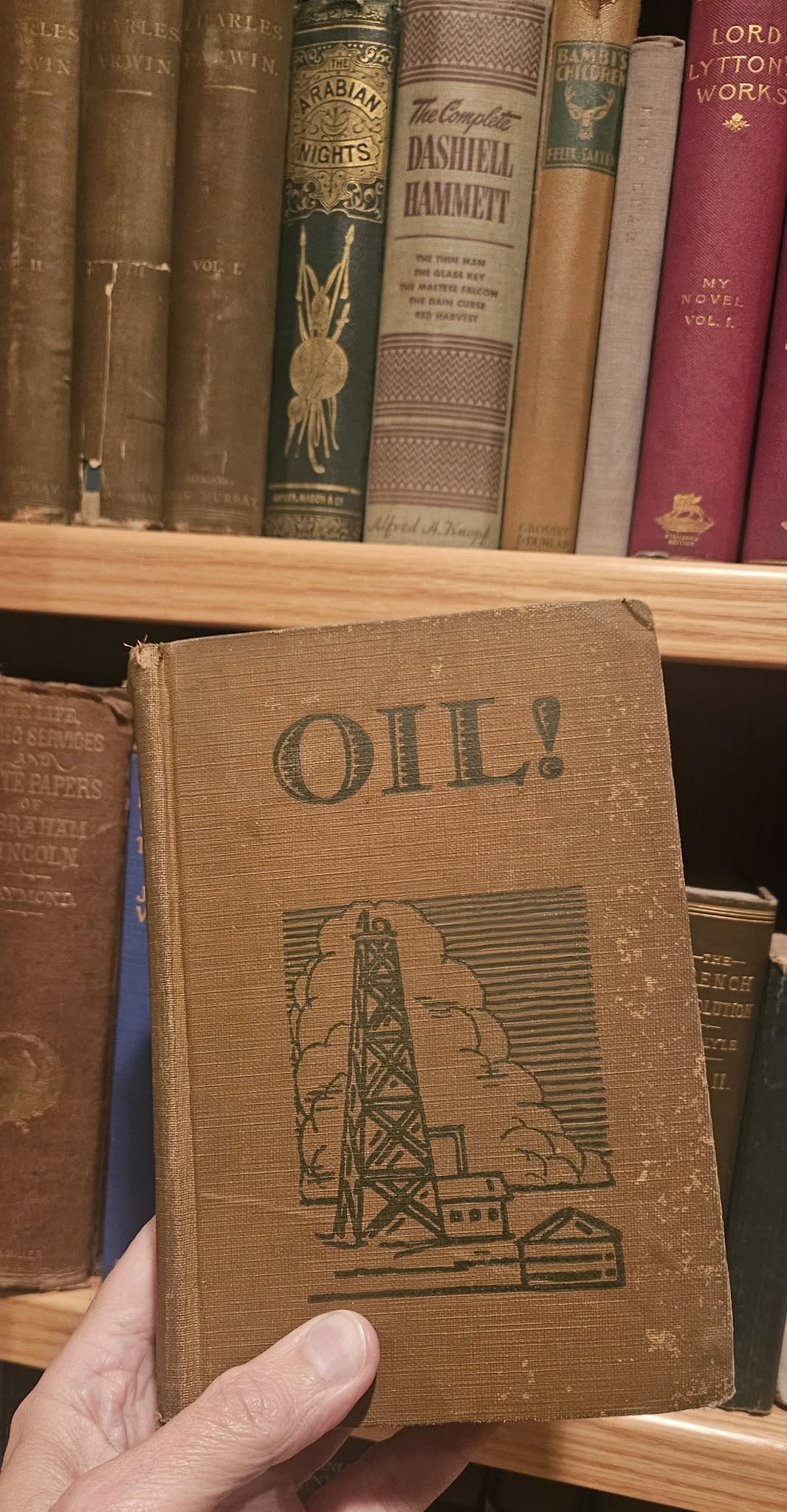

One fun thing about a book like this is also that 100 years from now manufacturing is going to be much different but readers will be able to know a lot of what technology was like in 2025 in a way that they won't get from movies or television. If you read Upton Sinclair's Oil!, for example, you will learn a lot about actual wildcatting 100 years ago even though that technology is only a backdrop for his real goal of socialism and satire.(3)

This book provides the same insights about the manufacturing processes that exist today.

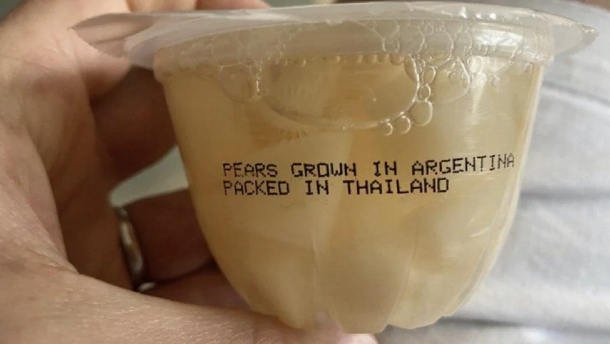

Those processes will be much different in the future, perhaps ours will be unrecognizable to them, but a lot of the logic behind growing pears in Argentina to pack them in Thailand to sell them in South America makes perfect sense when you understand the world as it exists today, and how a place that grows food well but can only ship at high environmental cost is a win for us all if they let someone else who has integration and supply-chain infrastructure handle that part.

The book can help you and understand that now, plus offer insight on how we're approaching a tipping point where we might want to be less post-industrial, and for future readers it may be a fun way to look back in time and see how things were.

Until then, you can read it just to better appreciate modern toilet paper.

|  |  |  |  |

NOTES:

(1) It won't be the public. No one really needs a new toaster at this point. In my Facebook Buy Nothing group, people give one away every two weeks.

(2) Progessives in California were the top customers of Tesla, the state gave the company a billion-dollar subsidy. They felt like mavericks sticking it to Big Auto because they didn't have to buy from a dealer. Meanwhile, FedEx was prevented by law from delivering anything except premium packages, even though they could more affordably deliver "first class" mail to our homes than the US Postal Service, and without the $125 billion dollars in unfunded liabilities that the USPS now carries. They are still prevented from doing so. No creative destruction allowed.

(3) The film version, "There Will Be Blood", basically ignores that and therefore has no anthropogolical value. It's just a movie.

Comments