In the 1980s, the discovery of soccer-ball-shaped carbon molecules called buckyballs helped to spur an explosion in nanotechnology research.

Now, there appears to be a new ball on the pitch - a cluster of 40 boron atoms forms a hollow molecular cage similar to a carbon buckyball. It's the first experimental evidence that a boron cage structure, previously only a matter of speculation, does indeed exist.

Carbon buckyballs are made of 60 carbon atoms arranged in pentagons and hexagons to form a sphere—like a soccer ball. Their discovery in 1985 was soon followed by discoveries of other hollow carbon structures including carbon nanotubes. Another famous carbon nanomaterial—a one-atom-thick sheet called graphene—followed shortly after.

After buckyballs, scientists wondered if other elements might form these odd hollow structures. One candidate was boron, carbon's neighbor on the periodic table. But because boron has one less electron than carbon, it can't form the same 60-atom structure found in the buckyball. The missing electrons would cause the cluster to collapse on itself. If a boron cage existed, it would have to have a different number of atoms.

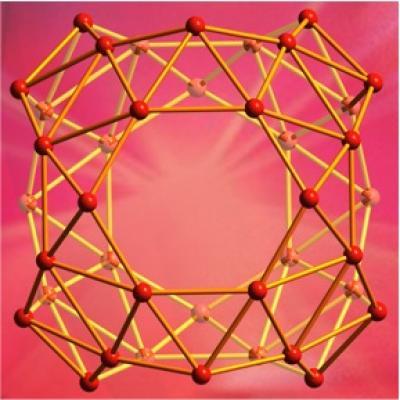

Borospherene: Researchers have shown that clusters of 40 boron atoms form a molecular cage similar to the carbon buckyball. This is the first experimental evidence that such a boron cage structure exists. Credit: Wang lab / Brown University

"This is the first time that a boron cage has been observed experimentally," said Lai-Sheng Wang, a professor of chemistry at Brown University who led the team that made the discovery. "As a chemist, finding new molecules and structures is always exciting. The fact that boron has the capacity to form this kind of structure is very interesting."

Wang and his colleagues describe the molecule, which they've dubbed borospherene, in Nature Chemistry.

Wang and his research group have been studying boron chemistry for years. In a paper published earlier this year, Wang and his colleagues showed that clusters of 36 boron atoms form one-atom-thick disks, which might be stitched together to form an analog to graphene, dubbed borophene. Wang's preliminary work suggested that there was also something special about boron clusters with 40 atoms. They seemed to be abnormally stable compared to other boron clusters. Figuring out what that 40-atom cluster actually looks like required a combination of experimental work and modeling using high-powered supercomputers.

On the computer, Wang's colleagues modeled over 10,000 possible arrangements of 40 boron atoms bonded to each other. The computer simulations estimate not only the shapes of the structures, but also estimate the electron binding energy for each structure—a measure of how tightly a molecule holds its electrons. The spectrum of binding energies serves as a unique fingerprint of each potential structure.

The next step is to test the actual binding energies of boron clusters in the lab to see if they match any of the theoretical structures generated by the computer. To do that, Wang and his colleagues used a technique called photoelectron spectroscopy.

Chunks of bulk boron are zapped with a laser to create vapor of boron atoms. A jet of helium then freezes the vapor into tiny clusters of atoms. The clusters of 40 atoms were isolated by weight then zapped with a second laser, which knocks an electron out of the cluster. The ejected electron flies down a long tube Wang calls his "electron racetrack." The speed at which the electrons fly down the racetrack is used to determine the cluster's electron binding energy spectrum—its structural fingerprint.

The experiments showed that 40-atom-clusters form two structures with distinct binding spectra. Those spectra turned out to be a dead-on match with the spectra for two structures generated by the computer models. One was a semi-flat molecule and the other was the buckyball-like spherical cage.

"The experimental sighting of a binding spectrum that matched our models was of paramount importance," Wang said. "The experiment gives us these very specific signatures, and those signatures fit our models."

The borospherene molecule isn't quite as spherical as its carbon cousin. Rather than a series of five- and six-membered rings formed by carbon, borospherene consists of 48 triangles, four seven-sided rings and two six-membered rings. Several atoms stick out a bit from the others, making the surface of borospherene somewhat less smooth than a buckyball.

As for possible uses for borospherene, it's a little too early to tell, Wang says. One possibility, he points out, could be hydrogen storage. Because of the electron deficiency of boron, borospherene would likely bond well with hydrogen. So tiny boron cages could serve as safe houses for hydrogen molecules.

But for now, Wang is enjoying the discovery.

"For us, just to be the first to have observed this, that's a pretty big deal," Wang said. "Of course if it turns out to be useful that would be great, but we don't know yet. Hopefully this initial finding will stimulate further interest in boron clusters and new ideas to synthesize them in bulk quantities."

Comments