Unzicker offers a gloomy panoramic view of the decline of physics over recent decades, suggesting that the root of this evil comes from the Americanization of science after World War II. One of the critical aspects of the question is the lack of philosophical culture in the US in comparison with Europe and its scientific tradition, which, according to the author, has quickly spread to the rest of the world. I have more or less the same idea, not only regarding science but also culture in general. Indeed, I have divided the books in the small library in my house into those published before 1945 (which I call “classical”) and those published after 1945. Certainly, I agree that the world has changed significantly since the end of World War II, as Western countries became dominated by American pragmatic values (business as usual) and important theoretical fundamental questions were neglected. Science in particular, especially physics, abandoned the big intellectual challenges and became an industry coupled with the economy, with most discoveries associated with large financial investments in technology.

It is quite true that, as said by Unzicker, science today has abandoned or left in minority the work of individual thinkers and has rendered into big enterprises of massive collaborations. His sentence “American belief that with money, power, and technology, anything could be accomplished,” deserves to be put in a frame. Can intelligence in science be substituted by economic investment?

Unzicker makes several remarkable historical observations, such as that about the similarity between ancient Rome and present-day US empires. He might be right that the US will be remembered for its military power, like Rome, rather than its intellectual abstractions, like Greece, the cradle of Western philosophy. There is a general resonance throughout the book of nostalgia for the times when Germany led scientific research in physics. This reminds me of a recent book (a colossal book with 4800 pages) published in 2020 by Tod H. Rider titled Forgotten Creators. How German-Speaking Scientists and Engineers Invented the Modern World, And What We Can Learn From Them. This book explains the difference between the German and American ways of doing science and why science has been in decline since Americans became leaders of scientific production.

Nonetheless, I would say that the reasons for this change in our civilization, the reasons for the end of classical European values, go beyond the North American hegemony. It is not America’s fault that it dominates the world. Rather, America’s status is due to the weakness of Europe, the power and global influence of which has already been decreasing for a century. Germany, in particular (the home country of Unzicker and visionary Oswald Spengler, who a century ago was the author of The Decline of the West), is now contemplating how the US government is peeing on its gates, with its possible implication in the casus belli sabotage of Nord stream pipelines, among other facts. Germany now must accept these acts and behave submissively because it lacks power. I understand Unzicker’s resentment towards the US.

His Kulturpessimismus is exemplified in: “We are already far advanced in our understanding of nature; admittedly the standard models are not perfect, but the next experiments will certainly provide clues to a more fundamental theory. In short: Give us more money and we will find something that we will somehow interpret and celebrate as a confirmation of our standard models. Or we might find nothing at all, which would be even more awesome, because it points to physics ‘beyond’ these models (This is not a parody. In 2013, the Nobel Prize was awarded for a confirmation of the Standard Model; in 2015, the discovery of a deviation from it was considered worthy of the prize) That narrative is thoroughly mendacious. It should go something like: We have no idea; we are aware that we are not predicting anything, and we feel quite clearly that we are at a dead end. But before you pull the plug on our funding, we will throw a lot of dust in your eyes. This is where fundamental research stands” (Ch. 14).

The author makes valuable observations in comparing companies in capitalist markets with the present-day production of theories of physics or efforts to save them when they are “too big to fail.” I find this observation eye-opening. He refers mainly to the development of ideas within particle physics and its standard model, but I think this is happening to some degree to some of the fundamental ideas of whatever is meant by “standard theory.” For instance, although not mentioned by Unzicker, I see the standard model of cosmology has a similar status as the standard model of physics and that the number of problems is no lower. Some of us astrophysicists and cosmologists believe that the fundamental ideas of a standard model of ΛCDM are unbearable; however, it keeps its position despite the continuous reverberation of the expression “crisis in cosmology.” It is too big to fail: accepting that the big bang theory is wrong would mean thousands of jobs would be lost and would result in a total lack of credibility of astrophysics among the general public. Thus, the specific problem with the standard model does not matter, as we always hear strong voices say, “We have to save the standard model.” This is similar to the case of the economic crisis of 2008 when strong voices in the US and Europe claimed that they had to save the big banks, whatever the cost. The failure of such a fundamental pillar of our understanding of physics or astronomy might lead to the collapse of the whole system of the financing of fundamental physics, as could happen in the distant future, but the temporary support delays such a paradigm shift for as long as possible.

In my opinion, the author may be focusing too much on particle physics, which has certainly been an integral part of fundamental research in physics in the last century, but it does not represent the entire field of physics. Apart from applied physics (and astrophysics, which are touched upon in a very superficial manner), there are other fields of research within fundamental physics. Although these fields may have less of an impact in mass media, they have possibly produced more successful results in recent decades.

