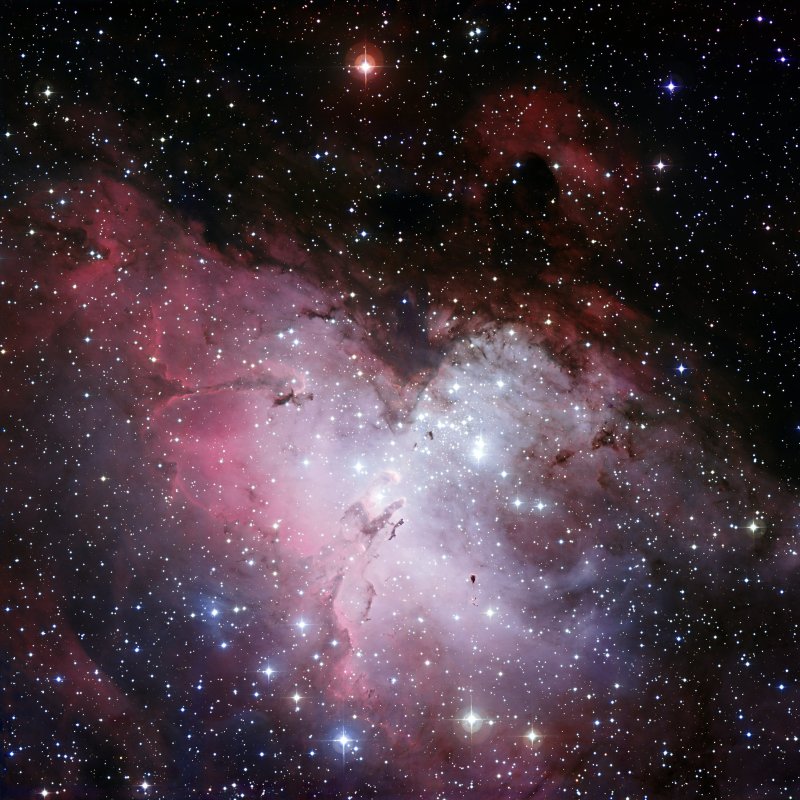

The powerful light and strong winds from these massive new arrivals are shaping light-year long pillars, seen in the image partly silhouetted against the bright background of the nebula. The nebula itself has a shape vaguely reminiscent of an eagle, with the central pillars being the "talons".

