Almost 20 percent of the Earth's atmosphere is oxygen. Green plants produce it as a byproduct of photosynthesis and it, in turn, is used by most living things on the planet to keep our metabolisms running.

Yet before those photosynthesizing organisms appeared about 2.4 billion years ago, the atmosphere was mostly carbon dioxide, a lot like Mars and Venus.

The common hypothesis is that there must have been a small amount of oxygen in the early atmosphere. Where did this abiotic ("non-life") oxygen come from? Oxygen reacts quite aggressively with other compounds, so it would not persist for long without some continuous source.

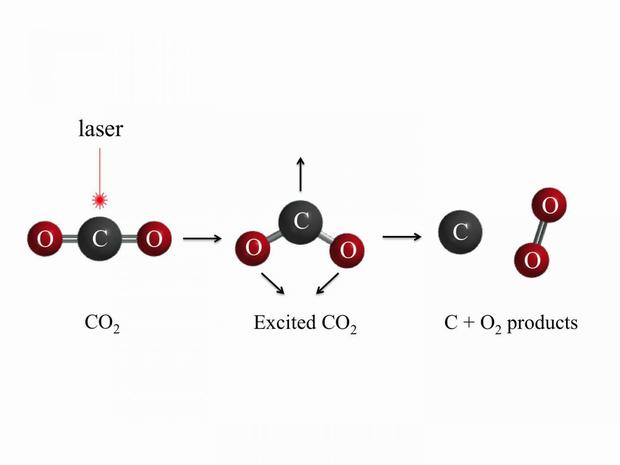

Scholars from UC Davis have shown that oxygen can be formed in one step by using a high energy vacuum ultraviolet laser to excite carbon dioxide.

Carbon dioxide can be split by vacuum ultraviolet laser to create oxygen in one step. The discovery may change how we think about the evolution of atmospheres. Credit: Zhou Lu, UC Davis

"Previously, people believed that the abiotic (no green plants involved) source of molecular oxygen is by CO2 + solar light — > CO + O, then O + O + M — > O2 + M (where M represents a third body carrying off the energy released in forming the oxygen bond)," UC Davis graduate student Zhou Lu said in their statement. "Our results indicate that O2 can be formed by carbon dioxide dissociation in a one step process. The same process can be applied in other carbon dioxide dominated atmospheres such as Mars and Venus."

Zhou used a vacuum ultraviolet laser to irradiate CO2 in the laboratory. Vacuum ultraviolet light is so-called because it has a wavelength below 200 nanometers and is typically absorbed by air. The experiments were performed by using a unique ion imaging apparatus developed at UC Davis.

Such one-step oxygen formation could be happening now as carbon dioxide increases in the region of the upper atmosphere, where high energy vacuum ultraviolet light from the Sun hits Earth or other planets. It is the first time that such a reaction has been shown in the laboratory. According to one of the scientists who reviewed the paper for Science, Zhou's work means that models of the evolution of planetary atmospheres will now have to be adjusted to take this into account.

Comments