Towards the middle of the book, a set of aggressive critiques are given to the works on quantum chromodynamics, supersymmetry, string theory, and so on provided by most of the greatest names (both North American and not) in physics over the last 80 years, including Feynman, Gell-Mann, and Weinberg. In my opinion, Unzicker gets into trouble by discussing too many details about physical theories. He dares to criticize almost everything that has been done in particle physics and quantum mechanics during the period in question. Some of his points might be right, but the enterprise of trying to critically understand all the major advances in physics in recent decades exceeds the capacity of a single researcher (especially one who is not doing research professionally). There is a tone of amateurism here.

Unzicker, however, cites as heroes of modern physics characters like Pierre-Marie Robitaille, a radiologist in a US hospital who has never worked as a professional researcher in astrophysics and has never published a paper in a serious professional physics or astronomy journal. He uses to publish in Physics Essays and Progress in Physics, which were not even on the list of 1200 journals of physics and astronomy with a measured SJR index in 2021 (for the first journal, the last SJR index was given in 2019: 0.111, which is equivalent to the very end of the fourth quartile; and the second journal is not registered in SJR). Nevertheless, Robitaille dared to posit new revolutionary ideas about, for example, stellar astrophysics, black holes, and cosmic microwave background radiation (he is famous for having paid The New York Times US$100,000 to publish a page with his crackpot theory on this topic). If we are to believe that the hope of physics in the future lies with this kind of researcher, we will be left with an even more pessimistic impression about physics and its future.

Unzicker argues that leaving physics in the hands of specialists is like leaving religion in the hands of a few priests. I disagree with that point of view. Specialists might behave like a herd and engage in groupthink, but their knowledge is necessary to enter discussions in the field. It is highly unlikely that a new Einstein working in a patent office will produce something revolutionary in physics today, not only because of the peer-review system of journals but also due to the current structure of knowledge.

Outsiders cannot play the game anymore—or at least I do not know of any exception to this rule among many tens or hundreds of amateur researchers that I have known. The problem with these amateurs with delusions of grandeur is that when they want to enter a new field of research through a grand gate rather than a small humble door. They should first learn about the field, publishing 5-10 papers on normal (non-revolutionary) physics before doing something “great.”

Unzicker presents a circular argument: new researchers do not publish in important journals because orthodox science closes the doors to new ideas. Of course, without having a Ph.D. on a topic and without having published a single paper in the field (in a journal with a good reputation), if you want to enter a new field of research by proposing an idea that refutes well-established ideas, you will most likely be rejected and considered a “crackpot.” However, the point is not that these revolutionary ideas are rejected (which may happen even to professional researchers and experts in a field) but that amateur researchers do not make the effort to publish papers of normal (non-revolutionary) science in normal journals of physics to demonstrate their competence in the field.

In many parts of his book, Unzicker mentions that vital problems in physics (first noted in the 1930s or previously) remain to be solved and that we should make physics great again by returning to previous European values. I doubt this is possible. Physics has given most of what it can give regarding the main understanding of nature. Now, only small details or exotic speculations remain to be explored. Unzicker does not want to hear that “the simple things have all been discovered.” He prefers to think of a romantic science of individual geniuses as a model to be preferred to the corporative consensus of big science as the solution for future physics. I agree that important ideas can only be produced by individual scientists, but I doubt we will see times in which the science of individual geniuses—outsiders of official research corporations tackling important questions of fundamental physics—will flourish again, as happened in Europe for the four centuries before World War II.

In my opinion, these glorious times of the physics of the first decades of the 20th century will not return (at least not during the present cycle of our civilization, though maybe it will happen in the distant future in another civilization). We have to accept that the golden era of scientific discoveries has passed, regardless of whether America or China governs the Earth and distributes funds for producing scientific works (Unzicker talks about this question in his last chapter). The time of great fundamental physics is over.

Physicist Per Bak (1948-2002) said in an interview that “most particle physicists think they’re still doing science when they are really cleaning up the mess after the party.” I think Unzicker would agree with this statement. If we follow the logic of this discourse, there is now only one place for working out minor details or keeping the illusion of being close to discovering something great (non-baryonic dark matter, for instance), a discovery that never comes to fruition but serves to apply more funds and keep the industry going.

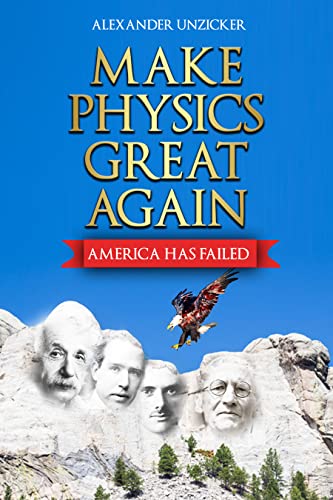

Unzicker’s hope is to “Make Physics Great Again,” mimicking the discourse of Donald Trump (replacing the word “America” with “Physics”). However, I cannot see a future in which America or physics will be the same as they were in the past. Sooner or later, perhaps we should realize that science was great in the past but that we should now dedicate our intellectual efforts to other activities if we want to do something “great.” Today, scientific developments are for technicians and nerds, not for intellectuals or philosophers as in the past.

Comments