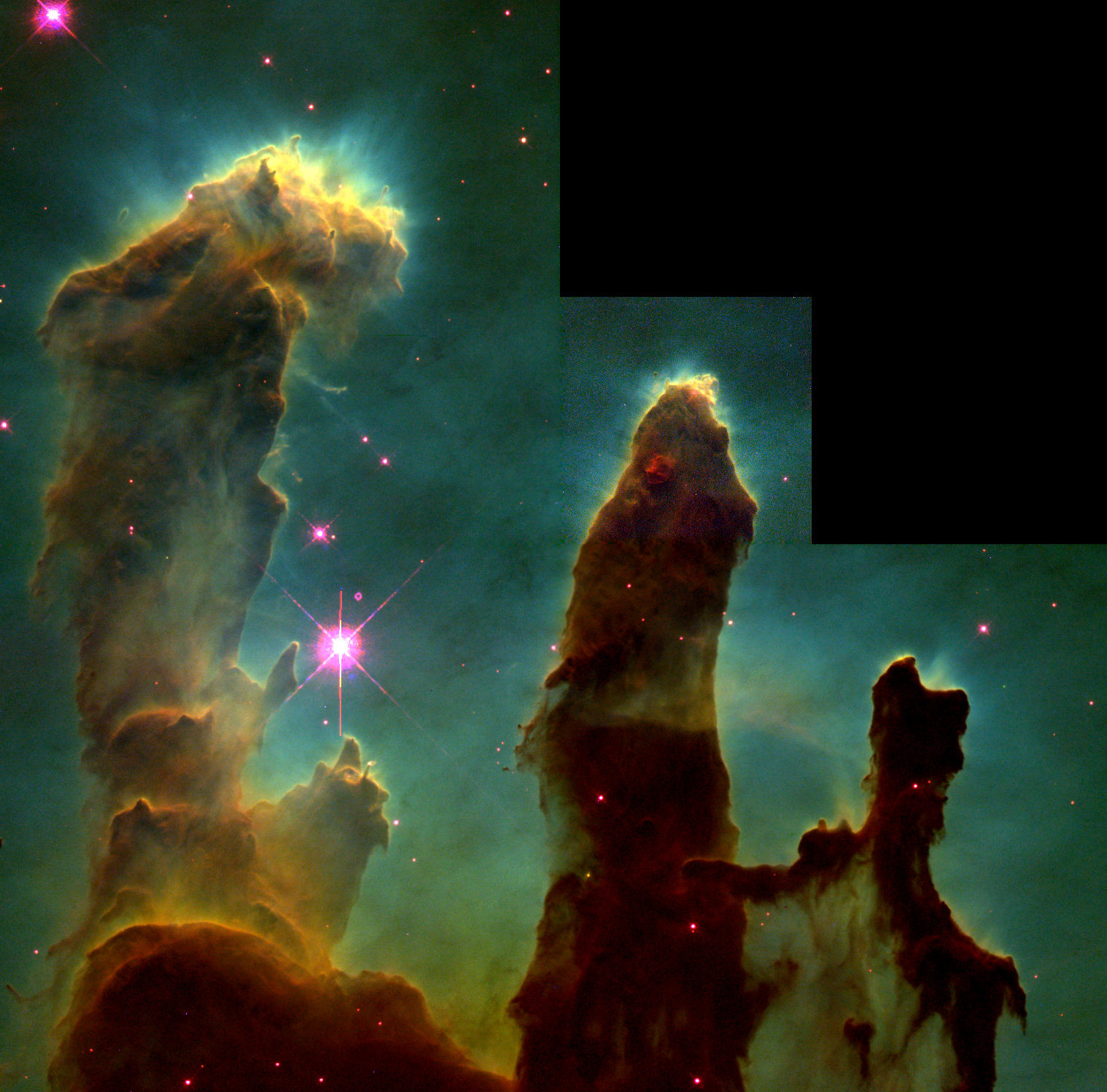

The Eagle Nebula was discovered by the Swiss astronomer, Jean Philippe Loys de Chéseaux, in 1745�nd found again twenty years later by the French comet hunter, Charles Messier, who included it as number 16 in his famous catalogue, and remarked that the stars were surrounded by a faint glow. The Eagle Nebula achieved iconic status in 1995, when its central pillars were depicted in the famous image below obtained with the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope.

The Pillars of Creation. These eerie, dark pillar-like structures are actually columns of cool interstellar hydrogen gas and dust that are also incubators for new stars. The pillars protrude from the interior wall of a dark molecular cloud like stalagmites from the floor of a cavern. Credit: Jeff Hester and Paul Scowen (Arizona State University), and NASA/ESA

