As much as 47 percent of the edible U.S. seafood supply is lost each year, mainly from consumer waste, according to a paper in Global Environmental Change, which takes advantage of a recent spotlight on the sustainability of the world's seafood resources.

The 2010 U.S. Dietary Guidelines recommended increasing seafood consumption to eight ounces per person per week and consuming a variety of seafood in place of some meat and poultry. Yet achieving those levels would require doubling the U.S. seafood supply, which could threaten the global seafood supply if more farming and less waste are not considered.

"If we're told to eat significantly more seafood but the supply is severely threatened, it is critical and urgent to reduce waste of seafood," says study leader David Love, PhD, a researcher with the Public Health and Sustainable Aquaculture project at the CLF and an assistant scientist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future

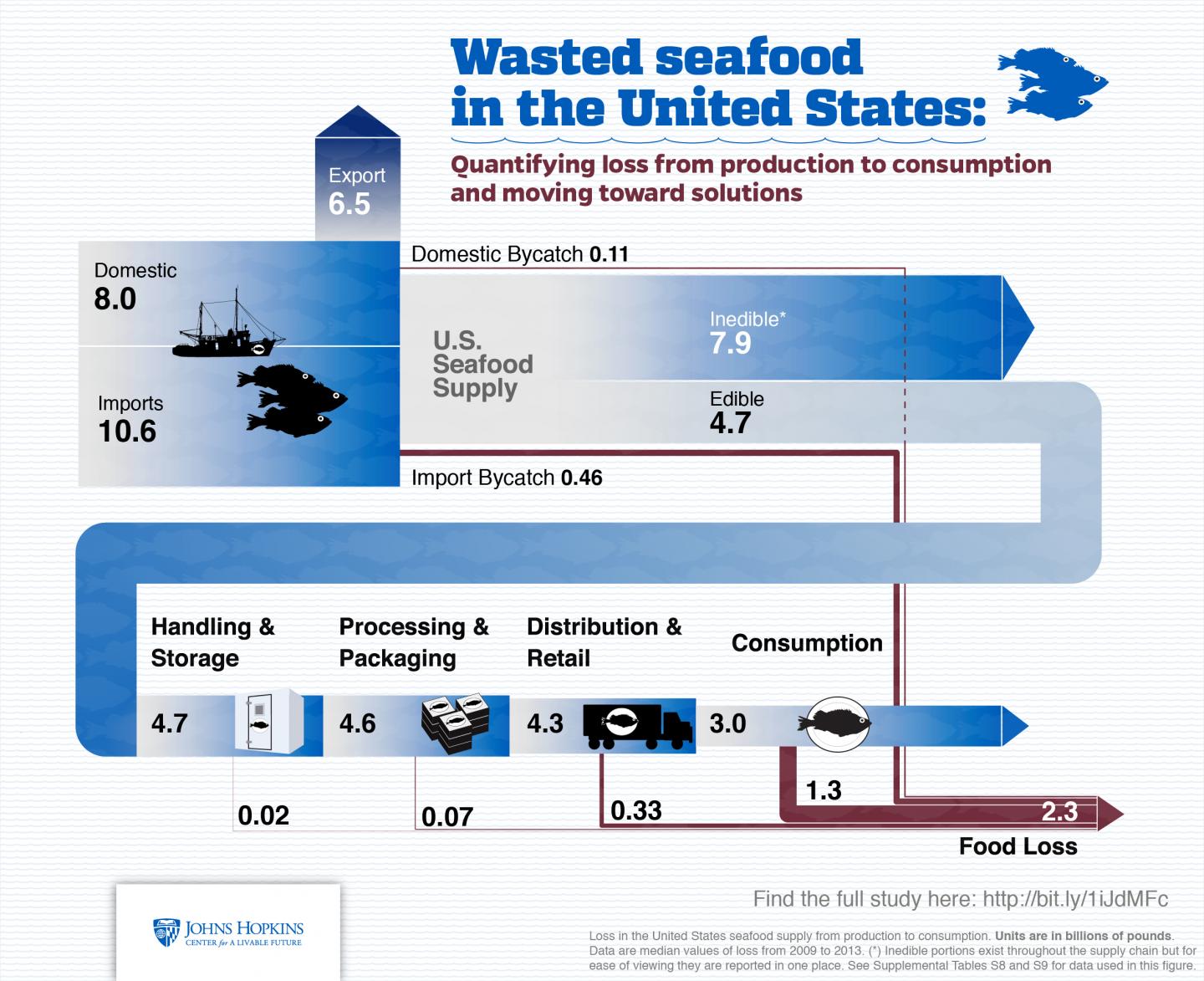

The new study focused on the amount of seafood lost annually at each stage of the food supply chain and at the consumer level. After compiling data, the researchers estimated the U.S. edible seafood supply at approximately 4.7 billion pounds per year, which includes domestic and imported products minus any exported products. Some of the edible seafood supply is wasted as it moves through the supply chain from hook or net to plate. They found that the amount wasted each year is roughly 2.3 billion pounds.

Of that waste, they say that 330 million pounds are lost in distribution and retail and 573 million pounds are lost to bycatch but the vast majority, 1.3 billion pounds, are lost at the consumer level. As your mother told you, seafood doesn't do well as leftovers.

The researchers found the greatest portion of seafood loss occurred at the level of consumers (51 to 63 percent of waste). Sixteen to 32 percent of waste is due to bycatch, while 13 to 16 percent is lost in distribution and retail operations. To illustrate the magnitude of the loss, the authors estimate this lost seafood could contain enough protein to fulfill the annual requirements for as many as 10 million men or 12 million women; and there is enough seafood lost to close 36 percent of the gap between current seafood consumption and the levels recommended by the 2010 U.S. Dietary Guidelines.

Waste reduction has the potential to support increased seafood consumption without further stressing aquatic resources, says Roni Neff, PhD, director of the Food System Sustainability&Public Health Program at CLF and an assistant professor with the Bloomberg School of Public Health. She says that while a portion of the loss could be recovered for human consumption, "we do not intend to suggest that all of it could or should become food for humans."

The researchers offer several approaches to reduce seafood waste along the food chain from catch to consumer. Suggestions range from packaging seafood into smaller portion sizes at the processing level to encouraging consumer purchases of frozen seafood. Some loss is unavoidable, but the researchers hope these estimates and suggestions will help stimulate dialogue about the significance and magnitude of seafood loss.

Comments