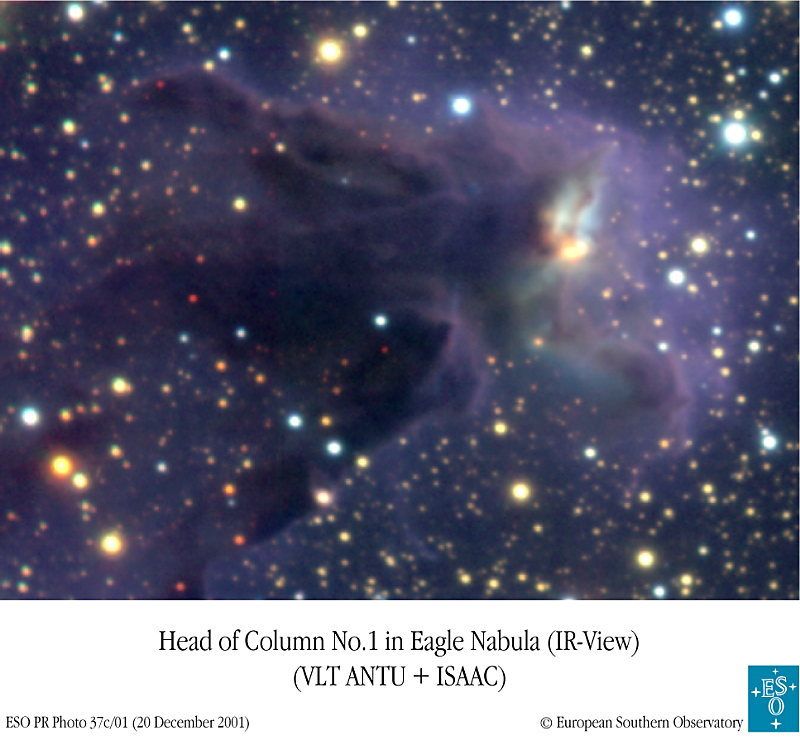

In 2001, ESO's Very Large Telescope (VLT) captured another breathtaking image of the nebula , in the near-infrared, giving astronomers a penetrating view through the obscuring dust, and clearly showing stars being formed in the pillars.

An enlarged view of the head of the largest of the three main pillars, Column 1. The head is almost transparent around the edges at near-infrared wavelengths, but there is still a substantial opaque core which even these near-infrared VLT observations cannot penetrate. The complex blueish nebulosity bisected by a dark lane near the tip is being lit up by the bright yellow star just below it, which appears to be very young and rather massive. Several of the much fainter stars to the right of and below this source are found to be associated with EGGs seen in the Hubble image, and these all have much lower masses. Finally, there is a faint streak of blue light emanating from from the tip of EGG 23, one of the darkest parts of Column 1, ending in a blue blob further north. An equal distance to the south of the EGG and off the head, there is another curving blue nebulosity. These features are also seen in the Hubble image, and may be part of a Herbig-Haro jet coming from a young star buried deeply in EGG 23 and invisible in this image. Credit ESO

A newly released image, obtained with the Wide-Field Imager camera attached to the MPG/ESO 2.2-metre telescope at La Silla, Chile, covers an area on the sky as large as the full Moon, and is about 15 times more extensive than the previous VLT image, and more than 200 times more extensive than the iconic Hubble visible-light image. The whole region around the pillars can now be seen in exquisite detail.

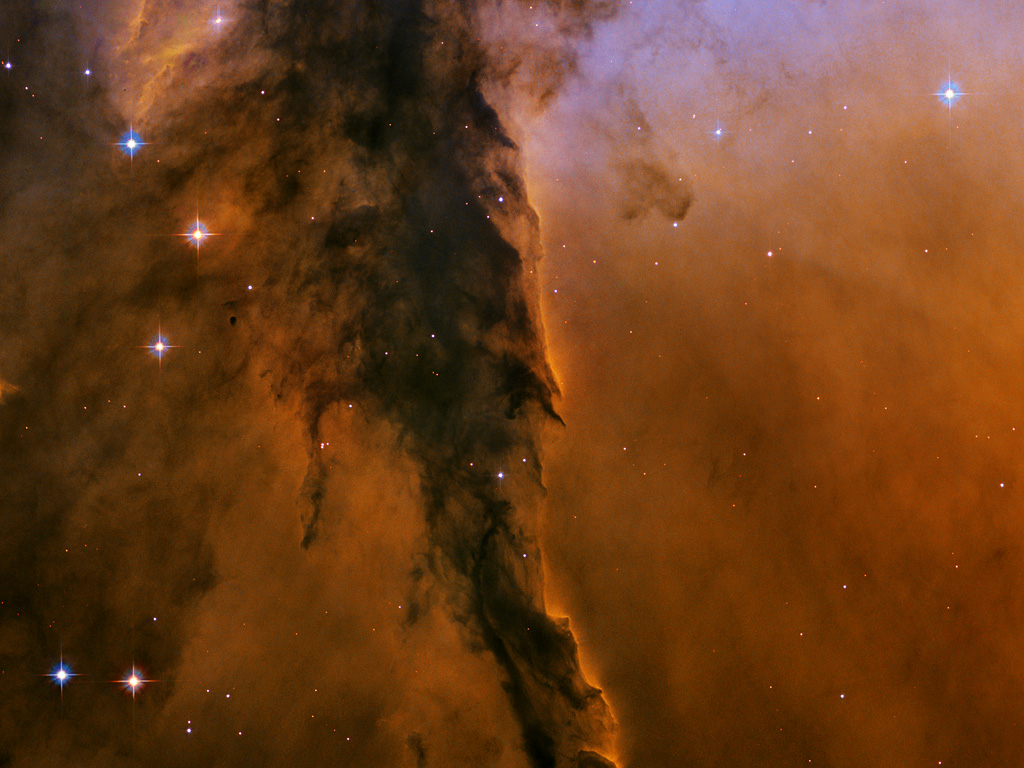

Credit: NASA, ESA, and The Hubble Heritage Team STScI/AURA)

Appearing like a winged fairy-tale creature poised on a pedestal, the soaring tower is 9.5 light-years or about 90 trillion kilometres high, about twice the distance from our Sun to the next nearest star.

Stars in the Eagle Nebula are born in clouds of cold hydrogen gas that reside in chaotic neighbourhoods, where energy from young stars sculpts fantasy-like landscapes in the gas. The tower may be a giant incubator for those newborn stars. A torrent of ultraviolet light from a band of massive, hot, young stars [off the top of the image] is eroding the pillar.

The starlight also is responsible for illuminating the tower's rough surface. Ghostly streamers of gas can be seen boiling off this surface, creating the haze around the structure and highlighting its three-dimensional shape. The column is silhouetted against the background glow of more distant gas.

The edge of the dark hydrogen cloud at the top of the tower is resisting erosion, in a manner similar to that of brush among a field of prairie grass that is being swept up by fire. The fire quickly burns the grass but slows down when it encounters the dense brush. In this celestial case, thick clouds of hydrogen gas and dust have survived longer than their surroundings in the face of a blast of ultraviolet light from the hot, young stars.

Inside the gaseous tower, stars may be forming. Some of those stars may have been created by dense gas collapsing under gravity. Other stars may be forming due to pressure from gas that has been heated by the neighbouring hot stars.

The first wave of stars may have started forming before the massive star cluster began venting its scorching light. The star birth may have begun when denser regions of cold gas within the tower started collapsing under their own weight to make stars.

The bumps and fingers of material in the centre of the tower are examples of these stellar birthing areas. These regions may look small but they are roughly the size of our solar system. The fledgling stars continued to grow as they fed off the surrounding gas cloud. They abruptly stopped growing when light from the star cluster uncovered their gaseous cradles, separating them from their gas supply.

Ironically, the young cluster's intense starlight may be inducing star formation in some regions of the tower. Examples can be seen in the large, glowing clumps and finger-shaped protrusions at the top of the structure. The stars may be heating the gas at the top of the tower and creating a shock front, as seen by the bright rim of material tracing the edge of the nebula at top, left. As the heated gas expands, it acts like a battering ram, pushing against the darker cold gas. The intense pressure compresses the gas, making it easier for stars to form. This scenario may continue as the shock front moves slowly down the tower.

The dominant colours in the image were produced by gas energized by the star cluster's powerful ultraviolet light. The blue colour at the top is from glowing oxygen. The red colon in the lower region is from glowing hydrogen. The Eagle Nebula image was taken in November 2004 with the Advanced Camera for Surveys aboard the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope.

Three-colour composite mosaic image of the Eagle Nebula (Messier 16), based on images obtained with the Wide-Field Imager camera on the MPG/ESO 2.2-metre telescope at the La Silla Observatory. At the centre, the so-called “Pillars of Creation” can be seen. This wide-field infrared image shows not only the central pillars, but also several others in the same star-forming region, as well as a huge number of stars in front of, in, or behind the Eagle Nebula. The cluster of bright stars to the upper right is NGC 6611, home to the massive and hot stars that illuminate the pillars. The “Spire” — another large pillar — is in the middle left of the image. Credit: ESO

The "Pillars of Creation" are in the middle of the image, with the cluster of young stars, NGC 6611, lying above and to the right. The "Spire" — another pillar captured by Hubble — is at the centre left of the image.

Finger-like features protrude from the vast cloud wall of cold gas and dust, not unlike stalagmites rising from the floor of a cave. Inside the pillars, the gas is dense enough to collapse under its own weight, forming young stars. These light-year long columns of gas and dust are being simultaneously sculpted, illuminated and destroyed by the intense ultraviolet light from massive stars in NGC 6611, the adjacent young stellar cluster. Within a few million years — a mere blink of the universal eye — they will be gone forever.

Comments